AustLit

-

This trail collects a range of items to enhance readers' engagement with A Fortunate Life.

– Part One provides an overview of A Fortunate Life and its author, and its adaptation for television.

– Part Two examines Facey's text as an example of autobiographical writing, highlighting factual anomalies, the transition of a life story from an oral to a written version, and the narrative impact of Facey's limited literacy (including his use of language).

– Part Three focuses some of the major themes in A Fortunate Life: World War I and childhood.

– Part Four looks at A Fortunate Life through the lens of mythmaking.

– Part Five offers suggestions for wider, contemporaneous reading.

– Part Six provides tips for further research.

Click on the hyperlinks below to visit AustLit records and external references. Some of the critical works and other resources are available online.

-

See full AustLit entry

'Born in 1894, Albert Facey lived the rough frontier life of a sheep farmer, survived the gore of Gallipoli, raised a family through the Depression and spent sixty years with his beloved wife, Evelyn. Despite enduring hardships we can barely imagine today, Facey always saw his life as a "fortunate" one. A true classic of Australian literature, his simply written autobiography is an inspiration. It is the story of a life lived to the full – the extraordinary journey of an ordinary man.' (Penguin Australia abstract)

(...more) -

Image sourced from Browse BiographySee full AustLit entry

Image sourced from Browse BiographySee full AustLit entryAlbert Barnett Facey, the youngest of seven children, spent his early years at Barkers Creek in Victoria. Following the death of his father and the re-marriage of his mother, Facey lived with his grandmother. Soon after the turn of the century, and while still a young boy, he moved to Western Australia, with his grandmother and some of his siblings, and worked as a farmhand for several years before re-locating briefly to Perth. He went on to work at a range of rural jobs around Western Australia and then joined a boxing troupe.

-

For many years Albert, 'Bert', Facey orally recounted episodes from his life to family members. After his retirement he began to record these events in written form. Three draft manuscripts were written in exercise books at the kitchen table, under the encouraging eyes of his wife Evelyn. The project, comprising three handwritten drafts, was completed between 1958 and 1976 (the year of Evelyn’s death).

The draft manuscripts were presented to Fremantle Arts Centre Press (FACP, now Fremantle Press) with the intention of producing a small number of copies for family members. Ray Coffey, senior editor at FACP, quickly recognised the story’s wider appeal and published Facey’s autobiography, A Fortunate Life, for the commercial market in 1981. The book won the Douglas Stewart Prize for Non-Fiction in the New South Wales Premier's Literary Awards and the National Book Council’s Banjo Award for Non-Fiction.

By 2013, A Fortunate Life had sold more than one million copies. It has been adapted for stage and screen, produced in audio versions, and translated in Japanese and Chinese. Extracts from A Fortunate Life have been included in themed anthologies ranging from bush writing and ANZAC writing to stories of Australian men and stories of Australian women.

A Fortunate Life is included in Jane Gleeson-White’s Australian Classics: 50 Great Writers and Their Celebrated Work. In her summary of the book’s classic status, Gleeson-White describes A Fortunate Life as ‘quintessentially Australian’ (124). ‘As well as touching on key moments of Australian history', Gleeson-White says ‘Facey also lived out many of the themes from the realm of Australian myth: the lone boy in the bush, the lost child, the cattle drover, dingo combatant, snake battler, the boxer, the unionist … Facey’s itinerant life, his adventures attuned to his times, his urge to tell his stories over and over until they are recorded at last, evoke the myth of Odysseus, the Greek warrior of Troy (near present-day Gallipoli); in many ways A Fortunate Life is an Australian Odysseus’ (127).

-

This essay, an introduction to A Fortunate Life, was written for the Reading Australia project. It discusses Facey's life and character, and the genesis of his autobiography. The essay highlights a range of reader responses to Facey's story and argues that 21st century readers should return to the book 'to rescue the text from misreadings that have grown up around it and to hear Albert Facey's testimony free from outside intervention'.

Available online at Reading Australia.

-

Television Adaptation of A Fortunate Life

A mini-series adaptation of A Fortunate Life, written by Ken Kelso, aired on Australian television in 1985. The Australian Screen website provides detailed information on the mini-series including video clips, comments from director Marcus Cole and a map with links to A Fortunate Life's Western Australian locations. Click here to visit the Australian Screen site.

Further information on the series is available on the Australian Television Information Archive website.

Here is an excerpt from Part Two of the four-part series. (The original music for the mini-series, composed by Jon English, can be heard here.)

http://www.youtube.com/embed/M23-vVHa8yY -

A. B. Facey's home from 1924 to 1934, Wickepin, Western Australia

This home was re-located from the outskirts of Wickepin to the main street of town in 2000.

See Wickepin: A Fortunate Place for further information on the region.

-

‘Autobiography is a particularly unruly beast which has not yet been broken in.’

-

Don Grant, in ‘Seeking the Self: Imagination and Autobiography in Some Recent Australian Writing’, highlights some of the questions posed by autobiographical writing – ‘questions about truth, reality, accuracy [and] problems of addresser identity’. Grant asserts that autobiography is really ‘an imaginative act that has little to do with presenting reality, less to do with establishing truth, but most of all to do with making meaning’ (309). The image presented by the autobiographer is ‘necessarily an inaccurate image’ (311).

