AustLit

-

While Cartesian dualism struggles to address the mind-body problem, Hobbes avoids corporeal-incorporeal interactions entirely. He rejects the idea of an incorporeal substance as fundamentally “contradictory” (Hobbes, 1909, p.30) on the grounds that substances must exist in the universe. Hobbes’ claims are thus rooted in a form of monism where physical matter comprises the only metaphysical substance:

“… this is [the substance] which, for the extension of it, we commonly call body …” (Hobbes, 1845, p.102)

-

Consequently, Hobbes sees the human being — and all organisms — in purely physical terms. In this view, people can be described as complex automata, “wholly explicable by the principles of motion and heat” (Moore, 1899, p.65).

Hobbes therefore reduces the mind to a product of physical processes, though his biology does not centre these activities in the brain (Moore, 1899, p.62).

In his philosophy, there is no subsequent mind-body problem; if the mind’s processes are extended, it follows that it can interact with the rest of the extended body.

-

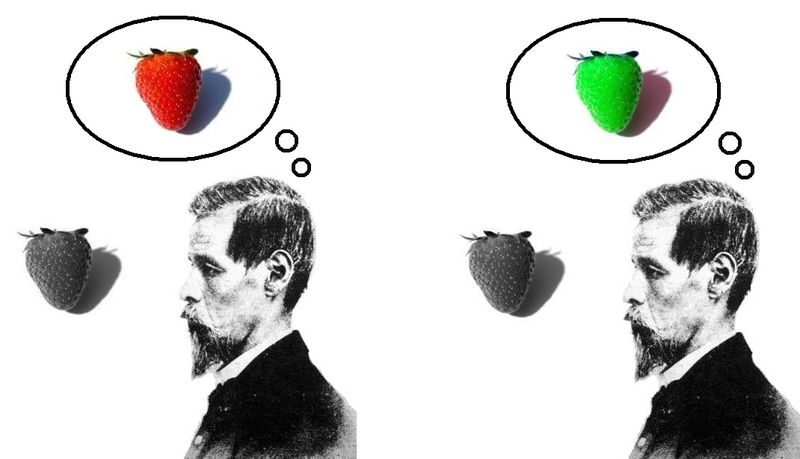

The experience of colour is an example of qualia, an instance of subjective, first-person experience. Jackson argues that no amount of knowledge regarding colour, including the brain's processing of colour, can encompass the experential sensation of colour, which is ineffable.(Wikimedia Commons, 2006)

Physicalist approaches such as Hobbes' materialism, however, tend to be criticised for other reasons, namely that humans’ conscious, first-person experiences are left mostly unexplained. Frank Jackson put forward one of the most famous critiques of materialism in 1982.

“Mary is a brilliant scientist who is, for whatever reason, forced to investigate the world from a black and white room via a black and white television monitor.” (Jackson, 1982, p.130)

In the thought experiment, Mary knows — from the television — every single thing about colour and its physics. Moreover, she is fully aware of how humans perceive and cognitively respond to colour. One day, she sees colour for the first time. Jackson argues that Mary has, by subjectively experiencing and feeling colour, learned something new; no amount of theoretical knowledge could have substituted this first-person qualia. It follows from this that the workings of the mind cannot be fully explained through physical processes (Jackson, 1982, p.130).

Jackson is begging the question, however, by assuming that a subjective experience can never be described by Mary’s existing, theoretical knowledge.

If Mary really knew everything about colour, then she would have a total understanding of how human neurology experiences colour, even if this qualia could never realistically be communicated through finite language. Dennett therefore argues that upon seeing colour in the first-person for the first time, Mary would actually learn nothing new (Dennett, 2006, p.21). She would have already been familiar with the experience that colour would provoke, because her total understanding of colour and the brain would imply an advance knowledge of the sensations caused by any cognitive activity. The 'feeling' of red or any other colour could be preempted or imagined by Mary's theoretical knowledge even in a greyscale world, and hence experiential knowledge could be reduced into theoretical knowledge.

The Hobbesian mind still faces trouble, though. For Hobbes, thought is a process of “ratiocination” (Hobbes, 1845, p.4); concepts are made intelligible by adding and subtracting simpler ideas. Similarly to how a square can be understood as a shape with four sides, equal sides and right angles, a human can be understood as body, as animated, and as rational (Hobbes, 1845, p.4). In this sense, Hobbes’ view of the mind is one which strictly involves “computing” (Cummins, 1988, p.8).

Like a sequence of words, then, the Hobbesian intellect’s reliance on concrete, individuated notions implies an inability to fully construct first-person qualia. The experience of colour, to a Mary unable to access the linguistically-unbounded knowledge described by Dennett, remains ineffable, and Hobbes’ materialism is unable to completely capture the experience of consciousness.

-

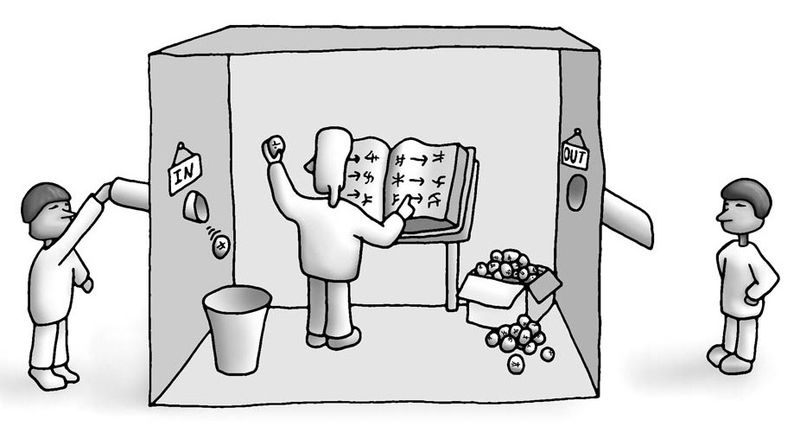

This shortcoming can be further demonstrated by considering the ‘Chinese room’ argument. John Searle (1980, p.417–418) proposes that a person could be placed inside a box and given sentences written in incomprehensible Chinese characters. There, they would consult a book of rules to match the unknown characters to an appropriate set of responding characters, which to them would only seem like arbitrary “squiggles” (Searle, 1980, p.418), then draw these on a piece of paper to be passed outside the box.

Thus, the person inside the box appears to be able to understand and respond to Chinese writing, but really has no idea about the characters’ meanings and no intentionality (Searle, 1980, p.419) in composing their reply. Accordingly, Hobbes’ computational mind, as a series of mechanical processes governed by natural rules of cause-and-effect, is not sufficient to account for first-person awareness.

The English philosopher does succeed in escaping the mind-body problem, but his alternative conception of the mind seems incomplete and therefore exchanges one problem for another.

You might be interested in...