AustLit

-

Although Descartes manages to explain the mind in relation to the body on a metaphysical level, separate from notions of thought and extension, it follows from his solution that a mechanistic explanation of mind-body interaction is neither appropriate nor possible.

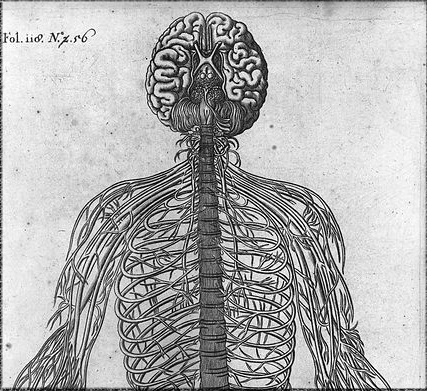

Nonetheless, he does attempt to give a credible account of how a dualistic human functions, yet interactions between thinking and extended substances remain inexplicable under this model. Descartes argues that the two substances can communicate through a “very fine air or wind” (Descartes, 1989, p.22) of ‘animal spirits’ produced in the blood. The movements of these spirits “[cause], [maintain], and [strengthen]” (Descartes, 1989, p.34) the mind’s experience of passions, and moreover are responsible for causing the body to move “in all the different ways in which it can be moved” (Descartes, 1989, p.24).

The spirits, Descartes proposes, can be linked to the mind through the brain’s pineal gland (Descartes, 1989, p.36). This allows the mind to animate the body by changing the course of the animal spirits (Remnant, 1978, p.386), and allows physical phenomena to be communicated to this mind.

-

Descartes proposes that the human body is filled with animal spirits. These allow the mind to deliver commands to the body, and lets the body communicate sensations like pain to the mind. This is essentially equivalent to a nervous system, as shown in this contemporary Cartesian illustration.(in Wikimedia Commons, 2014)249232

Descartes’ mechanistic model of mind-body interaction can be illustrated through visual perception. When the eye sees some stimuli, the optic nerve is agitated and, in turn, so are animal spirits inside the brain. These animal spirits then agitate the pineal gland by forming an image on its surface (Macintosh, 1983, p.334).

The mind therefore receives a representation of the visual stimuli, and can redirect animal spirits to move through the body and cause its muscles to extend or contract — perhaps to point a finger at the perceived object. Thus, Descartes tries to reconcile the causal impotency between extended and non-extended things with a system that mediates mind-body interaction.