A number of scholars have the addressed issues of accuracy and truth-telling in Facey’s A Fortunate Life. James Hurst, in ‘The Mists of Time and the Fog of War: A Fortunate Life and A.B. Facey's Gallipoli Experience’ (2010), notes anomalies in Facey’s account of some World War I battles and of his participation in them. Facey ‘describes actions rarely mentioned outside the Australian Official History ... These inconsistencies bring into question whether Facey’s biography is fact, fiction, or a combination of both, and if the latter, in what balance.’ (74) An examination of primary sources, however, swings ‘the pendulum of doubt back in Facey’s favour’ (75). Hurst concludes that the anomalies in the text are ‘entirely understandable’, given Facey’s ‘age, education and life experiences at the time’ (88).

-

Some A Fortunate Life commentators focus on the text’s origin in oral form and the impact of that genesis on the written narrative. Wendy Capper, in ‘Facey’s A Fortunate Life and Traditional Oral Narratives’ (1988), notes oral storytelling elements that carry over into Facey’s book – repetition, episodic structure, generalised characterisation, and the tension between the wandering hero and a yearning for home. Facey’s illiteracy during his childhood and into his early adult years binds him to the oral storytelling form when he puts pen to paper (281).

Joan Newman, in ‘Reader-Response to Transcribed Oral Narrative: A Fortunate Life and My Place’ (1988), draws attention to Facey’s ‘recurrent tropes and motifs, typical of oral narrative’ (377). This theme is also picked up in Carolyn Bliss’s ‘The Mythology of Family: Three Texts of Popular Australian Culture’ (1989) and in Anna Johnston’s ‘Australian Autobiography and the Politics of Narrating Post-Colonial Space’ (1996).

-

Ivor Indyk, in ‘A. B. Facey’s Australian Autobiography’ (1987), puts Facey’s use of language under the microscope, honing in on the repeat use of words such as ‘beautiful’, ‘lovely’, ‘nice’ and ‘terrible’. This simple language, common in the vocabulary of a formally uneducated man, enables Facey to construct a ‘moral topography’ through which to understand the world (34). Indyk also comments on Facey’s use of narrative detail. It provides a 'homeliness' that puts Indyk in mind of the writing styles of Henry Lawson and Joseph Furphy (38).

Another structural feature drawing the attention of commentators is the relative weight given by Facey to his early years compared to his life after World War I. Of A Fortunate Life's six sections, five deal with the period 1894-1915, while only one covers the span 1915-1976. Anna Johnston, in ‘Australian Autobiography and the Politics of Narrating Post - Colonial Space’ (1996), sees this division as ‘particularly Australian’ and ‘immediately recognisable to readers’ familiar with the styles of Lawson, Furphy and ‘Banjo’ Paterson.

Further comments on A Fortunate’s Life’s structure can be found in Carolyn Bliss’s ‘Categorical Infringement: Australian Prose in the Eighties (1991) where Bliss couples Facey’s work with that of Sally Morgan in My Place and John Bryson in Evil Angels.

-

Clare Rhoden’s article ‘What’s Missing in This Picture?: The “Middle Parts of Fortune” in Australian Great War Literature’ (2010) places section five of A Fortunate Life (dealing with Facey’s wartime experiences) in the wider context of Australian literature of World War I. This literature, she argues, is often interpreted via the ‘simple binary opposition’ of disillusion and disenchantment versus heroic narration. Rhoden contends that such an either/or approach is unhelpful. She suggests that many accounts of the Great War, Facey’s among them, canvas the ‘irreducibly complicated nature of experiences in and responses to war’ (21, 22). A deeper examination of World War I literature reveals ‘a dense, multi-faceted textual remembrance’ (21, 22).

For further World War I background and context, see AustLit's World War I in Australian Literary Culture research project. The project includes coverage of the way the 1914-1918 war has appeared in literature, film, and other forms of storytelling from the conflict's beginning to the present.

-

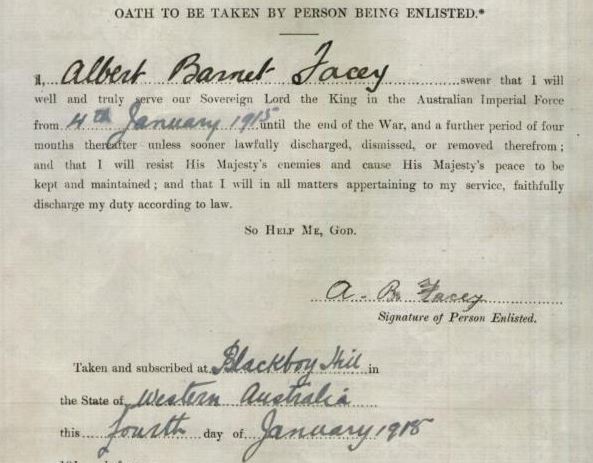

Oath of Allegiance

A. B. Facey enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force on 4 January 1915. A digital copy of his service record, including the Oath of Allegiance, is available via the National Archives of Australia.

