AustLit

-

This trail collects a range of items to enhance readers' engagement with Such Is Life.

– Part One provides an overview of Such Is Life and its author, Joseph Furphy (aka 'Tom Collins').

– Part Two focuses on the revision, publication history and reception of Such Is Life.

– Part Three looks at the structure of Such Is Life.

– Part Four highlights aspects of Furphy's novel including literary allusions, and nationalism and nation-making.

– Part Five offers suggestions for wider reading.

– Part Six provides tips for further research.

Click on the hyperlinks below to visit AustLit records and external references. Some of the critical works and other resources are available online.

-

See full AustLit entry

See full AustLit entrySuch is Life: Being Certain Extracts from the Diary of Tom Collins. Joseph Furphy's title gives an indication of the complexity of the narrative that will unravel before a persistent reader. In chapter one, the narrator, Tom Collins, joins a group of bullockies to camp for the night a few miles from Runnymede Station. Their conversations reveal many of the issues that arise throughout the rest of the novel: the ownership of, or control of access to, pasture; ideas of providence, fate and superstition; and a concern for federation that flows into descriptions of the coming Australian in later chapters.

(...more) -

See full AustLit entry

Joseph Furphy was born at Yering, Victoria, in 1843, the son of Protestant Irish immigrants. Furphy was educated primarily by his mother from whom he inherited a love of literature. In 1867 he married Leonie Germaine with whom he attempted to work a selection in the Lake Cooper district. After selling the selection and purchasing a bullock team in 1873, Furphy moved to the Riverina in New South Wales and started a carting business. This business endured until the drought of 1883 drove Furphy bankrupt.

-

Joseph Furphy's Home in Shepparton, Victoria

'When Joseph Furphy returned from the Riverina to Shepparton he lived in a house in Welsford Street, the back of which faced the River Goulbourn. Here, in a small room at the front right of the picture he wrote his book Such is Life.'

This information appears on a typed sheet attached to the back of a photograph held by the State Library of Victoria. The photograph was taken in 1938 by John Kinmont Moir.

-

Julian Croft draws attention to Furphy's choice of title and pseudonym for his novel. Croft says: 'The pen name Furphy chose had a special significance. In Australian bush slang of the time Tom Collins was usually blamed as the source of all rumor, and the name became synonymous with unreliability and distortion of the truth. In titling his novel "Such Is Life" (itself a traditional phrase of stoicism and reputedly the last words of Australia's most famous criminal, Ned Kelly) and crediting it to the authorship of Tom Collins, Furphy was indicating that this supposedly realistic account of life in the backblocks should be taken with a grain of salt, and ironized salt at that.'

'Joseph Furphy.' Australian Literature, 1788-1914. Ed. Selina Samuels. Detroit: Gale Group, 2001. Dictionary of Literary Biography vol. 230.

-

Joseph Furphy to The Bulletin editor J. F. Archibald, 4 April 1897: 'I have just finished writing a full-sized novel, title, Such is Life, scene, Riverina and Northern Vic; temper, democratic; bias, offensively Australian ... I am, Sir, Yours very truly, Joseph Furphy (Tom Collins).'

Archibald deputises The Bulletin's 'Red Page' editor A. G. Stephens to correspond with Furphy. On Stephens's advice, Furphy quickly provides a copy of his 1,125 page manuscript for assessment.

Stephens to Furphy, 25 May 1897: the book is 'fitted to become an Australian classic … But I do not think it would find a quick sale, or an extensive sale.' (Reproduced in: Franklin, Miles and Kate Baker. Joseph Furphy: The Legend of a Man and His Book. Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1944: 50, 52.)

Stephens is correct on both counts – and nor would the book find a quick road to publication. Six years, and extensive revisions, later, Such Is Life is published in August 1903.

-

On the advice of A. G. Stephens, Furphy thoroughly revised his 'Such Is Life' typescript in 1898 and again in 1901. In the process, he deleted two original chapters. Both excised chapters were later published independently: chapter five became Rigby's Romance: A Made in Australia Novel (serialised, 1905-1906; published in book form, 1921) and chapter two became The Buln-Buln and the Brolga (1948).

In the years following eventual publication in 1903, Stephens's initial insight proved prescient. Such Is Life sold 250 copies over 12 years. Furphy's devoted friend Kate Baker purchased the 'uncut pages of the remainder of this edition' and had these copies published in 1917 with the addition of a preface by Vance Palmer (Ewers, 34). An abridged edition was published in London by Jonathan Cape in 1937. In 1944, Jonathan Cape and Angus and Robertson jointly published a new edition; this unabridged edition has been used regularly to offset further reprints and additional versions from a range of publishers.

