AustLit

-

This trail collects a range of items to enhance readers' engagement with Brumby Innes.

– Part One provides an overview of Brumby Innes, its author Katharine Susannah Prichard, and some background to the play's genesis.

– Part Two provides information on the play's prize-winning, initial reception and its long-delayed first production.

– Part Three focuses on the play's themes of landscape, sexual relations, race relations, and Indigenous culture.

– Part Four briefly places Prichard's play within the context of Australian drama in the first half of the 20th century.

– Part Five offers suggestions for wider reading.

– Part Six provides tips for further research.

Click on the hyperlinks below to visit AustLit records and external references. Some of the critical works and other resources are available online.

-

See full AustLit entry

See full AustLit entryBrumby Innes 'begins with a corroboree and, like Coonardoo, attempts to engage with a portrayal of Aboriginal life. Its central character, Brumby Innes, is a swaggering drunk who exploits the black workers on his station and abuses the women; he bears a close resemblance to Sam Geary in Coonardoo. Yet, Brumby Innes provides the central energy of the drama, and the celebration of that energy in the play conflicts with the dramatic critique of his sexism and racism.

(...more) -

See full AustLit entry

See full AustLit entryKatharine Susannah Prichard was born in Levuka, Fiji during a hurricane. (She was called 'The Child of the Hurricane' by the local population and used the name for the title of her 1963 autobiography.) Prichard grew up in Tasmania and Melbourne, and was educated at home until she was fourteen when she received a half-scholarship to attend South Melbourne College. Although she matriculated successfully, her mother's illness and the family's poverty made it impossible for her to pursue university studies.

-

In late 1926, Prichard spent two to three months at Turee Creek Station in Western Australia’s Pilbara region. Her intention had been to work on Haxby's Circus (completed later and then published in 1930), but instead she discovered the stories that would inspire three new works – the play Brumby Innes, the short story ‘The Cooboo’ (1927) and the novel Coonardoo (1928) .

In a letter to Vance Palmer and Nettie Palmer, written during her stay at Turee Creek, Prichard wrote: 'I've done a play to be called "The Brumby", or "Brumby _______" somebody or other. The real thing is here. His name is Leake. It fits so – "Brumby Leake". And I've got to find one that won't run me in for libel' (qtd in Lowe, Margot. 'Turee Creek.' Katharine Susannah Prichard Writers’ Centre website).

-

Turee Creek Homestead

Bill Day, a Research Officer for the Pilbara Native Title Service, visited Turee Creek in 2002 and provided this image of the station's homestead to the Katharine Susannah Prichard Writers' Centre.

-

'I’ve just finished two plays for the Triad affair. One a Nor’-wester which I suppose will be unproduceable ... it’s true in every word and detail ... I don’t in the least expect it to please anybody’ (Katherine Susannah Prichard in a letter to Vance Palmer, 23 June 1927; qtd in Throssell, Ric. 'Preface.' Brumby Innes, and Bid Me to Love (1974): ix).

