AustLit

The material on this page is available to AustLit subscribers. If you are a subscriber or are from a subscribing organisation, please log in to gain full access. To explore options for subscribing to this unique teaching, research, and publishing resource for Australian culture and storytelling, please contact us or find out more.

As a little boy John Clarke lived with his parents and younger sister Anna, in Palmerston North in New Zealand. John’s mother, Neva, was a keen reader and writer. She encouraged her children to observe people and imagine what they were thinking and doing. This was before television and the kids grew up with radio, although Neva was interested in the theatre and music, too, and took Anna and John to concerts and plays. At the Opera House they saw performers as diverse as Joyce Grenfell ‘who was very funny’, and John Gielgud, ‘who was very serious’ Clarke recalls. John also saw a South African revue called ‘Wait a Minim!’ as a boy and thought it was exceptionally funny.

The New Zealand comic novelist Barry Crump was a favourite of John’s as a child. Neva took John with her to Crump’s house where he was delighted to meet the creator of the ‘blokey country yarns’. Crump’s writing captures the distinctive way men spoke to one another in New Zealand. His comic stories and the novel, Hang on a Minute Mate (1961) made a big impression on Clarke, who listened enthusiastically to the author reading his work on the radio.

At Scots College in Wellington, when John was 14, he discovered a cartoon in a history textbook. It was the famous David Low cartoon of Hitler and Stalin meeting, published in 1939, and he marvelled at Low’s unique manner of portraying evil.

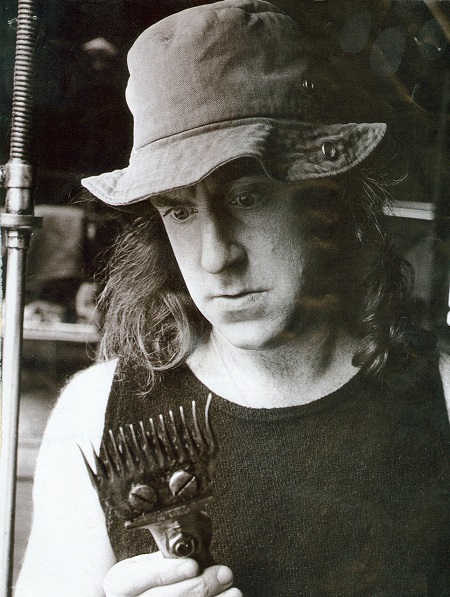

Clarke aged 10 at YMCA camp. Courtesy of John Clarke.

Clarke was struck by its boldness and clarity, the terrible context and dead Poland, the perfectly mannered stances of the two liars, and by the fact that Low had used their own words to do it. Years later Clarke would perfect in sketch comedy what he had seen in Low’s cartoons: telling a shocking political truth through humour, using the precise words of those in power to skewer them.

In the next few years Clarke spent some of his summers working on shearing gangs as a rousey and sometimes as a presser, his ears tuned to the colourful slang of all the men he encountered in the sheds. He started to think about the sheep farmers he met and imitated their speech to amuse his friends, sometimes giving short impromptu performances of these men. Still undecided about his future, he had enrolled in a Bachelor’s degree course in Arts and Law at Victoria University, where he gravitated to theatrical revue, and worked back stage in 1968, because he had heard there was free beer. In 1969 he was in the show.

Right from the beginning he seemed to have an instinct for emulating the distinct rhythm, cadence and lexicon of New Zealand English, and a firm grasp of comic timing. A year later he began writing and performing regularly (with John Banas, Ginette McDonald and Paul Holmes) in a semi-professional popular late night sketch show at the Downstage Theatre in Wellington. Roger Hall, who had noted Clarke’s ability to devise comedy (he even used the words ‘comic genius’), then invited him to contribute to a new revue called One in Five (1971). The title referred to a recently announced finding that one in five New Zealanders suffered from mental health disorders. It was a ground-breaking revue, with Clarke’s ‘frightening realism’ in a sketch portraying a one-way telephone conversation to his mate “Trev” singled out by reviewers as a highlight.

In 1971 John left New Zealand to travel. He took a job as a van driver in London, travelled around Britain and read Private Eye. Later that year his friend Ginette McDonald, who was also living in London, talked him into auditioning for the young Australian director, Bruce Beresford, who was making a film in which a lot of young men were required. Clarke had never auditioned for anything (and still hasn’t: ‘I wouldn’t know what to do’ he says) and was enjoying his freedom and his afternoons in the pub. Ginette insisted, and telephoned the producer to make an appointment for him. John complied, and went to the audition.

