AustLit

-

These learning resources and an associated teacher workshop were originally developed by Lindsay Williams for the Teaching with BlackWords Symposium held at The University of Queensland on 22 November 2017, and supported by the School of Communication and Arts. These resources were updated in October 2019 in time for a new round of workshops in Rockhampton and Mt Isa.

Below is a slideshow of Lindsay's presentation and a set of suggested activities for the classroom and teacher professional development. You can also download a PDF of these lesson plans. These should be seen as a possible starting point.

This material is made available under licence by AustLit. Please acknowledge both AustLit and Lindsay when using the lesson plans and resources.

Suggested citation: Williams, Lindsay. 'Challenging Terra Nullius of the Mind.' Rev. ed. St Lucia, Qld: AustLit, 2019.

-

The following is a brief history of the evolution of this resource by Lindsay Williams, the author:

"I am a white settler educator and originally took this project on with some trepidation, aware that it was problematic for me to develop resources about literature written by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander authors. However, I have always considered myself progressive, strongly anti-racist and pretty well informed about Australia's frontier wars, so agreed to work as part of a team (including Professor Anita Heiss) on the project.

The original workshop and set of resources was inspired by Julianne Schultz's introduction to the Griffith Review 58 (2017). The entire introduction is worth reading, but she states that the aim of the edition (with the theme Storied Lives) was to 'build a more nuanced and insightful perspective on what it means to be an Australian today" (p. 11). The old stories, she argues, 'have also become increasingly threadbare, and increasingly fail to capture the contemporary reality or complexity of the past' (p. 8). One aspect of countering this, she argues later, is ensuring space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories, necessary if 'we are to eliminate terra nullius of the mind' (p. 11; my emphasis).

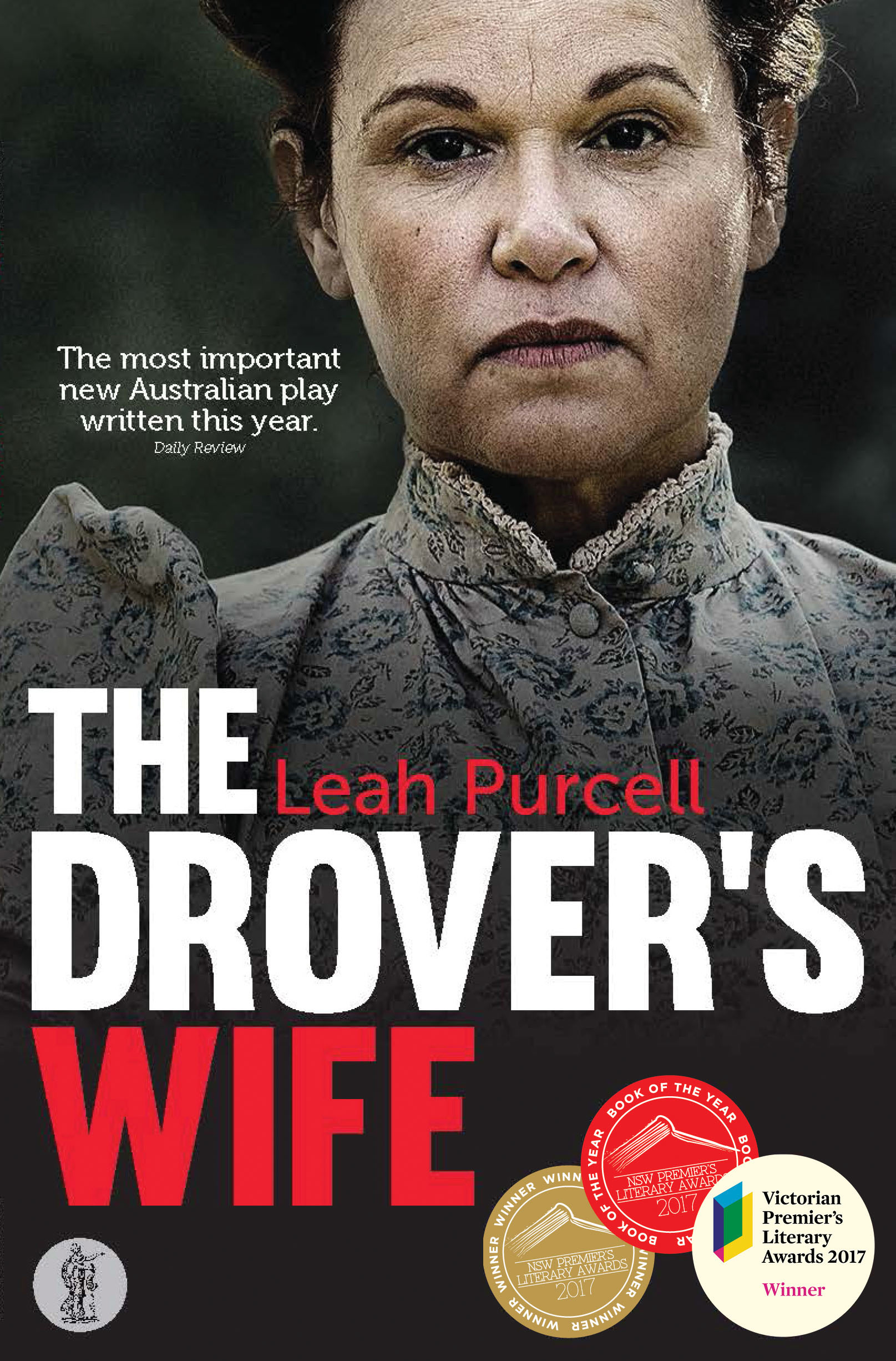

With these ideas in mind, my one-hour workshop was designed to raise English teachers' awareness of the silences in settler colonial texts, juxtaposing the original version of 'The Drover's Wife' by Henry Lawson with Leah Purcell's 2016 reimagining of the story as a play which 'activates all the characters' (p. vii). I was quite satisfied with the workshop as a way of starting a discussion about the deeply colonial nature of the original story and its erasure of Aboriginal perspectives on 'the bush' (to use Lawson's term).