-

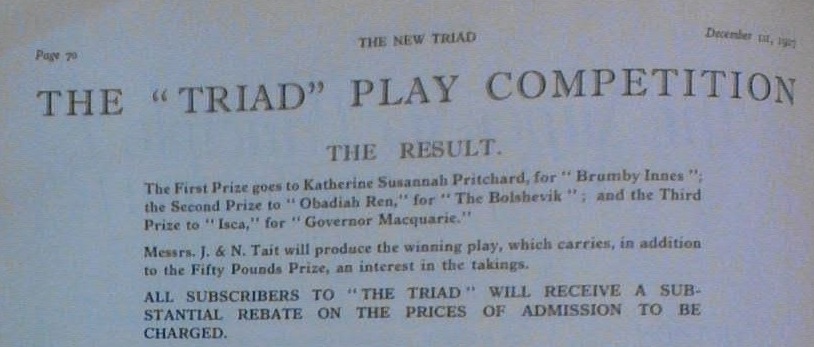

Prichard was only partly correct in her assessment of Brumby Innes. It was, at the time, unproduceable (see below for further information), but it did, initially, please some people. The play won the 1927 Triad Drama Competition for a three-act play. The New Triad, a revived version of the earlier Triad magazine, published the result of its competition in the December 1927 issue with the following opening remark from one of the judges, Gregan McMahon: 'I consider "Brumby Innes" to be in a class by itself. In originality of subject, atmosphere, characterization, virility and technique, it is a very remarkable work, comparable to some of the best of Eugene O’Neill’s, and it is, moreover, essentially Australian. It has been objected that the subject matter is sordid, and on that account the possibility of production should be discouraged. I am assuming that the subject matter of the plays presented is no concern of the judges; it matters not whether it be sordid tragedy or bedroom farce. We are looking for an Australian playwright who has the gift and technique of playmaking, who can at the same time work with facility in a purely Australian atmosphere, and from whom, in the future, work of a high standard may be expected (70).

-

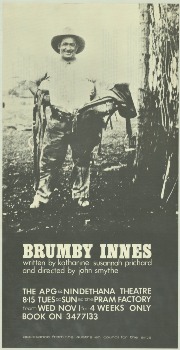

Despite the original plan for Brumby Innes to be produced by the J. and N. Tait theatre company, it was not performed until 1972 – three years after Prichard’s death. One possible reason for the delay is that the cast of 15 includes 11 Indigenous characters. John Smythe, who directed the premiere season at Melbourne's Pram Factory (following the play's re-discovery by Factory collective member Margaret Williams), suggests that the Factory's 'youthful arrogance ... stood us in good stead. It didn’t occur to us that we couldn’t do it' ('Pram Factory Recollections.', Pram Factory website [n.d.]). The production used a combination of two companies – the Australian Performing Group and the recently formed Indigenous theatre company Nindethana Theatre Group.

The production 'was so successful that a grant was sought and received to film the production. It was filmed at Channel 0 (now Channel 10) and went to air in June 1973 ... One result of the television production was that Koori members of the cast were picked up for other television productions' (Casey, Maryrose. Creating Frames: Contemporary Indigenous Theatre: 1967-1990 2004: 63-64.).

For a detailed review of the 1972 Pram Factory production, see Margaret Williams's 'Natural Sexuality: Katharine Prichard's Brumby Innes', Meanjin Quarterly 32.1 (Autumn 1973): 91-93. See also Maurice Dunlevy's review, 'A Brutal, Vital Bit of Theatre', in which he concludes: '‘Some critics have lamented that the play wasn't performed in 1927 when it was written. Personally I think it has found the perfect moment in 1972, with the place of Aborigines and women in Australian society now genuine public issues' (The Canberra Times (25 November 1972): 12).

-

Pram Factory Program, November 1972

The image (at left) shows the front of the Pram Factory's program for the 1972 production of Brumby Innes. The verso of the program includes full production details, together with background information on the Australian Performing Group and the Nindethana Theatre Group.

The program has been digitised by the State Library of Victoria and can be viewed here.

-

'What excited me about this play was that it got to the heart of all the issues – sexism, racism, class injustice and rape of the environment – by accurately observing what was so ... then leaving the audience to come to terms with it in their own way. As a piece of political theatre it could not have been more powerful' (Smythe, John. ‘Pram Factory Recollections.’ Pram Factory website [n.d.])

-

In his 1985 criticism 'Another Planet: Landscape as Metaphor in Western Australian Theatre', Bill Dunstone writes that, in plays like Prichard's Brumby Innes and Henrietta Drake-Brockman's Men Without Wives: A North Australian Play (1938), 'the alienating influence of the modern city ... is both thrown into relief and reflected by the ambivalent European response to the non-urban North Western Australian landscape. In Brumby Innes in particular, the settlers’ attempts to impose their material and utilitarian realities upon the environment bring them into conflict with the aborigines, whose spiritual and social ties with the land are a touchstone for European transience and alienation’. In Dunstone's view, 'the tendency in much Western Australian drama to displace urban crises into remote places while retaining a sense of their contemporaneity and immediacy is ... dramatically and sociologically significant (European Relations: Essays for Helen Watson-Williams (1985): 67-68, 69).

