AustLit

-

Spinoza’s monism is strikingly different. His metaphysics supposes a single substance, which encompasses and comprises all of nature.

This substance is God:

“By God, I mean a being absolutely infinite — that is, a substance consisting in infinite attributes, of which each expresses eternal and infinite essentiality.” (Spinoza, 1883 — Part I, Def. VI)

The Dutch philosopher rejects the idea of an intentionally willing, anthropomorphic God (Tiebout, 1956, p.512), arguing instead that “From the necessity of the divine nature must follow an infinite number of things in infinite ways” (Spinoza, 1883 — Part I, Prop. XVI). Accordingly, Spinoza’s modes are particular expressions of attributes — humans can only access the attributes of thought and extension — and these are particular ways of conceiving the essence of nature or substance (Spinoza, 1883 — Part I, Def. IV & Def. V). For instance, a physical teapot would be a mode known through the attribute of extension. Ergo, Spinoza claims that there is one metaphysical substance, but there are epistemologically differentiated categories through which the essence of substance can be understood (Shein, 2009, p.531).

-

“Each attribute is conceived through itself, without any other” (Spinoza, 1883 — Part II, Prop. VI Proof)

Clearly, Spinoza’s attributes are distinct from each other. However, the mind-body problem can be overcome, or avoided, because Spinoza’s attributes do not need to interact with each other.

Suppose an alarm clock rings, and a sleepy person is irritated by the noise.

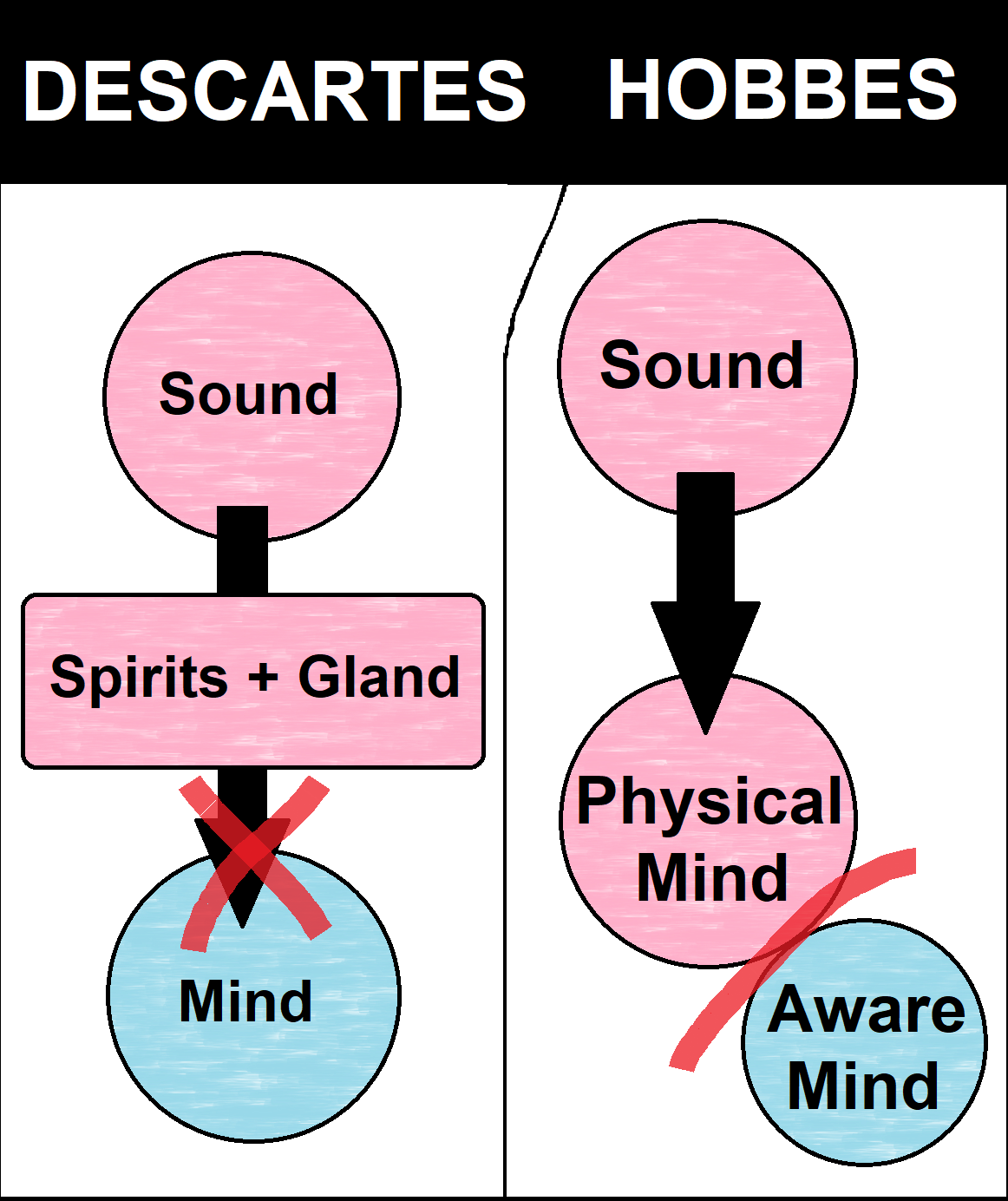

Cartesian metaphysics would argue that the clock produces a sound — physical vibration — which is sensed by the extended body’s ears. This rouses the animal spirits, which agitate the pineal gland. This, mechanistically incoherently, then causes the incorporeal mind to experience the sensation of sound.