When Clarke read from the script for The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1972) he roared with laughter, and was awestruck by the talent of the three men who were the driving forces behind the film: Bruce Beresford, Barry Humphries and Nick Garland. Garland, a New Zealander, had drawn the cartoons for the Barry McKenzie comic strip, on which the film they were making was based. During the filming period Beresford and Humphries shepherded Clarke along, and Don McAlpine let him look through the film camera, explaining technical details about how he planned to shoot, and where the edge of the frame was. John spent hours talking to Barry Humphries about what Humphries read as a young man. He had loved Beckett in particular, Humphries told him—and suggested Clarke start with the novel Watt (1953). The audacity of this gangly, longhaired, young Australian and his vivid humour struck Clarke immediately, and was to have a huge influence on Clarke’s evolution as a performer. Humphries performed for a world audience, and while they parodied the Australian cultural cringe, he and Beresford asserted their equality with everything and anything British at every opportunity.

During the filming, industrial unrest caused power cuts all over England, and many productions stopped altogether. However, the McKenzie producers simply hired a generator and kept filming. Nothing fazed Beresford and Humphries: ‘There was no pre-emptive buckle because of some sense that you come from nowhere’, Clarke recalls. John felt that he could be himself with these men; better still he could be himself in the film, appearing in the pub scenes singing and drinking with Bazza McKenzie who was played by the tall, thin, long-legged and gentle Barry Crocker. Being permitted to play himself was the key to Clarke’s performance style and his future as a satirist: not only did it offer him a strangely comforting armour, but it provided the perfect satirical weapon and a mode of directly addressing the audience.

Fred Dagg

In London John met Helen McDonald, who came from Melbourne, and had been studying art history, painting and printmaking. They returned to New Zealand together, and married in Wellington in 1973. Clarke made contact with some of his friends from the revue days who were now working in theatre and broadcasting. He and Tom Scott, the cartoonist, published the first and only issue of a magazine called Horse and by the end of the year Clarke had made his first television appearance as Fred Dagg.

With this appearance Clarke launched the inarticulate sheep farmer, a larger than life comic character, a version of whom had originally appeared in the earlier stage revue One in Five, and before that in his rambling attempts to amuse his friends at university. Fred Dagg would quickly come to hold a similar place in New Zealand’s national culture, as Bazza McKenzie did in Australia at the same time, during the Whitlam years.

But from the beginning Dagg’s world was far more benign than that inhabited by Humphries’ rude larrikin. Unlike Barry McKenzie, Dagg was widely accepted by almost everyone: even the Prime Minister, Robert Muldoon, sensing a golden television opportunity, requested a meeting with Dagg. Throughout 1974 and 1975, Fred Dagg regularly appeared in interviews with actual reporters on television in a real current affairs program (Nationwide) on New Zealand’s only television station. Clarke modelled the character on the men he had met in the shearing gangs during his summer holidays as a teenager. With his endearingly dishevelled sheep farmer, he pioneered a new dramatic form for television, and the character became an integral element of the current affairs program. Fred Dagg was an instant and hugely popular character in New Zealand and was the subject of a Country Calendar television “documentary” at the end of 1974 in which the whole genre of the popular program was gently parodied. Dagg is first filmed in the shower, where he is shown carefully washing his gumboots. Then the action moves to the breakfast table, where Dagg sits, his dark wavy hair cascading out from under his hat, alongside his ‘approximately’ six adult sons, all called Trevor. Like their father, the Trevors are all dressed in black singlets and flapping shorts, and their cigarettes burn away as they demolish brick size loaves of bread and whole bottles of milk in one sitting.

Fred Dagg also charmed Australian audiences on radio, after he was discovered by hosts Robyn Williams and Bob Hudson, who regularly played Dagg’s songs and monologues on their shows. Bob Hudson played Clarke's material on his show on the newly established radio station 2JJ in 1975, before Clarke came to Australia. Robyn Williams also played Clarke's sketches on his newly minted radio program called The Science Show. This indication that Fred Dagg might work outside New Zealand, did not register with John immediately, but the fact that he had a radio audience in Australia boosted his confidence. In 1977 Williams broadcast a lengthy 'interview' with Clarke/Dagg conducted in the toilets (for quiet) at the ANZAAS conference, called 'The Meaning of Life', satirising scientists. The 'interview' offered a challenge for Clarke who was pleased to be able to generate new material for both Williams and Hudson on radio. Both Barry McKenzie and Fred Dagg were children of the British satire boom of the 1960’s and their creators were influenced by the leading figure of that boom, Peter Cook. They were both explicitly theatrical and nostalgic creations who spoke in the exaggerated but recognisable idiom of Australians and New Zealanders.