In 1948, a US edition, with a 'Biographical Sketch of the Author by C. Hartley Grattan', exemplified 'the trans-national nature of book history in the twentieth century’ (Osborne, 'Temper Democratic; Bias Offensively Australian'). In 1991, annotated edition, with an introduction and notes by Frances Devlin-Glass, Robin Eaden, Lois Hoffmann and G. W. Turner was published by Oxford University Press. (A revised edition was published in 1999).

An electronic edition of Such Is Life is in preparation via the infrastructure offered by the Australian Electronic Scholarly Editing project. This edition will allow readers to ‘contribute to the edition with annotations and commentary’, providing ongoing opportunities for ‘critique, correction and debate’ (Osborne, 'Making the Archives Talk').

For further information on the publication history of Such Is Life, see the following:

- The Annotated Such is Life: Being Certain Extracts from the Diary of Tom Collins. (1991, rev. ed. 1999)

- (Ewers, John K. 'Such is Life Comes to the People.' Meanjin Papers 2.3 1943: 34-36

- Croft, Julian. 'Joseph Furphy.' Australian Literature, 1788-1914. (2001)

- Franklin, Miles, and Kate Baker. Joseph Furphy: The Legend of a Man and His Book. (1944, new ed. 2001)

- Osborne, Roger. '"Temper Democratic; Bias Offensively Australian" - Published in Chicago: The American Edition of Such Is Life.' Script and Print 34.4 (2010): 240-249

- Osborne, Roger. '"Making the Archives Talk": Towards an Electronic Edition of Joseph Furphy’s Such is Life.' JASAL 13.1 (2013): 1-19

-

Australian Digital Collections

The 1903 edition of Such Is Life is freely available through the University of Sydney's Australian Digital Collections, as are Rigby's Romance and Buln-Buln and the Brolga.

-

Many of the early newspaper and periodical reviews of Such Is Life have been digitised and are available online via the National Library of Australia's Trove service. See for example:

- 'Some Stories.' The Sydney Morning Herald 15 August 1903: 4

- 'Books, Publications, &c..' Australian Town and Country Journal 19 August 1903: 42

- 'An Australian Fielding.' The Register 22 August 1903: 8

and

- 'Literature.' The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser 26 August 1903: 518.

In addition to a generally favourable critical response in Australia, Such Is Life received notice in overseas journals. On 9 January 1904, for example, London's Athenaeum published a review of Furphy's novel alongside A. W. Jose's Two Awheel: And Some Others Afoot in Australia (1903). The Athenaeum review begins: 'The first of these volumes [Such Is Life] comes to us from the office of the most emphatically and aggressively Australian periodical in the whole great Commonwealth of the South [i.e. The Bulletin]… [Such Is Life] is essentially Australian in its every line as the wattle, the waratah, or the Sydney Bulletin. To the literary mind there is special interest attaching to fiction or other matter written in and of Australia. There are not many English-speaking lands left from which we may look for new developments in English literature. Australia is one of the few, and very interesting it is to watch her progress in letters' (43).

Reviews of Such Is Life continued in waves with each new edition or major re-publication. Critical responses to the novel began in the 1920s and were further boosted following the 1937 Jonathan Cape abridged edition. In 1943, Meanjin Papers recognised the centenary of Furphy's birth with a number of themed-contributions to its Spring issue. John Barnes's biography The Order of Things: A Life of Joseph Furphy appeared in 1990 and the Annotated Such Is Life was published the following year – both were published by Oxford University Press.

-

JASAL's Joseph Furphy Centenary Issue

In 2012, two conferences honoured the centenary of Furphy's death: 'a travelling conference through the Riverina in March, and a more formal seminar at Shepparton, the town where Furphy wrote his novel during the 1890s'. Most of the papers from both conferences appear in JASAL 13.1 (2013).

The papers include discussions on sexuality, mateship, Indigenous Australians, politics and anti-imperialism as they appear in Such Is Life. Other topics canvassed include the genesis, revision, publication history, vocabulary and structure of the novel.

-

Underneath the 'dislocation of anything resembling continuous narrative, run several undercurrents of plot, manifest to the reader, though ostensibly unnoticed by the author … In fact, the studied inconsecutiveness of the "memoirs" is made to mask coincidence and cross purposes' – Joseph Furphy, in an [Untitled commentary] commissioned by The Bulletin and published just prior to Such Is Life's release.