Viewing landscape through the prism of women writers' interpretation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Helen Thomson, in 'Gardening in the Never-Never: Women Writers and the Bush', emphasises the sense of sisterhood shared by the writers and Indigenous women. 'Imperfect though it may be', that sisterhood 'was expressed most powerfully through a shared, benign relationship with the natural world, in contrast to the exploitative violence of men’ (35-36). Thomson acknowledges, however, that the Indigenous landscape portrayed by writers including Prichard, Jean Devanny, Jeannie Gunn, Henrietta Drake-Brockman, Mary Durack, Eleanor Dark, Rosa Praed, Mary Gilmore and Catherine Martin was 'a site of paradoxical signification’ (22). (Thomson's article appears in The Time to Write: Australian Women Writers 1890-1930 (1993): 19-37.)

-

Women Writing the Landscape

-

Katharine Brisbane, in her introduction to Currency Press's 1974 publication Brumby Innes, and Bid Me to Love declares: 'Brumby Innes was half a century ahead of its time in the values it gives to romance and sexuality’ (xxv). Margaret Williams agrees with the emphasis on male/female relationships: 'It seems to me ... that Brumby Innes is not first and foremost about white exploitation of black, but about the nature of sexual relationships, and is really a hard-headed demolishing of the whole concept of romantic love as a basis for sexuality' ('Natural Sexuality: Katharine Prichard's Brumby Innes.' Meanjin Quarterly 32.1 (Autumn 1973): 92).

This theme is pursued by Jack Beasley in A Gallop of Fire: Katharine Susannah Prichard: On Guard for Humanity: A Study of Creative Personality (1993). Beasley argues that Brumby Innes has dual themes: 'human sexuality, sans chivalry and romance' and the exploitation of Indigenous Australians (75). Beasley further contends that Brumby Innes marks a watershed in Prichard's writing. His contention is that, during the 1920s, much of Prichard's work is ‘conceived and expressed in terms of deep sensuality’, with men drawn in ‘heroic proportions’ (76-77). But, in Bid Me to Love – the other play Prichard submitted for the 1927 Triad competition – the author signals that 'there would be no more celebration of Red Burke/Brumby Innes dominant male characters, nor would there be again the woman as a subordinate and dependent figure’ – instead, Prichard discovered 'her version of the eternal triangle which gave her the company of characters and the relationship between them which would be at the core of almost all her subsequent work' (80).

For further examinations of the sexual relations portrayed in Brumby Innes, see: Robert Sellick's 'Prichard, Brumby Innes and the Frontier' in (Un)common Ground: Essays in Literatures in English (1990): 75-83; and, D. Biggins's 'Katharine Susannah Prichard and Dionysos: Bid Me to Love and Brumby Innes' in Southerly 43.3 (September 1983): 320-331). Note particularly Biggins's argument that the two plays 'gain expressive force through their representation of primitive or elemental sexuality by means of elements derived from classical myth’, particularly associations with the Greek god Dionysus (321).

-

In 'The Politics of Race and the Possibilities of Form in the Work of Katharine Susannah Prichard' (Frank Hardy and the Literature of Commitment (2003): 185-197), Delys Bird discusses the 'inequities of power that structure race relations' on the Pilbara station and the expropriation of Indigenous labour 'by a Western utilitarian economic system' (193). Bird notes that the late 1920s (quite independent of Prichard's writing) witnessed the beginnings of 'a widespread and long-lasting public debate ... on the Commonwealth Government’s responsibility towards Australia’s Indigenous population’ (186). That debate was 'largely triggered by two major incidents': the Onmaleri massacre in 1926, and the murder of a prospector in the Northern Territory in 1928. (A fictionalised account of the massacre appears in Randolph Stow’s To the Islands.)