However, in the two years since the workshop was developed I have consciously immersed myself in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island literature (plays, novels and poetry), as well as anti-racism and Critical Race Theory writings. For me, this has been nothing short of a revelation, making visible the gaps in my understandings and raising my awareness of how deeply implicated I am in colonialism, despite my best, progressive intentions. One result of this learning is a revision of the original workshop.

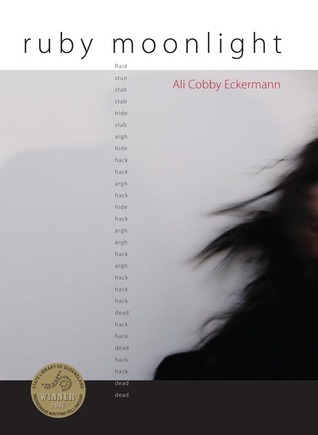

The main development is to de-centre the colonial text (Henry Lawson's short story) and centre Aboriginal voices and perspectives. This means placing Purcell's story at the centre, and opening space for further Aboriginal voices, especially Yankunytjatjara and Kokatha poet, Ali Cobby Eckermann, and artist and Waanyi man, Gordon Hookey. These texts are foregrounded and are used as the lens through which Lawson's story is then read resistantly, forcing a reinterpretation of events. For example, rather than an Australian-gothic tale of a family left alone, isolated in a desolate, forbidding landscape far from civilisation, it becomes clear that Lawson's colonial story actually reveals the white settlers' deep misunderstanding of human's relationship with nature and Country.

I make no claim that the revised version is perfect. For instance, I'm still not sure if bringing together voices of people from different Countries is appropriate. However, I think the new version might help non-Indigenous English teachers look afresh at their units and consider how centring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices, understandings and knowledge might help transform our subject and contribute in a practical manner towards truth telling and reconciliation."

Lindsay has also created a starter list of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander texts (non-fiction, novels, podcasts, news sites and Twitter accounts) for non-Indigenous, secondary English teachers. An earlier version was originally published in Words'Worth, the journal of the English Teachers Association of Queensland.

-

-

During the course of these activities, students will:

- engage with texts written by a range of Aboriginal authors

- consider how worldviews (attitudes, values, beliefs etc) shape the way identities and landscape/Country are represented

- evaluate representations of Aboriginal peoples and the Australian landscape in a play, short story, poem and interview, with a focus on reading resistantly the encoding of Terra Nullius and the construction of Aboriginal voices in settler colonial texts

- consider ways to centre Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander texts, partly for their own literary and cultural value and partly in order to disrupt and reinterpret settler colonial texts.

Teachers might also use these activities to:- discuss issues with using ‘classic’ Australian texts in the English classroom

- consider the role of BlackWords in assisting English teachers to contribute to reconciliation, truth-telling and a more just Australian society.

-

Leah Purcell’s play The Drover’s Wife is rich in potential as a text to study in Senior English alongside more traditional stories of the Australian frontier. In particular, Purcell’s work appropriates Lawson’s iconic story, infusing it ‘with First Nations and Women’s history, calling into question the shameful treatment endured by both, at the hands of white men’ (Leticia Cáceres in Purcell 2016: xii).

With regard to the new English syllabus, a comparison of these narratives would suit very well ‘Unit 3: Textual Connections’ (see ACARA 2017: 3) and contribute (amongst others) to the following general syllabus objectives (ibid: 4):

4. make use of and analyse the ways cultural assumptions, values and beliefs underpin texts and invite audiences to take up positions.

5. use aesthetic features and stylistic devices to achieve purposes and analyse their effects in texts.

With regard to the latter, this workshop will (briefly) focus on the use of imagery, representation, dialogue, motif, juxtaposition, approaches to characterisation, and literary patterns and variations.

For teachers, the aim of these activities and resources is not to provide exhaustive advice on how The Drover's Wife might be used in a unit; instead, the aim is to open conversations about how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander texts can be centred and used to help non-Indigenous people to read colonial texts (such as Lawson’s short story) afresh, allowing their underlying Discourses/worldviews to be critiqued. This is not to suggest that the original cannot be read and enjoyed still: Leah Purcell herself states that ‘ […] I’ve grown up with this story and love it’ (Purcell 2016: vii). However, as has been suggested, in contemporary Australia, tales such as Lawson’s ‘ […] sound thin and one dimensional, like music on a dusty vinyl record that’s been played a few too many times. New versions might seek to add nuance and complexity […] the first Australians are no longer prepared to be rendered invisible and silent ’ (Schultz 2017: 9). This curriculum activity sequence is a modest attempt to help English teachers open up their practice and encourage them to make use of resources like BlackWords to help them do so.

Although the activities below are based on short extracts from a range of texts, teachers could expand the scope and study at least one of the texts (e.g. Purcell's The Drover's Wife or Eckermann's Ruby Moonlight) in full.

