AustLit

-

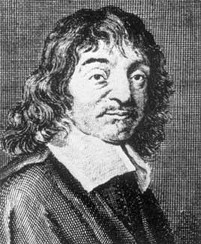

Amid the seventeenth-century escalation of the Scientific Revolution, Aristotelianism was coming under heavy criticism. Classical metaphysics started to be viewed as “incompatible with genuine science” (Lamont, 2009, p.213) and its demands for mechanistic explanations grounded in natural laws. Dismissing hylomorphism as “unknown” (Descartes in Pasnau, 2004, p.31) to his philosophy, Descartes begins his metaphysics by arguing in the Meditations that the mind self-evidently exists as a thinking thing. He cannot doubt this, because the act of doubting only affirms his proposition (Descartes, 2008, p.71).

Descartes later posits that he clearly and distinctly knows that the mind is essentially thinking and non-extended, and that body or matter is essentially extended and non-thinking. He contends that the mind and the body are really distinct as a result (Descartes, 2008, p.116). The philosopher then offers another argument to support this claim on the grounds that the mind is indivisible, but physical things are divisible (Descartes, 2008, p.122).

In other words, since Descartes is sure that the mind exists and excludes every property of body, and vice versa, he argues that they must be separate and independently existing. Cartesian dualism hence concludes that mind and body are reality’s two substances. A human is accordingly composed of an extended body and an incorporeal mind.

-

The mind-body problem arises in attempting to explain — mechanistically — how the human mind might interact with the body. Radner summarises the issue facing Descartes’ dualism:

“How can it be maintained that there is causal interaction between the mind and the body, given the fundamental Cartesian doctrines that mental substance and material substance differ in nature, and that the cause must be adequate to the effect?” (Radner, 1971, p.161)

If the mind is non-extended and does not exist corporeally, it seems incoherent to suggest that it can physically prompt bodily action; there cannot be any materially causal power in non-extended thoughts. Likewise, the body only operates corporeally; it cannot seem to affect or ‘touch’ the mind as an immaterial consciousness.

Despite these apparent incompatibilities, Descartes maintains that the mind and body are not isolated from each other. The mind is “not present in [its] body only as a pilot is present in a ship” (Descartes, 2008, p.118), only observing its affairs intellectually and from a distance, but is fused with the body far more intimately. From the body, the mind experiences “confused feelings of hunger and thirst … and so forth” (Descartes, 2008, p.118).

To account for the human being “as a conscious and embodied agent” (Alanen, 1996, p.3), Descartes proposes a union between mind and body as “a primitive notion on a par with the primitive notions of thinking and extended substance” (Garber, 1992, p.92). This equally irreducible concept of a mind-body union explains the causal interactions between the two otherwise-incompatible substances (Radner, 1971, p.162). The union thus represents Descartes’ attempt to metaphysically escape the mind-body problem.

You might be interested in...