-

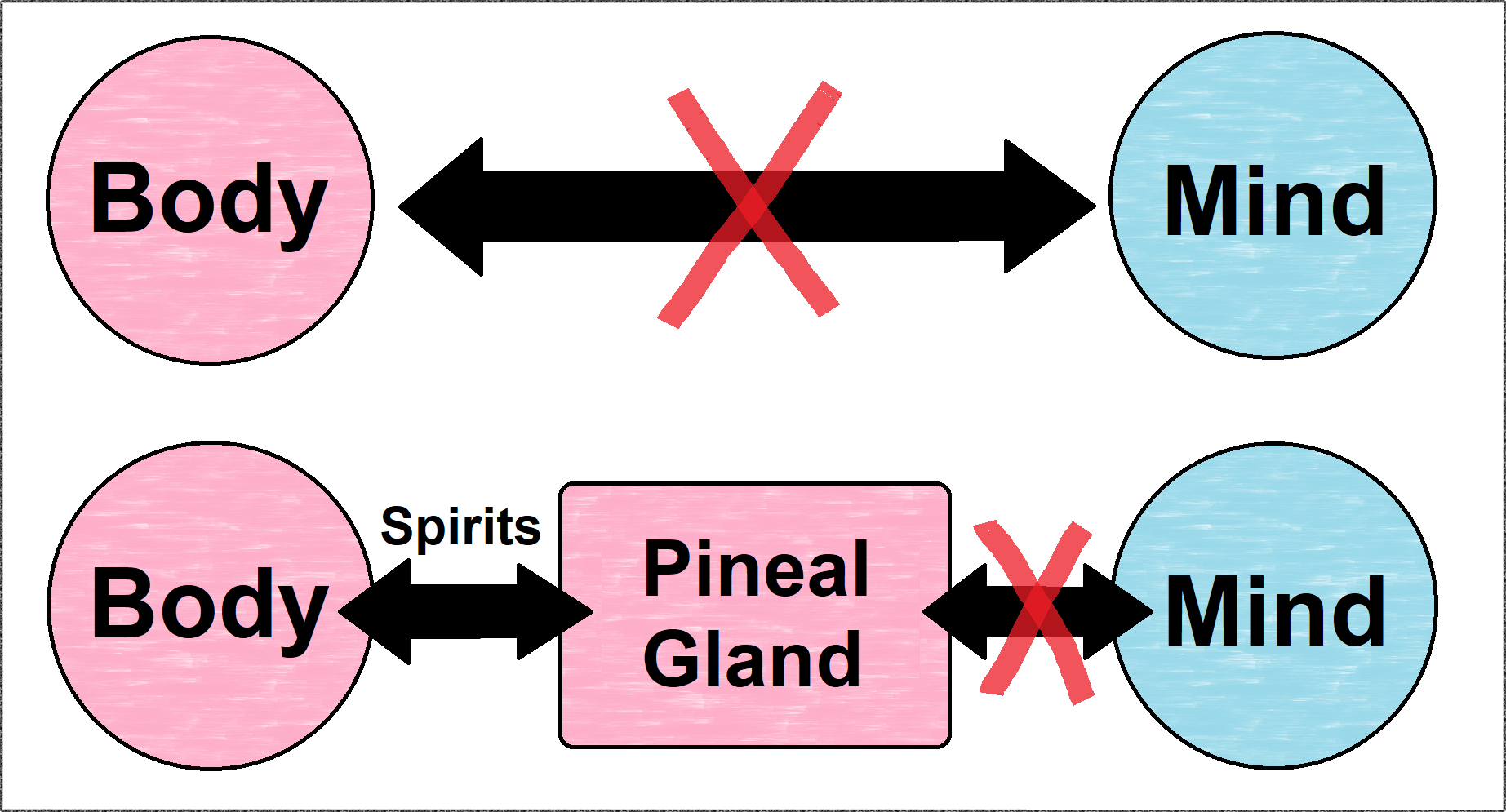

Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, however, in her correspondence with Descartes, points out that this solution is wholly unsatisfactory. In particular, she argues that it seems incoherent that “the soul of a human being … can determine the bodily spirits” (Elisabeth in Shapiro, 2007, p.62). This is because the animal spirits are still extended, non-thinking things like the rest of the human body. Elisabeth writes that it would be impossible for the mind to hold any causal power over the animal spirits, since “being immaterial, it cannot come into contact with them, and being non-extended, it has no weight or figure” (Radner, 1971, p.162). Thus, Descartes’ explanation for how the mind can physically animate the body appears flawed. In another letter, Elisabeth similarly questions how the animal spirits and pineal gland could make any impression on the intellect (Radner, 1971, p.162), undermining Descartes’ case for passions and reducing the mind — contrary to the French philosopher — merely to a sailor on a ship.

Thus, in Elisabeth’s view, the mind-body problem returns in its original form, where the two substances are causally incompatible. By introducing animal spirits, the Cartesian explanation only serves to relocate the mind-body problem to the pineal gland, where the same interactional impotency is encountered.

-

In defence, Descartes’ returns to the mind-body union. He claims that because the union is an irreducible primitive notion, alongside thought and extension, it can only be understood “through itself” (Descartes in Shapiro, 2007, p.65). Just like shape and motion are understood through space or extension, mind-body interactionalism can only be understood through the notion of union. Hence, in assessing the mind-body problem in terms of extension and non-extension, thought and non-thought, Elisabeth would be fundamentally mistaken (Descartes in Shapiro, 2007, p.65).

Descartes therefore argues that the union cannot be comprehended through philosophical processes; it can only be known through the embodied conscious experience (Descartes in Shapiro, 2007, p.70). For Descartes, any other explanation of causation between the mind and body is futile. Cartesian dualism thus fails to produce a mechanistically meaningful solution to the mind-body problem, relying instead on an “unsatisfactory” (Alanen, 1996, p.15) idea that interactions across the substances are simply “instituted by nature” (Descartes in Shapiro, 2003, p.218).

You might be interested in...