A caution: Purcell's play does contain a rape scene, brief in terms of words on the page, but integral to the story. Also, there is in the second half of the play some high level coarse language (although nothing that would not now be heard on free-to-air television after 8.30pm). Please take this into consideration within the context of your own school community when making text selections. Regardless, as this plan shows, extracts from the play can be used if desired and all the activities would transfer to the study of alternative texts.

-

The first extract is from Leah Purcell's 2017 play, The Drover's Wife. It tells the story of a pregnant wife left to fend for herself while her husband, Joe, is away droving. She is helped by an Aboriginal man, Yadaka - and in this excerpt he tells his story.

-

SETTING

A two room shanty, in the dense scrubland of the Alpine country of the Snowy Mountains.

[This scene from pages 9 to 11 occurs the afternoon after the DROVER’S WIFE, 40, has lost a child while giving birth. Reluctantly, she had required the assistance of YADAKA, a 38-45 year old black man.]

YADAKA goes to the water barrel to clean himself up with a rag.

DROVER’S WIFE: It was an old gin that told me that. ‘Don’t be afraid to cry hard for ya dead.’

Beat.

Those blacks haven’t come back through here in years.

YADAKA: Fences are up, harder to cross country, and white can shoot on sight.

DROVER’S WIFE: It is ya lucky day then.

Different story if my Joe was here.

YADAKA: Sure of it.

Awkward silence.

Same skin.

DROVER’S WIFE: Pardon?

YADAKA: That old woman you talk of, same mob. Same skin.

DROVER’S WIFE: I’d say she was darker than ya.

YADAKA: I mean, family way. I know whose country this is. Who can do business on it. My adopted clan, Ngambri Walgalu.

DROVER’S WIFE: Meanin’?

YADAKA: I’m not from here. I was adopted in. North. I’m heading home. Tryin’ to. I was left in Melbourne.

DROVER’S WIFE: Melbourne?

YADAKA: I ran away with a circus.

She chuckles to herself.

DROVER’S WIFE: Now you havin’ a lend of me.

YADAKA: No, I did.

South African circus, ‘Fillis Circus’. I was good with the horses and bears.

They did their show, startin’ in my homeland of the Guugu Yimithirr, rainforest and coloured sand country, missus. All the way down the coast.

I calmed a bear in rough seas. I was good with the children that came to watch.

DROVER’S WIFE: Closest thing to a circus we get is Market Day in town. Big fanfare durin’ the day and the drunken clowns come out at night!

They share the moment.

YADAKA: I was with the circus for, two years. They left me then, des…des-tit –

DROVER’S WIFE: Destitute.

YADAKA: That was my first arrest. Destitute.

In prison, dead for; cold, no clothes and a man of God, Father Matthews, helped me.

Got me out, clothed me, gave me a white name, I don’t use it.

He took me to a mission, west…taught me to read, write and play the tuba.

DROVER’S WIFE impressed on hearing about the tuba.

But bein’ there listen’ to Father Matthew’s stories about his God wasn’t getting’ me closer to my homeland though.

I went then. Slipped away into the shadows, missus.

Went on my own walkabout. Followin’ the range; The Great Dividin’. It goes right up into my homelands in Queensland.

DROVER’S WIFE: Long way. My Joe done some drovin’ up there.

YADAKA: Takin’ the mountain range, I ran into other mobs, see. I came to the Snowy Mountains with them for the big Bogong moth, Uriarra…to eat and…dance and…

DROVER’S WIFE: Like a celebration.

YADAKA: Yes. Then one night I saw this beautiful woman…her skin oiled with the Bogong moth fat, shining like a full moon…and when she danced…smooth like a shallow runnin’ water over river rocks…

DROVER’S WIFE becomes a little uncomfortable with his talk. He sees this but continues on:

I had to be adopted to be the right skin for her. To join with her. So, I was adopted into the Ngambri Walgalu. Settled in with them.

-

The next extract ('Birds') is from Eckermann's verse novel about the aftermath of a massacre in South Australia. 'Birds' appears shortly after the massacre and explores the empowering knowledge that nature will take care of the traumatised survivor, a young woman.

-

Birds

senses shattered by loss

she staggers to follow bird song

trust nature

chirping red-browed finches lead to water

ringneck parrots place berries in her path

trust nature

honeyeaters flit the route to sweet grevillea

owls nest in her eyes

trust nature

crimson wattlebirds turn shades of green

blue wrens turn camouflage-brown

trust nature

pied butcher birds lay trinkets in her path

grey fantails flutter a soft revival

trust nature

apostle birds flicker on the edge of her eyes

emus on the horizon stand like arrows

trust nature

the woman turns

follows the emus

-

The following extract is from an interview with painter Gordon Hookey about his large-scale painting 'Murriland!'. The interview explores the meanings of his painting and discusses the British Invasion and the impact of the legal fiction of terra nullius on the way settler colonials perceive the land. It starts by discussing a neologism he created, terraism.

-

Gordon Hookey

[...] Anyway, the word 'terraism' I took from the doctrine that the British used to colonise us: terra nullius. Terra is a Latin word meaning 'land', and nullius means 'void' or 'belonging to nobody'. So that meant they saw Australia as uninhabited; basically, they saw us as animals. Therefore, it was okay to colonise us. I took terra and just put '-ism' behind it [to capture this idea and play with the notion that that settlers were a type of terrorist] [...]

A little later in the interview...

Vivian Ziherl (Interviewer)The settler psyche, I would argue, involves a profound cognitive dissonance produced by the paradoxical nature of the frontier. The settler is drawn towards the frontier because of its sense of boundlessness and opportunity, yet at the same moment always turns away from it as a space defined by a perceived threat from the outside. This threat exists in the immediate sense of the land but also in terms of an outside of modernity itself; of that which is native, which is barbaric, which is outside the disciplining of history. The treat is perceived as physical but is also deeply psychic. One might become mad in this place, untethered from 'civilisation'. [...]

