AustLit

-

The idea of a specific relationship between the mind and the body, however, was not an early modern creation. Prior to Descartes, ancient Greek philosophy had developed its own concept of an incorporeal soul. The metaphysical basis of the soul for Aristotle is in his theory of hylomorphism, which contends that all physical objects are constituted by matter and form (Fine, 1983, p.23). He accordingly sees that the matter of any organism is its body, and that the form of any organism is its soul (Aristotle, 2017, p.22). This soul serves to animate and give life to the body-matter, and hence transforms the body into an overall living being (Aristotle, 2017, p.21).

-

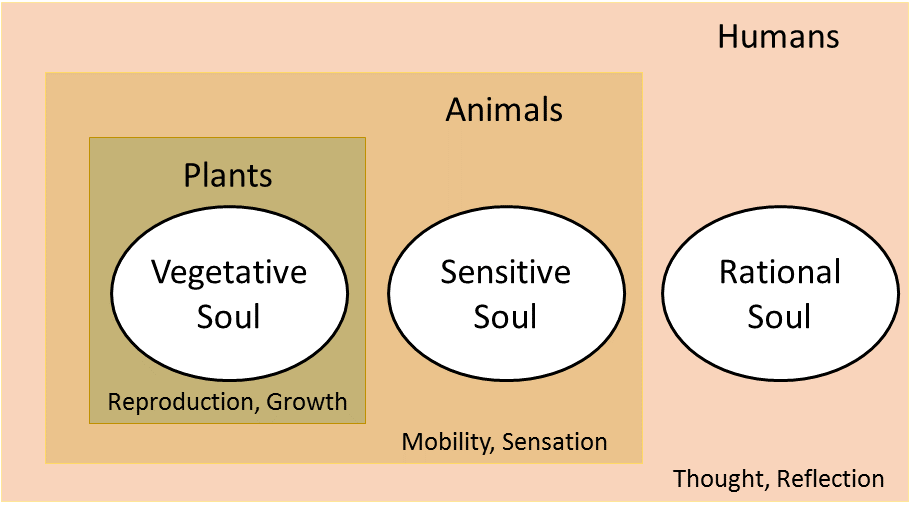

Organisms can then be differentiated into various ‘levels’ through the capabilities of their souls. Plants have a nutritive or vegetative soul, which only allows for subsistence and “the continuation of their own kind” (Bos, 2010, p.822). Animals further possess a sensitive soul, giving them access to a basic level of perception and sensation. Humans, however, have rational souls (Bos, 2010, p.822). Unlike the soul’s other abilities, the intellectual, thinking part of this soul is not “mixed with the body” (Aristotle, 2017, p.53). In this sense, the intellect can be entirely separate from any body-matter, whereas faculties like visual perception are always dependent on physical organs.

Aristotle concludes that the intellect is immaterial (Frede, 1995, p.105). This is especially evident in his assessment of the intellect’s ‘active’ component as imperishable; Yaqub (2012, p.17) argues that because this intellect is not bound to the demise of the body, Aristotle would see it as capable of existing on its own. Caston (2012, p.337), on the other hand, rejects the idea that the soul could exist independently, citing the perishability of Aristotle’s ‘passive’ intellect. Even then, Caston concedes that Aristotle does hint at a dualist stance (Caston, 2012, p.337). The intellect is incorporeal; the body is physical.

Aristotle, however, accepts that the soul could directly interact with a physical body (Carter, 2019, p.96). The philosophy of antiquity does not, therefore, seem to face any deeper ‘problem’ or incompatibility in explaining these mind-body interactions, unlike Descartes.

You might be interested in...