Hobbes would propose that the sound from the ringing alarm is sensed by the ears and, through the laws of nature, mechanically prompts the mind’s ratiocination. The process is, of course, not sufficient to give rise to mental awareness and the first-person qualia of sound.

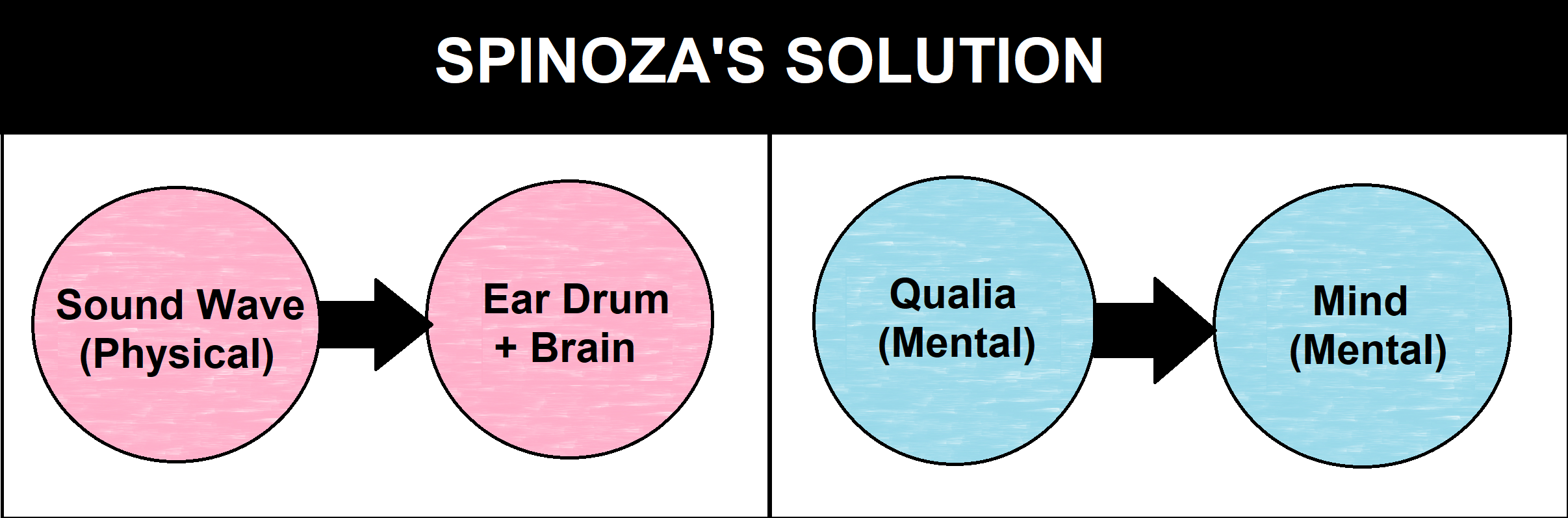

Spinoza’s metaphysics offers two explanations. The first deals with the extended interpretation of the event. The pressure disturbance in the air made by the alarm clock is registered by the extended body, and an impact in the eardrums causes a further physical event — activity in the brain. Nonetheless, this does not actually need to give rise to qualia; it cannot, since each attribute can only be conceived in isolation. There is an epistemologically separate explanation for the sound qua thought. There would be a mental experience of the sensation or qualia of the sound, and this would be metaphysically equivalent to the brain activity observed through the attribute of extension.

-

Thus, Descartes encounters a deep difficulty in explaining how physical events might have mental potency, and vice versa, and Hobbes fails to demonstrate that physical processes entail consciousness. Spinoza, on the other hand, can account in parallel for phenomena of mind and body, or thought and extension, through his attributes. The mind-body problem “is necessarily out of the question” (Matson, 1971, p.572).

-

Moreover, Spinoza’s theory of mind can be reconciled with recent developments in neuroscience.

Antonio Damasio has suggested that the mind is deeply grounded in its physical environment, in which some aspects of cognition — notably emotion — are especially embedded (Rotella et al., 2003, 74). This seems to oppose the delineation of the mind as essentially rational and computational in Descartes' and Hobbes' views respectively.

The mind for Spinoza, though, is the idea of the body; the two are identical in terms of metaphysical substance (Della Rocca, 1993, p.203–204). Consequently, there is still room for a modern understanding of emotions in the Spinozistic mind. His philosophy “anticipates the vision of a subjectivity that does not pre-exist its affects but is, on the contrary, constituted by them” (Johnston & Malabou, 2013, p.7).

It seems that Spinoza’s resolution of the mind-body problem holds firm.

You might be interested in...