Gordon HookeyThe interior is viewed as resource, not as land, not as a living entity. Right from the start, those colonising Australia had always tried to transplant England, from the animals to the fences, the hedges: we are away from home, let's bring home here. To me, they still haven't got over that. They are still trying to replicate Europe, or the US in many cases, never looking at the land itself and coming to terms with it.

Not coming to terms with the land and the environment is also another meaning for terraism, with the land striking back in the form of drought, flood, fires, all these things that Australia fears. When there is a flood or a drought, they go into almost a state of fear.

-

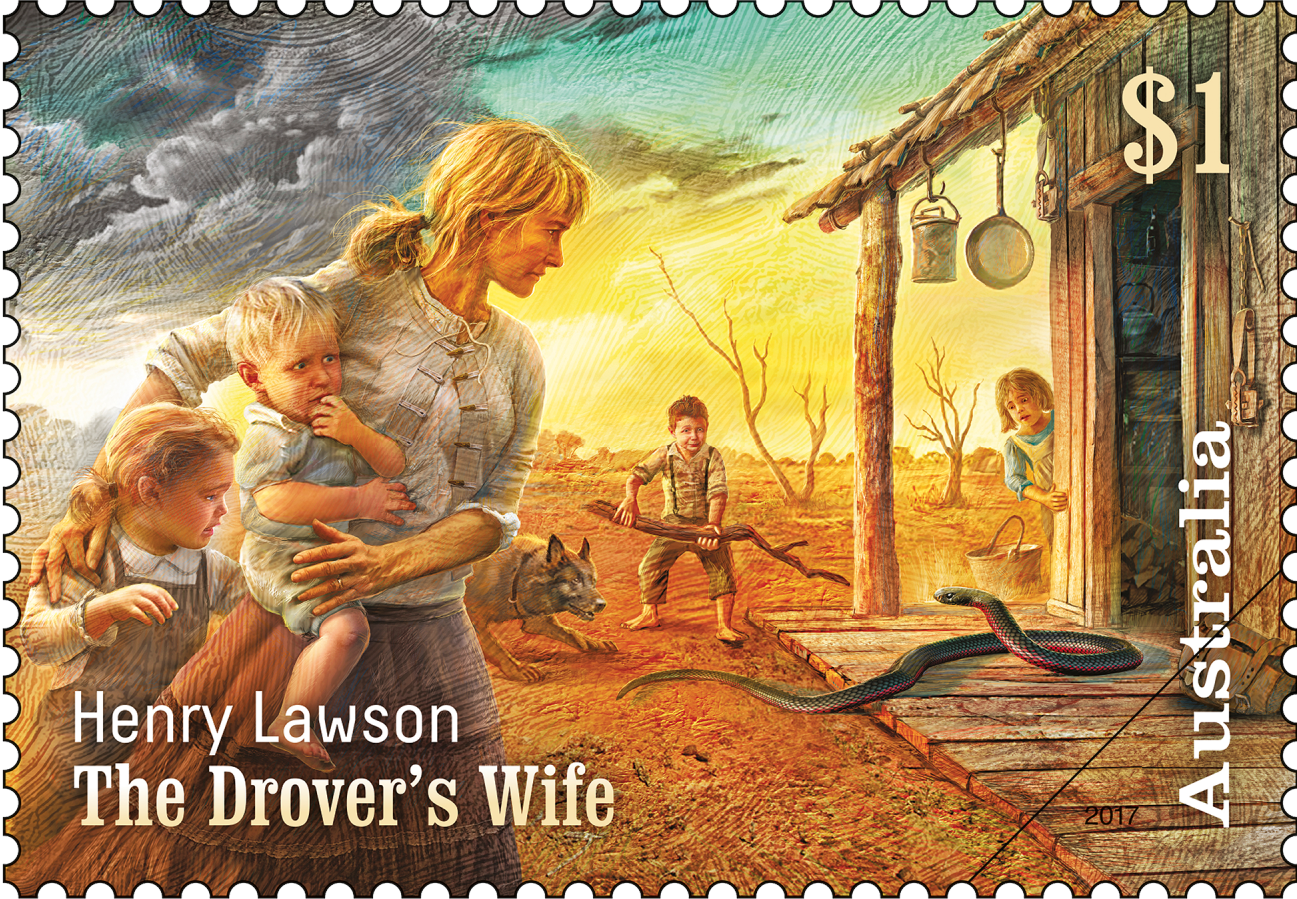

Henry Lawson (1867-1922) is colonial writer. He is probably best-known for his stories about the harshness of the Australian 'bush' - at least for settler colonials. 'The Drover's Wife' is one of his most famous short narratives, telling the story of an unnamed wife of a drover left at home with her children while her husband is away. On this one particular night, a black snake enters their two-roomed house and a terrifying night begins...

A selection of extracts from the 'The Drover's Wife' are printed below. To read a copy of the complete story from the Bulletin magazine (1892), click here, or read a clean copy of the text in AustLit here.

-

The first extract is the opening where the setting ('the bush') is described. The last two extracts are where Lawson introduces Aboriginal characters - the only places they are mentioned in the text.

THE TWO-ROOMED house is built of round timber, slabs, and stringy-bark, and floored with split slabs. A big bark kitchen standing at one end is larger than the house itself, verandah included.