Another article reflecting on this coincidence of events in Australian politics and culture is J. J. Healy's 'Recovery' (Literature and the Aborigine in Australia 1770-1975 (1989): 139-153). Healy points out that Australians were not widely receptive to a public debate on Indigenous questions in late 1920s and early 1930s. As Healy details, the The Bulletin was reluctant to publish Vance Palmer’s Men Are Human in 1930. Bulletin editor S. H. Prior told Palmer that 'our disastrous experience with Coonardoo [Prichard's award-winning novel] shows us that the Australian public will not stand stories based on a white man’s relations with an Australian Aborigine' (qtd in Healy, 140). What is remarkable, for Healy, is Prichard’s ‘creative insight’ in Brumby Innes in moving into ‘a new field of Australian experience. She did it in advance of any signalling from her society, and in defiance of its restrictive prejudice’ (140).

-

The opening scene of Brumby Innes features a corroboree. Although, as Robert Sellick points out, Prichard 'lacked the expertise of the professional anthropologist', she was still 'groping towards an understanding of the sacred-secret nature of ritual and language and the significance of ceremony in Aboriginal society' ('Prichard, Brumby Innes and the Frontier.' (Un)common Ground: Essays in Literatures in English) (1990): 76).

Sue Hosking, in 'Two Corroborees: Katharine Susannah Prichard's Brumby Innes and Mudrooroo's Master of the Ghost Dreaming.' Myths, Heroes and Anti-Heroes: Essays on the Literature and Culture of the Asia-Pacific Region (1992): 1-19), also focuses on the corroboree. Hosking says that Brumby Innes 'represents one of the most significant early attempts by a non-Aboriginal Australian to acknowledge the value of Aboriginal presence in the struggle to bring into focus a land ... perceived at the time to be newly occupied’ (12). While stating that Prichard's 'observing self' is 'laden with cultural baggage' (13), Hosking notes the writer's attempt to connect the character of Brumby Innes to the Indigenous mythological figure of Narloo (14). ‘Prichard’s understanding of Aboriginal culture, and most particularly of Aboriginal sexuality, may be limited and confounded by idiosyncratic beliefs. Yet her text at least embraces Aboriginal Australians in the construction of an Australian identity’ (15).

-

'In the period 1900 to 1960 in particular, tragic conflict is a recurrent element in almost every significant Australian play'. It occurs in 'much of the work of Louis Esson [and] in the best plays of newly important women writers like Katharine Susannah Prichard (Brumby Innes) and Betty Roland (The Touch of Silk) …' (Sturm, Terry. 'Drama.' The Oxford History of Australian Literature (1981): 206-207). Sturm details Prichard's place in Australian theatre history and provides further insights into Brumby Innes in the course of his overview (pp. 175-267).

Prichard's son Ric Throssell believes that his mother's 'contribution to Australia drama ... has its place in the stream which leads to the great spring flood of Australian dramatic writing in the seventies'. For more about Prichard’s seventeen plays, see Throssell’s preface to the Currency Press publication, Brumby Innes, and Bid Me to Love (1974): ix-xviii. For more on the ‘spring flood’ of the 1970s, see Maryrose Casey’s ‘Australian Drama Since 1970’ in A Companion to Australian Literature Since 1900 (2007): 219-232.

See also: 'Dramatic Writing in Australia', an article by Nettie Palmer in 1928 that places Brumby Innes within the context of the Repertory Theatre movement in Australia (Illustrated Tasmanian Mail (4 April 1928).

-

- Prichard was a founding member of the Communist Party of Australia. From 1919 onwards, as a result of her political allegiance, she was the subject of government security surveillance. Fiona Capp, in her column 'ASIO's Writers Clamp' (Sydney Morning Herald, 15 April 1988: 68), details the experiences of Australian writers who were 'thought to be potential subversives'. The files on these writers, says Capp, reveal a 'wholesale paranoia about writers in Australia'. The 'most apparent reason' for suspicion was 'association with the Communist Party ... But Soviet connections, membership of the Australian Council for Civil Liberties, the Australian Peace Council, the Fellowship of Australian Writers or the Realist Writers Group, also inspired suspicion.' Capp outlines the extent to which Prichard was 'persecuted, but never prosecuted, by the authorities' and the effects of this surveillance on her literary career.