Note the spelling of Facey's second name throughout this document as Barnet, rather than the more common Barnett.

-

Facey’s autobiography reveals a shift in the understanding of childhood from the early to the late twentieth century. In her afterword to the 2005 Penguin revised edition of A Fortunate Life, Jan Carter comments on the number of readers who responded to Facey’s depiction of his early life. They commiserated with his ‘unloved childhood’ and noted that the book had given them a new appreciation of the way in which the role of the child in the family had changed markedly since Facey’s era. Carter writes: ‘Facey hardly had a childhood, as we think of childhood today ... [his] portrait of childhood is a social history of changes in the status of children this century’ (418).

-

‘Autobiographical texts are important to national self-fashioning providing the historical "clothes" for the modern nation to inhabit.’ (Anna Johnston, 'Australian Autobiography and the Politics of Narrating Post – Colonial Space, Crossing Lines: Formations of Australian Culture (1996): 132)

-

Albert Facey’s life can be examined through the lens of Australian mythmaking – he is ‘lost in the bush’ as a child, he is the archetypal battler, the itinerant swaggie and rouseabout, and the ANZAC soldier.

Some critical articles deal with these aspects of Facey’s position in Australian literature. Heather Wearne, in ‘The “Fortunate” and the “Imagined”: Landscape, Myth and Created Self in A. B. Facey and David Malouf’, explores ‘the myths of experience in the Australian landscape’, contrasting Facey’s experience with Ovid’s exile in David Malouf’s An Imaginary Life. Where Facey is seemingly isolated and forgotten (151), Malouf proposes a world where exile offers the hope of restoration, renewal and affinity with the landscape (160).

Another aspect of Facey’s world is explored in Carolyn Bliss’s ‘The Mythology of Family: Three Texts of Popular Culture’ (1989) in which she contends that Facey’s book, in common with Sally Morgan’s My Place and John Bryson’s Evil Angels, privileges the nuclear family (62). Bliss concludes that Facey’s ‘investment in the myth of family’ pays off in the ‘enabling security’ (71) of his wife and offspring. Even the writing of his book, with his family’s encouragement, ‘functions as a powerful compendium of myth (65).

As noted in the section on ‘Childhood’ above, A Fortunate Life highlights some changes in the Australia psyche. One of these shifts is highlighted in Sarah Bell’s ‘The Wheatbelt in Contemporary Rural Mythology’ (2005). Bell interviews 21st century West Australians and asks the question ‘What do you think is the place of the wheatbelt in Western Australian mythology?’ The answers indicate the displacement of ‘romantic rural mythologies of the “Aussie battler”’ and a move towards a sense that the wheatbelt is ‘a place of crisis, misfortune and destruction’ (188).

-

As already noted, Albert Facey’s A Fortunate Life can be read alongside other Australian works of autobiography and fiction. Here are some further ideas for wider, comparative reading:

- The Treatment of Returned Servicemen

My Brother Jack: A Novel by George Johnston

The Watcher on the Cast-Iron Balcony: An Australian Autobiography by Hal Porter

- The Experience of Pioneering Settler Women in Western Australia

Nothing to Spare: Recollections of Australian Pioneering Women by Jan Carter

- Contemporaneous Bush Tales

Children of the Bush and While the Billy Boils by Henry Lawson. (See also J. B. Hirst’s The World of Albert Facey for connections between Facey’s and Lawson’s writing styles and settings.)

Such Is Life: Being Certain Extracts from the Diary of Tom Collins by Joseph Furphy

A. B. 'Banjo' Paterson: Bush Ballads, Poems, Stories and Journalism by A. B. ‘Banjo’ Paterson

-

Parallel Reading Suggestions - Autobiographies and Bush Tales

-

- There is additional information in AustLit about A. B. Facey and A Fortunate Life – follow the links within Facey’s author record and the record for A Fortunate Life to explore more.

- To further investigate subjects such as autobiographical writing, go to the AustLit search page and explore the Advanced Search options. For help on building searches, visit the 'How to Search AustLit' page.

- See the Australian Dictionary of Biography entry for Albert Facey for more details of his life.

-

Digitised Newspaper Resources via Trove Australia

To discover more about social conditions in Western Australia during Facey’s lifetime, visit the National Library of Australia’s Trove website, particularly its digitised resources. Several newspapers corresponding to Facey’s residence in Western Australia have been digitised including the West Australian and the Wickepin Argus. Details of events in Facey’s life, such as his marriage to Evelyn Mary Gibson (see below), can also be traced through Trove's digitised resources.

-

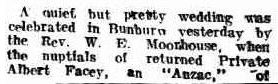

The 'Wickepin Argus' Report on the Marriage of Albert Facey and Evelyn Gibson

On 22 August 1916, the Wickepin Argus reported that 'the nuptials of returned Private Albert Facey, an "Anzac", of Subiaco, and Miss Evelyn Mary Gibson, eldest daughter of Mr Geo Gibson, foreman of the Bunbury Council, and Mrs Gibson, of Constitution Road, were celebrated'.

You might be interested in...