Bush is all around – bush with no horizon, for the country is flat. No ranges in the distance. The bush consists of stunted and rotten native apple trees. No undergrowth. Nothing to relieve the eye save the darker green of a few sheoaks which are sighing above the narrow, almost waterless creek. Nineteen miles to the nearest sign of civilization – a shanty town on the main road.

The drover, an ex-squatter, is away with sheep. His wife and children are left here alone.

-

Later…

The last two children were born in the bush – one while her husband was bringing a drunken doctor, by force to attend her. She was alone on this occasion, and very weak. She had been ill with a fever. She prayed to God to send her assistance. God sent Black Mary – the “whitest” gin in all the land. Or, at least, God sent “King Jimmy” first, and he sent Black Mary. He put his black face around the door-post, took in the situation at a glance, and said cheerfully: “All right, Missis – I bring my old woman, she down alonga creek.”

One of her children died while she was here alone. She rode nineteen miles for assistance, carrying the dead child.

-

And later still…

Yesterday she bargained with a stray blackfellow to bring her some wood, and while he was at work she went in search of a missing cow. She was absent an hour or so, and the native black made good use of his time. On her return she was so astonished to see a good heap of wood by the chimney, that she gave him an extra fig of tobacco, and praised him for not being lazy. He thanked her, and left with head erect and chest well out. He was the last of his tribe and a King; but he had built that wood-heap hollow.

-

The purpose of this activity is to gain an insight into how Leah Purcell, a Goa-Gunggari-Wakka Wakka Murri woman, writer and actor, represents Country and the Australian landscape - in order to appreciate her play and its characters and, later, to make comparisons with settler colonial representations (especially in Henry Lawson's short story, 'The Drover's Wife').

Students will be reading Text 1, an extract from Leah Purcell's play, The Drover's Wife. If the class is not reading the whole play, the teacher may need to summarise the story for students - especially to the point where the extract starts. Once students know the general story, the teacher provides a summary of the extract: 'Yadaka has been taken to a mission by a priest named Father Matthew. However, he does not find that life in the mission gives him a sense of closeness to his homeland, and so he leaves. He walks, by himself, into the Snowy Mountains where he meets other groups of Aboriginal people who are gathering for celebrations associated with the summer return of the Bogong moth to mountains. During the celebrations, he is attracted to a beautiful woman and stays with her group.'

Once students have a general overview, read the extract closely. A PDF lesson plan has been provided to undertake a detailed reading (of the type recommended in Reading to Learn pedagogy).

As a class, discuss the following, levelled questions:

- What details about the country of Great Diving Range is included in Yadaka’s description? (literal)

- What words can be used to summarise Yadaka’s representation of this country? For example, is the country represented as desolate, bleak and empty? (inferred)

- What cultural assumptions, values and beliefs underpin Leah Purcell’s The Drover’s Wife? (interpretive)

-

This activity continues to examine how Aboriginal writers represent the land, with a focus on Yankunytjatjara/Kokatha woman, Ali Cobby Eckermann. Here, we will examine Text 2 above, Eckermann's poem, 'Birds', from her verse novel Ruby Moonlight (a novel of the impact of colonialism in mid-north South Australia around 1880). Again, teachers should provide students with a brief summary of the context leading up to the poem, i.e. a massacre has occurred and the sole survivor, a woman (the 'she' of the second line of the poem), is 'shattered by the loss' and stumbling through the landscape. In small groups, read the poem aloud a few times, experimenting with different ways of reading the lines and discussing how to perform the words 'trust nature'. For example, students should discuss:

- Why these words are justified to the right? Why they are in a smaller font? Perhaps it suggests the words are whispered?

- Is the 'speaker' of those words the same as the speaker of the rest of the lines?

After watching and discussing different performances, focus on reading the text more closely with an emphasis on:

- Structure - the first and last stanzas focus on the actions of the woman; the remaining stanzas (excluding the line 'trust nature') focus on the activity of the birds.

- Language use -

- focus on the significance of the the difference between the doing verbs associated with the woman* (staggers, turns, follows) and the birds (i.e. lead, place, flit, nest, turn x2, lay, flutter, flicker, stand) [*Note in the first line, the verb 'shattered' is used in conjunction with the Actor (or subject), 'senses'. Depending on your interpretation, 'shattered' could be a doing verb or a thinking verb.]

- the significance of the repetition of the clause 'trust nature'. It is written as an instruction (the verb comes first in the clause), so consider who is instructing whom.

Finally, as a group consider the values and beliefs about nature that underpin Eckermann's poem. [She represents nature and humans as having a close relationship, one where nature can be relied on for protection and help.]

-

So far, we have explored two texts by Aboriginal authors which represent land and Country as a vibrant and mutually nurturing. In this activity, we turn our attention to Waanyi man Gordon Hookey's perspective on white invasion and the very different attitude towards land which colonisers brought with them from England.

Before reading an extract from the interview, for context teachers might like to show one or two short YouTube videos of Hookey discussing his work: talking to art students at GOMA in Brisbane [note: the audio is good, but the focussing on the video is poor] and painting and talking about his work, Murriland #2. Even if the videos are not shown, it is worth foregrounding a couple of points:

- while Hookey's work is about truth and honest and he is a serious artist, he also emphasises that his work involves joking, laughing and playing as well

- the interview deliberately avoids what has been called the 'white gaze', i.e. the tendency to see and interpret the world through perspective of (racialised) white culture. As Stan Grant has pointed out, the white gaze 'traps black people in white imaginations' (see Chapter 5 of his book Australia Day from 2019).

