AustLit

-

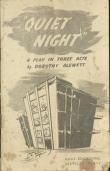

Quiet Night, written in ca. 1940, was a popular and successful play. Performed around Australia an in the UK the hospital drama obviously struck a chord with audiences of the 1940s and 1950s. It was also produced as a radio play in Australia and on the BBC in the UK. The version transcribed here was published in 1943 as a playscript recommended for production by the armed forces during World War II.

A scan of the original 1941 published version of the play, from which this transcript was derived, is available from the AustLit record. The French's Acting Edition of 1953 is yet to be transcribed.

-

Cover of the RAAF publicationSee full AustLit entry

Cover of the RAAF publicationSee full AustLit entry'Setting her action in a large hospital, Miss Blewett has undertaken no simple task in dealing with nursing from both its practical and psychological aspects, complicated in two cases by individual emotional strains. The play covers the hours of one hectic night in the hospital, in which the emotional preoccupations of several of the staff intrude on their professional duties' ('Australian Play' Argus 10 March 1941, 6).

Characters

SISTER MURPHY of the day staff at St.

(...more) -

QUIET NIGHT

by

DOROTHY BLEWETT

(1941)

PRODUCTION NOTES

The action of the play is fairly straightforward and should not present any great difficulty in production. The main interest lies in the fate of Nurse Sinclair; linked with this are the Sparrow-Macready romance (which precipitates the crisis in Nurse Sinclair's career), and Russell Keane, whose transfusion provides the way out for her. The sub-plot of the Dr. Clayton Sister Rankin-Mrs. Clayton triangle runs separately from the main plot but hos a parallel theme—sacrifice. The theme could be illustrated in Matron’s speech to Nurse Sinclair: "For the first time since you've been here you placed your patient’s welfare before your own interests. I am only sorry that your sacrifice was—futile..." Still, for Nurse Sinclair her sacrifice was a beginning, while, for Dr. Clayton and Sister Rankin, theirs meant the end of all they had been hoping for.

Mention to the actors the touch of dramatic irony in the scene between Russell Keane and Nurse Sinclair—"You did things together when you were kids, didn’t you—went for picnics, the, whole family, didn’t you?" Draw their attention to the scene later on when Nurse Sinclair tells Sister Rankin how unhappy she had been at home. She can hint at this by the way she says: "We did when we were little—when my own mother was alive. All families do, don’t they?"—But must be careful not to do anything to detract from the interest centering at that moment in Keane.

The most difficult part in the play will probably be the scene between Mrs. Clayton and her husband towards the end of Act II. Indeed the success of the ploy will depend on the casting of these two parts, especially the woman. The scene should be taken fairly quietly at first, with Leila trying to win her husband over by references to their early married life, while he is quite unmoved by it until she mentions Frances Rankin. There is a slight easing of the tension that is being worked up, when Dr. Clayton tries to get his wife to go back to bed. From Leila’s speech, "No, no—don't touch me…" until she falls sobbing at her husband's feet there must be a gradual increase in tempo and intensity. (See that it is gradual—don't let the actress expend all her thunder too soon.) Clayton turns to Frances, but she says "You must make up your own mind." Then slowly, half to himself, not really believing it, Clayton says " it’s all phantasy...There's none of it true"; but when his decision comes—"We could never forget this"—we know that the struggle is over.

There is a fair amount of telephoning throughout the play. A common fault is to take the lines too quickly without waiting to give the person at the other end time to say anything. It might help to suggest to the actors they should think up what the unexpressed half of the conversation might have been so that they can time their replies to give the impression they are really "hearing" the other person.

The set and the furniture should be limited to bare essentials.

If possible try to borrow genuine hospital furniture and uniforms—dresses, aprons, caps and stiff belts, collars and cuffs. Mrs. Clayton's dressing should be easy. Dr. Clayton will wear a lounge suit; Russell Keane, pyjamas and dressing gown; Macready, white doctor's coat in Acts 1 and 2, lounge suit in Act 3; Matron, white dress or long white coat.

For a reading keep your props to what can be managed with one hand. Remember the players have to cope with books. If you are not able to dress your cast the nurses might be suggested by caps; but the other characters should be able to get something approaching the costumes.

If you place the buzzing indicator in the fourth wall—that is, the audience—it will save a tricky and expensive prop and will enable the audience to see Patsy's reactions to the various summons.

Casting Suggestions:

Choose your lesser characters as foils to your more important ones; for instance, Williams should set Sparrow off.

Sinclair - about 29

Firm, brisk, efficient.

Sparrow - 20

Young, small, pretty, tendency to fluff.

Patsy - 18-20

Plenty of bounce not boisterous, just bubbling over with youthful spirits.

Mrs Clayton - 30-40

If possible should be frail, pretty, spoilt-looking, but looks in this part count less than acting ability.

Russel Keane - 19

Sophisticated—educated voice—well-mannered; guard against hysterical tone in his scene.

Dr. Clayton - 40-45

Tired, older than years, sensitive, should move quietly.