-

As A. K. Thomson remarks in 'The Greatness of Joseph Furphy', Such Is Life 'is really a hotch-potch of various ingenious ways in which a novel can be written’ (20). The following critical articles provide detailed examinations of the novel's structure.

- Susan K. Martin, in '"One Week in Each Opening": Furphy and the Use of the Diary Form' discusses 'the uses and implications of the diary form' in Such is Life and investigates how this form 'is both a way of holding the "novel" together, and a way of highlighting the fact that it was always falling apart'.

- Kerryn Goldsworthy, in her chapter 'Fiction from 1900 to 1970' in The Cambridge Companion to Australian Literature (2000) says that Such Is Life 'was at once a late experiment in realism and a very early anticipation of postmodern techniques of fragmentation, allusion, pastiche and authorial self-consciousness' (108). In its 'conception and execution', Such Is Life offers 'a conscious and deliberate rejection of one pre-Federation mode of writing: the masculine adventure version of nineteenth-century romance, as typified by the work of Henry Kingsley and Rolf Boldrewood' (108).

- Julian Croft, in 'Between Hay and Booligal: Tom Collins' Land and Joseph Furphy's Landscape' highlights the 'epic' nature of Furphy's novel. He notes that an epic 'articulates and celebrates the myths and common beliefs of a culture, and uses the tone of the core of that national audience'. Croft draws out the 'epic' elements of Furphy’s book – 'the courageous individual’s struggle against great odds', its task of making 'sense of the nation', and its depiction of 'the Gods at work in a mortal and fallen world' (158). In Croft's view, narrator Tom Collins 'presents the alert reader with the plot and mythic underpinning that all epics need' (158). By representing both 'the struggle for the land and its product' (158), Furphy is able to write 'two books at the same time': Collins’s diary of social life in the Riverina and his own 'national epic written in its many tongues' (159).

- John Barnes, in 'The Structure of Joseph Furphy's Such is Life', examines Furphy's method of 'federating stories'. Barnes considers that this approach enabled Furphy to discover 'an ingenious way of shaping his assortment of bush yams and bush memories into a significant whole' (388).

- In 'Reading the Three as One' Julian Croft outlines his experience of attempting a holistic reading of Such Is Life using the extant parts of the original text (including the excised portions that became the novels Rigby's Romance and The Buln-Buln and the Brolga. Croft concludes: 'Reading the three novels as one, and comparing the 1897 and 1903 versions, made me more convinced that in the re-writing Furphy lost control of the novel, and there are indications of contradictions and errors in the 1903 text which show that some of the lines of narrative surviving from 1897 slipped from his hands. But in losing control ... the 1903 Such is Life became a true novel of the twentieth century. By some amazing alchemical transition in the re-writing, Such is Life became a more Protean text and a touchstone of early modernism in the novel' (9).

-

Following her first visit to the home of Joseph Furphy’s parents, Kate Baker recalled that the kitchen walls were ‘inset with shelves filled with works of Shakespeare, Burns, Emerson, Mark Twain, Bret Harte, but books on theology predominated. A family Bible had a little niche to itself’ ('How I Met Joseph Furphy.' Meanjin Papers 2.3 (Spring 1943: 29). Such Is Life is 'studded with quotations' but, according to A. K. Thomson ('The Greatness of Joseph Furphy.' Meanjin Papers 2.3 (1943): 2-23), the novel is 'not bookish'. Thompson argues that Furphy's reading had become 'part of him' and 'his quotations are spontaneous' (22).

Robert Dixon, in '"A Nation for a Continent": Australian Literature and the Cartographic Imaginary of the Federation Era. Antipodes 28.1 (2014): 141-154, 254) suggests that Furphy 'builds the literary dimension of his work through a pattern of allusions to the texts he deems to be among the masterworks of world literature: Dante’s Inferno, Spenser’s Faerie Queene, Goethe’s Faust, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the King James Bible, and the works of Shakespeare' (149). But Dixon notes that Furphy's attitude to these texts is ambivalent. 'On the one hand, it reflects the structural anxiety of being a writer in a new world culture … On the other hand, it is often difficult to distinguish in Furphy’s literary allusions between homage and parody' (140).

John Barnes notes that Furphy's 'allusions to literature and to history go far beyond what was ever common property; and the point of many of the quotations and deliberate mis-quotations, the puns, the euphemisms, the careful synonyms, is lost on an increasing number of readers’ (298). Barnes accurately observes that ‘younger readers of … today' (he is writing in 1981) are unlikely to share Furphy’s knowledge of the Bible and of Shakespeare and even Furphy’s '"smal Latin and Less Greeke" are likely to be greater than those of most of his future readers in Australia' (Joseph Furphy. 1981:298).