In addition, students might need some background on the legal term terra nullius, and the declaration by Lieutenant James Cook (acting against official orders) that the Australian continent was an 'empty land' or 'land belonging to nobody'. This declaration opened the way for the invasion and settlement of Australia, and the accompanying dispossession and oppression of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples which continues to this day.

Read the interview extract and then, in small groups, students can discuss the following questions:

- How does Hookey play with the term terra nullius - in two different ways? In what ways does this wordplay (the creation of a neologism) position Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in new/different ways from what a reader might be used to?

- Highlight Hookey use of pronouns such as they, us, we, me; use different colours for pronouns associated with settlers and Aboriginal Peoples (including himself). What pattern emerges? How is this pattern significant, i.e. how are they used to create different affiliations, or senses of community?

- In 'Birds', Eckermann says 'trust nature'. However, in this interview Hookey warns of the land striking back. How can both those views of Country be reconciled?

- What are Hookey's key messages?

- Looking back at the three texts examined so far, how are the underlying attitudes values and beliefs both similar and different?

-

By now, students should have developed an understanding of how Aboriginal writers and artists represent the land/Country and the underlying attitudes, values and beliefs. [Teachers might want to examine further texts, writers and artists before moving on.] Having centred these texts, we will now turn to a colonial text, Henry Lawson's short story, 'The Drover's Wife', a text that was used by Purcell as a springboard for her play. You might like students to read her 'Writer's Note' at the beginning of the play either before or after reading Lawson's version.

Students should read Lawson's whole story and then undertake a close reading of key extracts (for example, see Text 4 above). To complement the detailed reading activity for Purcell's The Drover's Wife, a detailed lesson planner (inspired by David Rose's Reading to Learn pedagogy) has been developed for the Orientation of Lawson's story. Students will need their own double-spaced copy of the extract, as well as a highlighter.

If you do not use the planner provided, a couple of points are worth drawing to students' attention:

- The term 'bush' which now seems a very 'natural' label for Australians to use actually carries ideological and colonial baggage. According to the website etymonline, the meaning of 'bush' is: outside urban area; unique landscape, very different for Europeans; first used in British American colonies from 1650s for an ‘uncleared district’ (in South Africa it was used by colonisers and settlers for an ‘uncultivated district’).

- The common sheoak (used by Lawson as the one thing in the landscape to 'relieve the eye') was used for a number of purposes by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples according to the National Botanical Gardens: the wood was used for boomerangs, shields and clubs, young shoots were chewed for thirst, and young cones were eaten. However, there is no evidence that Lawson was aware of this.

After close analysis of the extract, students should consider the following, levelled questions:

- What details about the landscape are included in the Orientation? (literal)

- What patterns of language are identifiable in the text? (inferred)

- How are readers positioned to think about the Australian landscape? (interpretive) In answering this question, students can start making informal connections among the Lawson text and the Aboriginal-authored representations of land/Country from Activities 1, 2 and 3. [Activity 5 will continue this in a more formal way.]

Extension: Find, engage with and explore Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories in which snakes feature. Besides stories about the Rainbow Serpent, read others such as the D'harawal Dreaming story, 'Bah'naga and Mun'dah: The Story of How the Red Bellied Black Snake Came to Be'. Compare their representations with that of the snake in the Lawson story. -

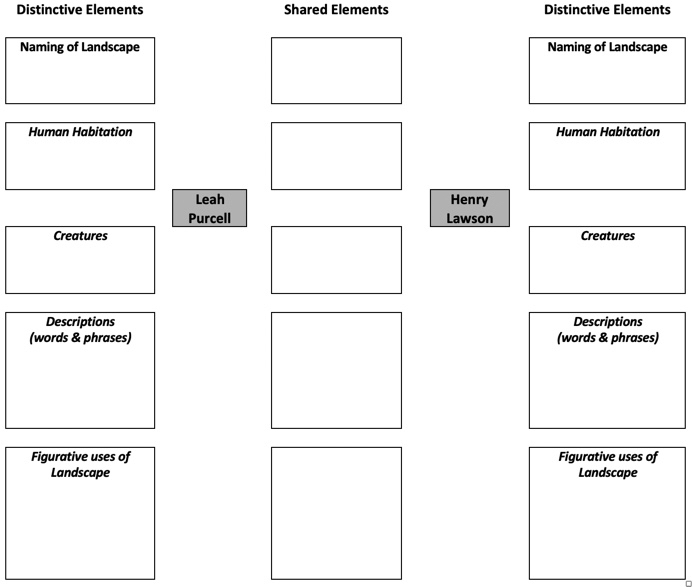

The purpose of this activity is for students to make a more formal comparison of representation of land/Country in Leah Purcell’s and Henry Lawson's versions of The Drover’s Wife. During the previous activities, students should have identified key words and phrases (including as similes, metaphors) used within the respective texts.

Now, using the double map below, synthesise how the land/Country is represented in the two texts. Some interpretation/summary may be required for the sake of brevity. (Click in the top left-hand corner of the map for a larger image.)

-

After the double bubble map has been completed, in small groups students should discuss:

- How do representations compare? What is similar and different?

- What underlying cultural assumptions, beliefs, attitudes and beliefs are revealed by this comparison?

- To what extent does Lawson 'encode' (probably unconsciously) the concept of terra nullius?

- What key messages can we take away about reading and writing about The Australian landscape and Peoples?

A completed double bubble map is available for teacher reference. Note: The answers for the Purcell text include evidence from across the whole extract (Text 1 above) and not just the portion examined in detail in Activity 1.

-

The next couple of activities are designed to demonstrate other, possible pathways a unit based on Leah Purcell's The Drover's Wife could take.