PEOPLE IN THE PLAY - In the order in which they speak

Sister Murphy

Probationer

Sister Rankin (Frances)

Nurse Ruth Sinclair—3rd Year

Nurse Jean Sparrow—1st Year

Nurse Williams—1st Year

Nurse Patsy Curtin—Junior

Nurse Smith

Nurse Roberts

Russel Keane

A Patient

Dr. Angus Macready

Resident Doctor at the Hospital

Mrs. Leila Clayton

A patient

The Matron

Dr. Richard Clayton

(Note.—The orderly, patient, etc., in the Second Act can be omitted without making necessary more than very minor alterations to the movement and dialogue.)

THE SCENE

The service section of the Memorial Ward of St. Agnes' Hospital. There is a desk on either side of the stage, each with its own greenshaded desk light and telephone. Doors left and right upstage lead to the entrance lobby and to the main corridor of the ward. A door downstage left leads to the kitchen. If possible the door of the kitchen should open so that cupboards and shining electrical equipment can be seen. The kitchen may be arranged at the centre back of the stage with its door next to another leading to the sterilising room. The doors should be labelled in neat letters. Centre back of the stage and above the door to the sterilising room is a dimly lighted indicator which shows the numbers of the various rooms when the indicator buzzes. Glass partitions, about 4' 6" should, if possible, screen the doors right and left. They should be low enough to let persons entering be seen properly, but high enough to give a suggestion of privacy to the two desks.

Inside the glass partition on one side are shelves on which the probationers put the vases of flowers.

Everything should be neat, workmanlike and shining. There is a cupboard downstage right for linen and a small wooden box for filing patients' history cards on the Sister's desk.

All the nurses must dress in strict nursing uniform. In the original production, all except the probationers wore white, with scarlet capes; the probationers wore lilac print dresses, white aprons and black shoes and stockings. Only the Sisters and the Matron wear flowing muslin caps; the others wear small nurses' caps.

The Time - The Present.

ACT I

When the curtain rises, Sister Murphy (Day Sister) is seated at the desk writing her report. She looks tired and her hair is untidy. As she writes, she pushes up wisps of her hair under her cap with her free hand. She finishes writing, blots the report and closes the book, then stretches herself wearily. Meanwhile, a probationer has entered left carrying a tray of used dishes. She crosses to kitchen and leaves tray, goes off left and returns with another similar tray. While she is on stage, Murphy straightens up and becomes business-like. As she is crossing to the kitchen the second time, Murphy speaks.

Murphy: Is that the last?

Probationer: Yes, Sister.

Murphy: Do the flowers as quickly as you can; the night staff will be here in a moment.

Probationer: Yes, Sister.

(Exit left. During the next speeches—until Patsy’s entrance—she goes on and off with vases of flowers which she stacks close together on shelf behind desk left.)

(Enter Sister Frances Rankin and Nurse Ruth Sinclair. They are fresh and brisk.)

Murphy: Don't be so offensively fresh. I'm tired as hell.

Rankin (picking up report book and reading it): Bad day?

Murphy: Foul. Which one of your nitwits put Mrs. Clayton's roses in Mrs. Spanner's room? It just about precipitated a major crisis to-day.

Sinclair: Little Patsy probably. She is practically not with us most of the time. Didn't you get them back for her?

Murphy (striking an appealing attitude): "I couldn't possibly have them now, Sister—not in my state of health. I know Mrs. Spanner's only got a broken arm—but in a hospital one never knows, does one?" God, that woman makes me sick. If she really had anything wrong with her, I wouldn't mind. Sorry, Rankin—I keep forgetting she's a friend of yours.

Rankin (stiffly): Not exactly a friend of mine—I worked with Dr. Clayton for a while, that's all.

Murphy: Ah ha! Not exactly a friend—

Sinclair (breaking in hurriedly): She may have nothing but imaginitis, but she pays, my dear, she pays. And she keeps another patient who can't pay.

Murphy (rises): Economics shouldn't be mixed up in a job like ours.

Rankin (recovering herself): Poor lamb, you are tired. I always know you're completely done when you get high-minded.

(Enter Nurse Jean Sparrow and Nurse Williams right.)

Rankin: Good evening, Nurse Sparrow. Good evening, Nurse Williams.

Sparrow & Williams: Good evening, Sister.

Rankin: Have a nice day off, Sparrow?

Sparrow: Lovely, thank you, Sister.

(Rankin hands Sparrow the report book. She and Williams take it to other desk and read reports. Rankin seats herself at desk where Murphy was sitting. She takes a small card index from drawer and starts to read entries on cards. Enter Patsy right, explosively.)

Rankin: You're late.

Patsy (almost in tears): I'm sorry, Sister. Someone's pinched my belt again.

Rankin: No belt, eh? Well, if Matron notices, don't expect me to protect you.

Patsy: No, Sister.

Rankin: What do you mean—"No, Sister"? (Gives her a playful smack on the rear.) Go and read the reports.

Patsy: Yes, Sister. (Shyly) You're a dear. (She goes over to desk and pushes Williams away from report book.)

Murphy: You all spoil that kid.