To assist 21st century readers, Peter Hayes has compiled annotations to some of the literary allusions and quotations in Such Is Life as well as to the novel's 19th century colloquial language and its contemporary (but now historical) references. See Hayes's 'More "Ignorance-Shifting": Supplementary Annotations to the Second Annotated Edition of Joseph Furphy’s Such Is Life.' JASAL 14.3 (2014).

-

In his introduction to The Cambridge History of Australian Literature (2009) Peter Pierce writes:

'At a Sydney rally in support of the federation of its colonies into the Commonwealth of Australia in 1897 ... Edmund Barton ... grandly avowed that "For the first time in history, we have a nation for a continent, and a continent for a nation." Local poets had been hailing such a prospect for decades, in windy, idealistic verse. The 1890s had seen – largely by means of the Sydney weekly magazine, the The Bulletin – the rise to authority of some of the leading proto-nationalist, and still among the most enduring, figures in Australian literary history: Henry Lawson, A. B. 'Banjo' Paterson and Joseph Furphy principal among them. Such an emphasis on nation-making, particularly in the conflation of political and literary chronologies, would colour the writing of Australia’s literary history for generations' (1).

However, as Robert Dixon warns, in '"A Nation for a Continent": Australian Literature and the Cartographic Imaginary of the Federation Era', 'there is now a consensus in Australian scholarship that the sense of national identity apparently achieved in the literature of the Federation period is a retrospective creation of later decades, and especially of the 1950s ... In the works of both Henry Lawson and Joseph Furphy, "Australia" was not always "the unit," as Nettie Palmer had claimed in 1924 [ in Modern Australian Literature, 1900-1923 (1924):1], and their imagining of geosocial space ... is often threatened with uncertainty, ambiguity, and dissolution' (145, 146).

In her critical article '"Touches of Nature that Make the Whole World Kin": Furphy, Race and Anxiety' (Australian Literary Studies 19.4 (2000): 355-372), Frances Devlin-Glass concedes Pierce's argument that 'Furphy's novels were conceived at the height of nation-construction debates in Australia, and no doubt contributed to them, and were utilised for these purposes by literary nationalists from the 1940s'. But she argues that while Such is Life 'may constitute a clarion call to "One Australia", to stress this hegemonic aspect of the work is to overlook the relish Furphy clearly took in nationally and ethnically marked diversity and ethnology.'

For further analysis of nationalism and nation-making in Such Is Life, see also:

- Brady, Veronica. 'Such is Life, My Fellow Mummers': The Seditious Joseph Furphy.' Southerly 66.3 (2006): 27-36

- Goldsworthy, Kerryn. 'Fiction from 1900 to 1970.' The Cambridge Companion to Australian Literature Ed. Elizabeth Webby (2000): 105-133

and

- Carr,Richard Scott. ‘Writing the Nation, 1900-1940.’ A Companion to Australian Literature Since 1900 Ed. Nicholas Birns and Rebecca McNeer (2007): 157-172.

-

- For scholarly discussion on Furphy's portrayal of women, gender and sexuality, see Dawn Partington's 'Furphy and Women.' Southerly 29.2 (1999): 165-176. This article draws together much of the commentary from the 1980s and 1990s. See also Damien Barlow's 'Un/making Sexuality: Such Is Life and the Observant Queer Reader. ' Australian Literary Studies 21.2 (2003): 166-177.

- Several critics note connections between Furphy's writing and that of American writers Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson. See, for instance, Raymond Driehuis's 'Joseph Furphy and Some American Friends - Temper, Democratic; Bias, Offensively Self-Reliant.' Antipodes 14.2 (2000): 129-135.

- For the influence of Furphy's Christian and socialist principles on his writing, see Clive Hamer's 'The Christian Philosophy of Joseph Furphy.' Meanjin Quarterly 23.2 (1964): 142-153 and John Barnes's 'Joseph Furphy: The Philosopher at the Foundry.' JASAL 13.1 (2013): 1-17.