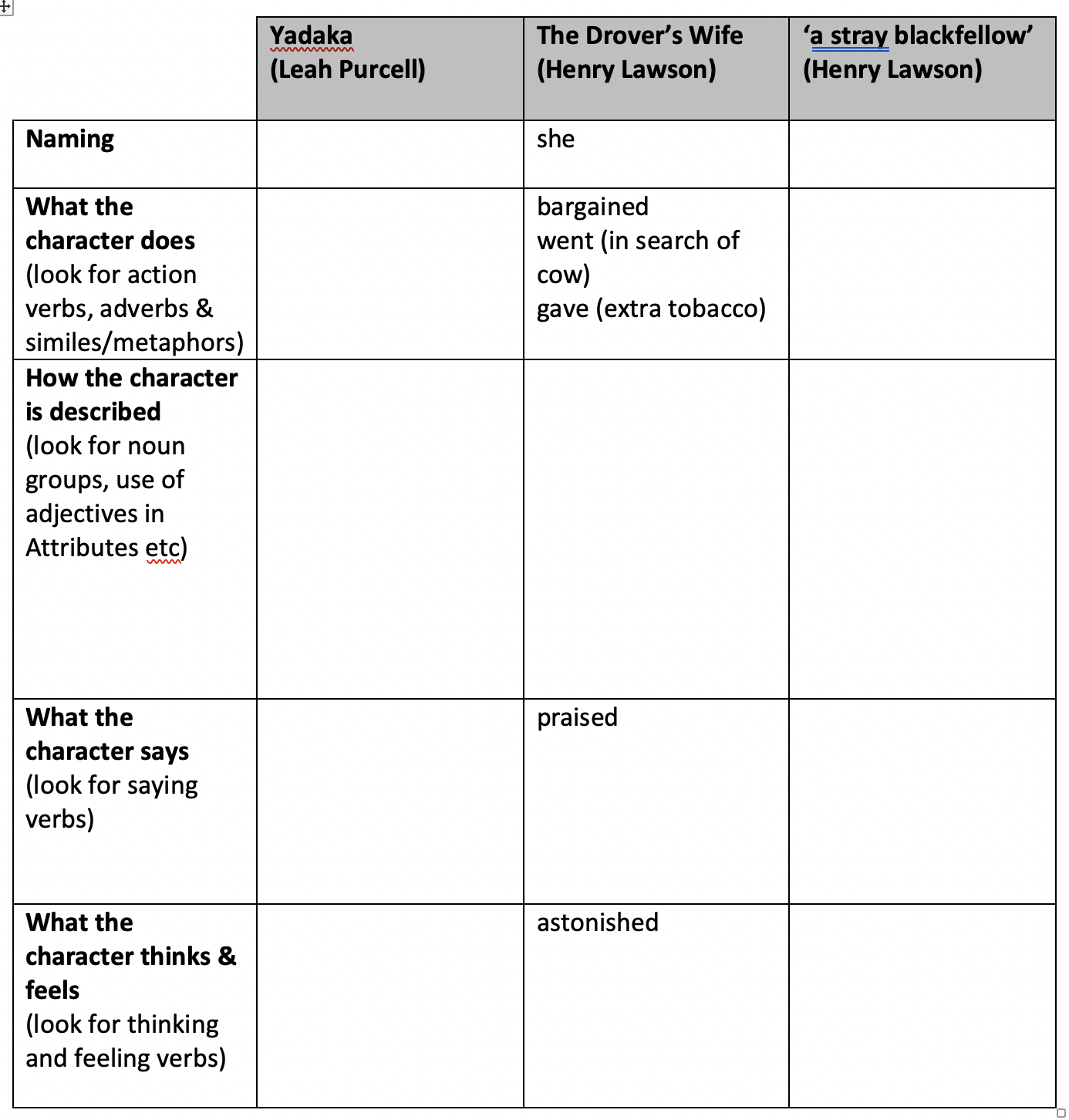

Using the table below, compare the construction of Aboriginal characters in the extracts provided from Purcell and Lawson versions of the story. For comparison, the centre column contains words and phrases used to construct the character of the Drover's Wife in the Lawson version. (Click in the top left-hand corner of the table for a larger image.)

Before beginning, it might be worth discussing Lawson's use of the term 'stray' - not a word normally associated with people. Consider this use in conjunction with Gordon Hookey's observation (Text 3 above) that the concept of terra nullius 'meant they [the colonisers] saw Australia as uninhabited; basically, they saw us as animals'. -

A completed retrieval chart with suggested answers can be found here.

When completed, students should discuss:

- What (mini)patterns do you notice?

- Based on the extract of the play that you have examined, how has Purcell given voice and agency to Yadaka?

- How do the representations of Aboriginal Peoples in the Purcell and Lawson versions differ, e.g. with regard to voice and agency?

Students could continue to examine these representations across the whole of both texts. -

In the previous activity, students will have realised how thinly Lawson develops the 'stray blackfellow' (see discussion of the epithet 'stray' in Activity 6). The purpose of this activity is to try to 'activate' this character, making him a more three-dimensional character with voice and agency.

Students should try to rewrite the ‘stray blackfellow’ extract using the following guidelines:- give the character a name (not an Anglo one!)

- provide him with dialogue, e.g. does he have a reason for stacking the wood hollow?

- give us an insight to his internal feelings and thoughts, e.g. does ‘head erect and chest held out’ mean he was proud of the remark, or trying to maintain his dignity in the face of the wife’s patronising and infantilising remark?

- remove the doubt cast on his character with the use of ‘but’ in the final sentence.