John Clark as Fred Dagg

If there were models for Clarke as a writer at this time they were the American actor and columnist Robert Benchley, who said he was ‘not quite a writer and not quite an actor’, and the Irish humourist Flann O’Brien/ Myles na Gopaleen (Brian O’Nolan). Both O’Brien and Benchley worked through an invented character, as Clarke did with Fred Dagg. Clarke, who thinks of himself as a writer first and foremost, admires O’Brien’s sense of maintaining his authentic stance as an ‘enemy of cant and pretension’. After a few years, Clarke started writing imaginary interviews with Australian politicians. One of the first was an interview with Joh Bjelke-Petersen, the loquacious and divisive Premier of Queensland who, as Clarke recalls, ‘did idiotic things’. Bjelke Petersen, who referred to press conferences as ‘feeding the chooks’, veiled his chicanery and contempt for the citizenry with disdainful humour for two decades, until he was eventually tried for perjury over evidence he gave in a royal commission that linked his government with organised crime. Clarke wrote his imaginary interview with Bjelke-Petersen using the standard interview question often put to comedians, ‘When did you first know that you were funny?’ The assumption driving the ‘interview’ was that: ‘Bjelke-Petersen was a professional idiot. He knew what he was doing’ Clarke says. It was a subtle but potent satirical point. The interview was published in the Times on Sunday (March 1987). In a chance meeting with Peter Cook in Melbourne, Cook suggested that Clarke perform the interview. Clarke hadn’t thought of the interview as a performance piece, but Cook’s advice made sense to him. Soon afterwards he began performing ‘interviews’ on radio, teaming up with a presenter called Bryan Dawe. This imaginary interview format soon became Clarke’s signature comedic form, providing the framework for the mesmerising series of television interviews with politicians entitled Clarke and Dawe that soon followed.

Sketching Pollies

Clarke worked with Paul Cox on the screenplay for the film Lonely Hearts (1982), a highly original romantic comedy in which he made a brief and amusing appearance. He gradually drifted back into television and to his original game: sketch comedy and current affairs, writing and performing with Max Gillies and a team of performers. The Gillies Report (1984) was performed in front of a live audience, reviving a form in Australia pioneered by The Mavis Bramston Show in 1964. It was broadcast weekly and centred around the actor Max Gillies who played all the politicians of the day: Fraser, Hawke, Peacock, Menzies, Whitlam, Gorbachev, Thatcher and an alzheimic Ronald Reagan.

Clarke, who played a newsreader in the series, wrote all his news bulletins just before the program was recorded. Some of the sketches were light and whimsical, while others were dark and more biting in their satire. In the final episode, Clarke appears at intervals wearing long effeminate wigs that become bigger, and more elaborate, in each scene. These segments were collated from the earlier episodes in the series. By the end of the episode the wig is a huge black and pink beehive and in the ultimate segment it morphs into a massive white cone out of which a Christmas tree pops. Clarke parodied the national obsession with sport, inventing a new imaginary sport called ‘farnarkeling’ and reported on Australian prowess in the sport regularly during the series. If the series favoured a hyper masculine style, offering its female actors Wendy Harmer and Tracey Harvey less opportunity to shine, it certainly recognised the problem in the culture and struck home in its parody of the super popular romantic game show Perfect Match.

The series was demanding and exhausting: in some episodes Clarke played eight characters and Gillies ‘anchored’ the show, daring to scorch his employer as he announced with mock gravity that ‘the Gillies Report shares the ABC’s obsession with quality, relevance and lack of unnecessary excitement’. If the show cemented Clarke’s insider status in Australia, and drew him back to his original form, it also set him thinking about a minimal style of acting that he preferred, one that is in stark contrast to that of Gillies, and relies on the actor’s own facial expression, voice and gesture rather than an impersonation of the politician who is the target of the satire.

Clarke disguises his acting by seeming to play himself, his nasal voice, laconic manner and blokey style a dimension of almost every role. It is an ingenious mask. This mask is also the way in which Clarke resolves the problem of drama as an actor, reconciling who he is through playing in a particular way. Every actor must do this and for Clarke a string of comic roles often coated with black humour provides that meeting of the actor and the acting. In the film Death in Brunswick (1990), Clarke, in clothes reminiscent of Fred Dagg, plays the gritty older mate, alongside Sam Neill’s character, the hapless, good-looking young chef, ‘Cookie’, who accidentally kills the kitchen hand. The film offers a rich blend of romance and grungy social realism, with much of its humour dependent on physical comedy that satirises masculinity. The darkness and violence of the film is balanced by the ridiculous comic situations.