-

Child Lost on Goolumbulla

Child Lost on Goolumbulla is a short film adaptation of an episode from Chapter Five in Such Is Life.

http://www.youtube.com/embed/Is0KpQJhFRE -

In 1937, Mary Gilmore was one of three 'leading literary people' asked by the Melbourne journal All About Books to nominate 'twelve Australian Books that should be in every Australian home'. (The other two contributors were George Mackaness and Frederick T. Macartney.) Gilmore included Such Is Life in her list saying: 'Here is Australia in a period past; and here is a wide philosophy of life.' The full lists of the three guest contributors can be found in 'Twelve Australian Books That Should Be in Every Australian Home.' All about Books 9.11 (November 1937): 172).

-

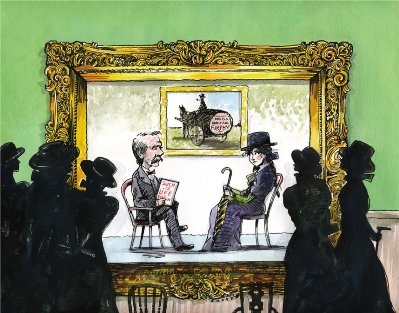

When Franklin Met Furphy

'In February 1904, Stella Miles Franklin – then aged 24 – received an admiring letter from a 60-year-old former bullock-driver named Joseph Furphy. He requested a photograph and proposed that they meet.' So begins Shane Maloney's account of Franklin and Furphy's Melbourne meeting (during which they were 'trailed by female fans' of Franklin).

Read Maloney's story on The Monthly's website.

-

A Furphy Water Tank

'Forged from Rural Life: A Furphy Water Tank'. Image sourced from the Sydney Morning Herald, 21 April 2012Joseph Furphy's brother, John, for whom Furphy worked while writing Such Is Life, was the inventor of a water cart – a 'cylindrical iron tank, mounted horizontally on a horse-drawn wooden frame with cast-iron wheels' with the family surname painted in large capitals on two sides.

The carts, 'generally known as furphies ... were used in large numbers by the Australian army in World War I. Drivers of the carts were noted for spreading gossip, and in time furphy became a synonym for idle rumour. The word was current in this sense by 1916 when C. J. Dennis used it in The Moods of Ginger Mick.' Coincidentally, Joseph Furphy's pen-name of 'Tom Collins' was in common use 'among bushmen at the end of the nineteenth century [and] carried the meaning that furphy now carries.' (Source: Barnes, John. 'Furphy, John (1842–1920).' Australian Dictionary of Biography (1972).)

For more about Furphy's time at his brother's foundry, see Barnes's 'Joseph Furphy: The Philosopher at the Foundry.' JASAL 13.1 (2013).

-

- There is additional information in AustLit about Joseph Furphy and Such Is Life – follow the links within Joseph Furphy's author record and the record for Such Is Life : Being Certain Extracts from the Diary of Tom Collins to explore more.

- Also visit the Joseph Furphy Digital Archive edited by Roger Osborne and published by AustLit.

- To further investigate topics such as critical articles dealing Australian national identity in the novels of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, go to the AustLit search page and explore the Advanced Search options. For help on building searches, visit the 'How to Search AustLit' page.

- For an understanding of the political events that led to Federation, many of which coincided with Furphy’s writing of Such Is Life, see the timeline provided by the Australian Parliamentary Education Office or the more extended chronology detailed by the National Archives of Australia.

- Some of Furphy's early contributions to the The Bulletin were published under the name 'Warrigal Jack' ('warrigal' being an Indigenous word for 'dingo' and 'jack' meaning 'knave'). To learn more about Australian colloquialisms, word origins and meanings, visit website of the Australian National Dictionary Centre.

- To discover more about Joseph Furphy's life, see the biographical accounts of his life. These include Edward Edgar Pescott's The Life Story of Joseph Furphy (1938), A. L. Archer's Tom Collins as I Knew Him (1941), Kate Baker and Miles Franklin's Joseph Furphy: The Legend of a Man and His Book (1944), Jean Lang's At the Toss of a Coin: Joseph Furphy: The WesternLink (1987) (focusing on Furphy's final years in Western Australia) and John Barnes's The Order of Things: A Life of Joseph Furphy (1990) (And see John Barnes's Bushman and Bookworm: Letters of Joseph Furphy, also published in 1990.) See also Furphy's entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography.

-

Tom Collins House, Perth

Furphy moved to Western Australian in 1905 to work with his sons in the family engineering and machinery business. In 1907, Furphy 'built a cottage in Servetus Street, Swanbourne, now relocated to the Allen Park Heritage Precinct. Known as Tom Collins House, it has been the headquarters of the Fellowship of Australian Writers, WA Branch since 1949'.

For more information on Tom Collins House, see the FAW WA Branch website.

You might be interested in...