The teacher will need to monitor the work closely to ensure the development of positive characterisations.

-

Based on the activities suggested above, consider the following questions:

- What additional texts by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander authors could be used as a part of this classroom activity sequence?

- What evidence is there to support Julianna Schultz’s claim that ‘the old [colonial] stories have also become threadbare, and increasingly fail to capture the contemporary reality or complexity of the past’?

- What questions, issues, challenges or opportunities do these activities raise for my own classroom and English units?

- What more do I need to learn? Where can I learn this? How can BlackWords help English teachers contribute to a more just Australian society?

- What three specific actions can I take in a current unit to improve the representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander texts, voices and perspectives?

- What will be my indicators of success? How will I measure success?

-

As stated earlier, the purpose of these activities (and the accompanying workshop) is to open conversations, and point to a couple of fruitful areas that could be explored using these two versions of The Drover’s Wife. To finish, let me briefly suggest five other ideas that might add richness to an exploration of the texts.

-

1. Visualisation of the Character, the Drover’s Wife

Using a visual analysis framework, analyse two or more different images of the wife, e.g., Russell Drysdale’s painting, photographs of Leah Purcell performing on stage, and perhaps sketches of the wife illustrating printed versions of the Lawson story.

Consider: How are the representations similar and different? How do these representations position viewers (and readers) variously? In particular, discuss the choice in the Belvoir stage production for Leah Purcell, ‘a proud Goa-Gunggari-Wakka Wakka Murri woman’ (see author bio at beginning of Purcell 2016) to perform the role of the Drover’s Wife, who remains a white woman in the play.

Extension: compare the visual representation of Danny (the son) and Yadaka in the Belvoir production.

-

2. Character Construction and Agency

Compare the construction of key characters in the Lawson and Purcell versions. In particular, it is important to examine the Wife and Aboriginal characters in the two versions. With the latter, a key difference to consider is Lawson’s portrayal of the ‘stray blackfellow’ as the antagonist (he is the one who makes the woodpile hollow, providing a home for the snake and thereby setting in train the Wife’s terrifying night) as opposed to Purcell turning Yadaka into ‘the hero’ (Purcell 2016: viii).

Discuss what a difference it makes that all the characters are ‘activated’, to use Purcell’s word.

-

3. Comparing Plots

Summarise (e.g., on a timeline) the plots of Purcell’s play and the original Lawson story. Discuss the different uses of structure and story development, and their contribution to the overall messages of the stories. In addition, remember that an effective, emotionally engaging narrative contains both a plot line and relationship line, i.e., ‘stuff happens’ (the plot), but as it does, characters’ relationships develop and they undertake their own emotional journey. The relationship line(s) could be mapped alongside the plot line.

Extension: using the tableaux drama strategy (e.g. https://dramaresource.com/tableaux/), have students work in small groups to depict dramatically key scenes from the story, giving consideration to mood and emotion in the journeys of the characters.

-

4. An Australian Western

Purcell states that she thinks of this play ‘as an Australian Western for the stage’ (Purcell 2016: viii). Ask students to research the genre of ‘western’ and consider the links between this genre and Purcell’s play, e.g., how are the various conventions (including setting, language, archetypes, symbols, etc.) of the genre activated in the play and what is the possible significance of this for our interpretation of the play? What connection is there between Purcell’s construction of Yadaka and the racialised stereotype of ‘red injuns’ of the American western? How are conventions of the Western genre used and subverted by Purcell?

-

5. Culminating Activities

Have students complete an extended response to the play. Here are a couple of suggestions (including one that meets the syllabus requirement of a written response for a public audience). Use AustLit’s BlackWords resources to help you prepare students for these tasks in informed, sensitive, culturally appropriate ways.

a. Analytical essay (Interpretation-style) genre: Leah Purcell’s The Drover’s Wife has been called ‘dangerous’ and ‘subversive’. How does Purcell’s construction of Aborignal characters contribute to this reading? In answering this question, compare Purcell’s characters to those in Henry Lawson’s original story, and include, if relevant, reference to other texts (including feature films) to support your interpretations.

b. Narrative (play): Find another settler colonial story featuring Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander characters. Write your own play script (or selected scenes) that subverts the original, infusing it with First Nations history and knowledge. Your information can draw on existing, publically available accounts of Australian Frontier history and, with the appropriate permissions, local family and community histories. AustLit can be a very helpful place to start.

Below are some example searches of material on BlackWords and AustLit, focusing on the kinds of materials in the lessons plans above. Clicking on these links will take you away from this page, but you can return easily by clicking on the back arrow on your browser.

BlackWords short stories

All stories / Stories with full textBlackWords poems

All poems / Poems with full textBlackWords drama

All plays / Drama with full textBlackWords short stories with teaching resources BlackWords poetry with teaching resources BlackWords drama with teaching resources -

Eckermann, A. 2012, Ruby Moonlight, Magabala Books, Broome (Western Australia).

Hookey, G. 2017, Summoning Time: Painting & Politikill Transition in MURRILAND!, Griffith University, Nathan (Queensland).

Lawson, H. 1985/1892, ‘The Drover’s Wife’, My Country: Australian Poetry and Short Stories Two Hundred Years, ed L. Kramer, Landsdowne Press, Sydney, pp. 198-204.

Purcell, L. 2016, The Drover’s Wife, Currency Press, Sydney.

QCAA 2017, English 2019 v1.1: General Senior Syllabus, Queensland Government, Queensland.

Schultz, J. 2017, ‘Stories We Tell Ourselves’, Griffith Review, no. 58, pp. 7-11.

You might be interested in...