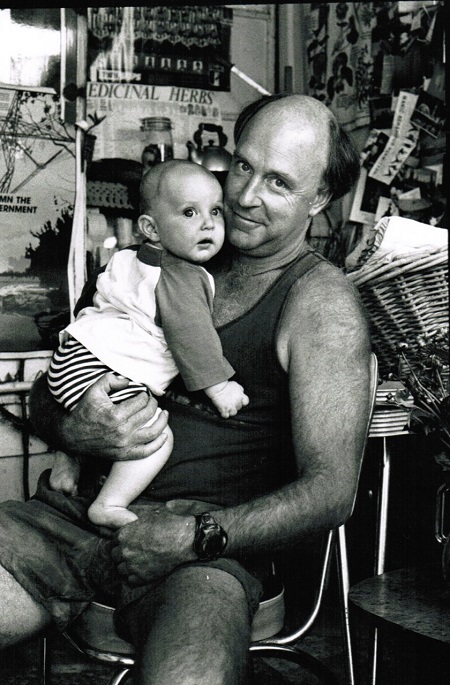

Clarke on the set of Death in Brunswick, 1990.

In Clarke’s television drama, The Games (1998, 2000) written with Ross Stevenson, a popular radio host and former lawyer, the writers experimented. Clarke recalls that ‘The idea was to shoot a satirical drama that appears to be a documentary so it looks real, only we’re monkeying with the visual grammar, we’re asking people to question the way they watch things; is it true because it looks true and if it isn’t, are the other things that look true actually or possibly false?’ Clarke invited Bryan Dawe, Gina Riley and Nicholas Bell to play his venal offsiders on the organising committee of the Sydney Olympics, creating a ‘delicious’ satire of the event on which the whole nation fixated for years before it happened. In keeping with Clarke’s style all of the actors used their real names.

The Games is one of the most significant Australian comic series ever broadcast, in which Clarke pioneered a new form of comic drama. The series lampooned the politics and personalities around the staging of the Olympic Games in Sydney, focusing on numerous real and imagined mishaps: the ticketing fiasco, corruption in the international movement, the ludicrous error of building the 100 meter track just 94 meters long, and the rank careerism of the planning authority officials—the show’s main characters. The inclusion of an apology to the Indigenous people of Australia by the actor John Howard appearing as the Prime Minister John Howard (never stating that he is the PM—he simply says ‘I’m John Howard’) in The Games is one of the most significant moments in Australian television history. The apology took aim at the fact that the real prime minister steadfastly refused to make an apology during his eleven years in office in spite of mounting public pressure to do so. The sequence offered audiences a touchstone for an era in a masterful comic intervention. Clarke wrote the script and John Howard created an astonishing portrait of political personality, and a razor sharp critique of hubris.

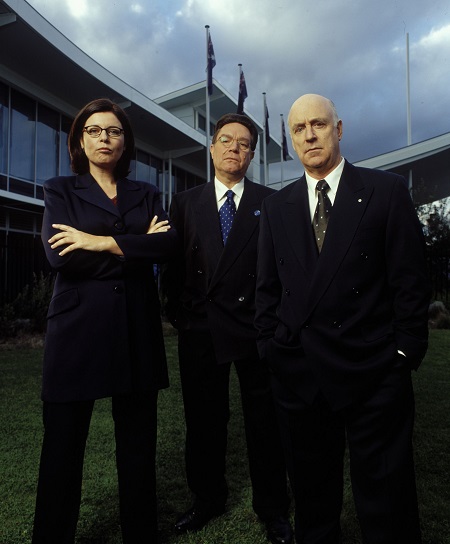

Riley, Dawe and Clarke in The Games, 1998

John Clarke and Bryan Dawe began performing their mock interviews on television in 1989. Clarke and Dawe relies on a parody of the primary political exchange of the television age: the political interview. The focus is squarely on the television theatre of politics and the peculiarities of each politician. The mock interview is compressed into two or three-minute episodes, each one revealing Clarke as a highly original performer who has perfected a distinctive form of sketch comedy. Both the form and the style of the mock political interview are unique to Clarke. He does not emulate the real figure he plays in the sketch. Without the distraction of mimicry the audience focuses on the words and the interaction of the two performers. But this is not simply verbal humour. The targets are spin and political arrogance. Although it originated in radio and migrated to television, in Clarke and Dawe facial and vocal expression, as well as gesture, are all-important. Clarke physicalises spin; his body carries the posturing of a range of political figures in each confected moment. His satirical wit relies on comic judgement and restraint, insight into political behaviour and a commanding performance style.

Clarke’s writing and his approach to acting have transformed sketch comedy. His comic gifts are presented to the audience as entertainment. But his comic sketches are a highly structured and nuanced form of satire; they are also a compelling element of the larger democratic project in which satire plays a glorious and vital part.

John Clarke died on 9 April 2017.

Clarke (left) and Dawe (right)