- To understand more about the reasons for Brumby Innes's non-production until 1972, see Julian Meyrick's The Retreat of Our National Drama (2014). Meyrick argues that 'for most of our history it has been easier for foreign playwrights to find a place in our repertoire than Australian ones. This was the result not of a young country hesitantly feeling its way to theatrical confidence but the opposite: of a sector that grew too rapidly, too successfully and with too much vertical and horizontal integration; an industry that grew with its heart outside its body, self-estranged and self-displaced; a nation’s theatre with a nation’s drama excluded' (44).

- For further background on Prichard’s portrayal of the Ngarla people of Western Australia, see Carl von Brandenstein’s Notes on the Aborigines in Brumby Innes' and 'Glossary of Aboriginal Words in Ngaala-warngga occurring in Brumby Innes, and Bid Me to Love' (1974): (101-107).

- Detailed information about the Ngarla people, including their languages, history and culture, is available via the website of the Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre.

- 'Until the 1960s there were no plays written by Australian Aborigines that were produced. Until then there were also only minor roles written for indigenous people in theatre. There were certain archetypal Aboriginal characters but mostly played by white actors wearing "black face", make-up that darkened their complexion' ('Cl@ssmate series 13 - #5 - Aboriginal Dance.' Daily Telegraph 5 March 2013: 34. To learn more about the use of 'blackface' in Australian films, see Andrew Pike's 'Aboriginals in Australian Feature Films.' Meanjin 36.4 (December 1977): 592-599.

-

- There is additional information in AustLit aboutKatharine Susannah Prichard and Brumby Innes – follow the links within Katharine Susannah Prichard's author record and the record for Brumby Innes to explore more.

- To further investigate topics such as critical articles dealing with 'Sexual life & gender relations - Literary portrayal' or 'Aboriginal Australians - Literary portrayal', go to the AustLit search page and explore the Advanced Search options. For help on building searches, visit the 'How to Search AustLit' page.

- Visit the website of the Katharine Susannah Prichard Writers' Centre to find out more about Prichard's legacy in Western Australia. For details on her 11 Old York Rd, Greenmount home (which, in turn, became the writers' centre), see Western Australia's Heritage Council website and also the entry for 11 Old York Rd on the 'Register of Heritage Places'. (The latter details are accessed via the National Library of Australia's Web Archive, PANDORA.)

- Prichards papers are held at the National Library of Australia. The papers include letters relating to the publication and reception of her works in the former U.S.S.R. and to her literary life in Australia.

- Prichard's husband Hugo Throssell was awarded the Victoria Cross 'for most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty during operations on the Kaiakij Aghala (Hill 60) in the Gallipoli Peninsular on 29 and 30 August 1915' ('Second-Lieutenant Hugo Throssell.' Gallipoli and the ANZACS website.) Prichard met Throssell in London after he was wounded in the action at Hill 60. Throssell's biography in the Australian Dictionary of Biography records Throssell as claiming 'that the war had made him a socialist and a pacifist. The combination of [Prichard]'s award-winning novels and Communism, and his Victoria Cross, brought them fame and notoriety.' The action for which Throssell was awarded his Victoria Cross has been dramatised in the 2010 film Beneath Hill 60.

-

'Katharine's Place'

Prichard and her husband Hugo Throssell purchased the home at 11 Old York Rd, Greenmount, in 1919/1920. 'Katharine's Place was the name Katharine Susannah Prichard's friends gave to the Australian author's Greenmount home. When the KSP Foundation was established in 1985, it was decided to retain this already recognised name. Now also known as the Katharine Susannah Prichard Writers' Centre, the oldest writers' centre of its kind in Australia, the house is a familiar meeting place for writers of all persuasions.' (Extract from Katharine Susannah Prichard, Her Place, researched and compiled by Pam Portman and Sally Clarke. Further extracts appear on the Katharine Susannah Prichard Writers' Centre website.)

You might be interested in...