Sinclair: Much less trouble than slanging her, isn't it, Frances?

Rankin: She makes me laugh.

(Enter Nurses Smith and Roberts left. They are tired and crumpled. Smith carries a tray with clinical thermometer in jar of sterilising fluid and a small blackcovered notebook.)

Murphy: Haven't you two gone off yet?

Smith: Just finished, Sister. (She hands Rankin the black notebook.)

Murphy: Get along then.

Smith: Very well, Sister. (Takes tray into sterilising room.)

Murphy (reading notebook): Good night for you, Rankin. You'll all be able to get some sleep. Mrs. Nelson went home today and there's not a soul on the danger list.

Sinclair: Now if only dear Mrs. Clayton will behave herself—

Roberts: I'm afraid she isn't going to. She wants to see you before you go off, Sister. She says she feels one of her spasms coming on and she’s sure Dr. Moore would let her have a hypodermic.

Murphy: Is she indeed! What does she think the man is trying to do to her—turn her into a dope fiend? Will you have a look at her later on, Rankin?

Rankin: I'll see her when I go round.

Roberts (respectfully): She's rather anxious to see you, Sister Murphy.

She says Sister Rankin would poison her as soon as look at her.

Sinclair (interposing rapidly): You're quite right, Murphy; we shouldn't have to waste our time with people like her. It's nothing but pure hysteria. All she needs is half a dozen good hearty belts across the buttocks. (Roberts exits to kitchen.)

Rankin: Don't be coarse, Ruth. The young are listening.

Patsy: Oh, Sinclair, you're cruel. I think Mrs. Clayton's quite lovely—that gorgeous pale hair. And have you seen that green chiffon nightie; it's heavenly. (She sighs with envy.)

Sinclair: I know she's lovely to look at; but so's poison ivy. I can't make out how any man could stand her for twenty years, let alone a sensitive thing like Dr. Clayton.

Rankin: I can assure you she was quite irresistible twenty years ago. Patsy would have raved about her then—

Sinclair: I think you're just being charitable—

Rankin: Let's change the subject. Rounds, please, Patsy. You too, Nurse (to Sparrow). Nurse Williams, see if all the visitors have gone.

Williams: Yes, Sister.

(Williams goes into kitchen. Sparrow and Patsy go off left. Smith enters from sterilising room and goes into kitchen.)

Rankin: What's Smith doing here? I thought she was downstairs somewhere.

Murphy: Of course, you haven't heard the news. I forget you've been asleep all day while things are happening. My dear, little Burgess got the sack this morning—tipped out bag and baggage in about an hour.

Sinclair: What happened?

Murphy (shrugging): Matron just decided she "was not the right type for a nurse." Just that, nothing else.

Sinclair: She's a beast, that woman. It frightens me that I can hate anyone as I hate her.

Rankin: That's fear, my lass.

Sinclair: Oh yes, I admit it is. I've lived in fear every day for three years; I've wakened up in the night in a cold sweat because I'd dreamt I heard that sniveling little voice of hers—"I'm afraid you're not the right type for a nurse, Nurse Sinclair. Nursing is a noble profession—“. Only five more days of it, Francie—think of it. Five more days—and I'll be out of her power forever. I'm keeping my fingers crossed.

Murphy: I'll keep mine crossed for you, Sinclair. I'll admit none of us ever thought you'd stay the distance. Matron's sure had it in for you the whole time you've been here. She's done everything except sack you—

Sinclair: She wouldn't sack me—she likes power too much for that. She knows just exactly what getting through means to me; it's amused her to play cat-and-mouse with me for three years. In five days, it'll be beyond her power to hurt me—and I'm frightened—

(The indicator buzzes.)

Rankin: You'll have to snap out of that, my dear. (Raising her voice)

Nurse, Number 5.

(Enter Williams from kitchen.)

Williams: Yes, Sister. (She goes off left.)

Murphy: Heavens, look at the time.

(As she speaks Smith and Roberts enter from kitchen. They carry their capes and one carries some brightly coloured knitting. The other has a magazine under her arm. They are going off duty.)

Smith: Good-night, Sister.

Murphy: Good-night. You're off tomorrow, aren't you, Nurse Roberts?

Roberts: I certainly am.

Murphy: Well, have a good day.

Roberts: I'll do my best. Good-night. (She and Smith exit right.)

(Enter Patsy and Probationer. They have their heads together and are giggling over something. Murphy has been gathering up her cape, etc.)

Murphy (to Probationer): Good heavens, child; I thought I’d sent you off half an hour ago. Go on, get along with you.

Probationer: I'm just going. Good-night, Sister.

(She goes off right.)

Murphy: "And so saying, she swept out."

(She gives a mock salute and goes off right.)

Sinclair (picking up temperature book): I suppose I may as well do these first as last. (Sits at desk.)

Rankin: I'll do rounds—avoiding Leila Clayton, if possible.

Sinclair: She'll be asleep by now.

(Enter Williams from ward.)

Williams: Patsy, Mrs. Spanner wants a pan.

Patsy: She can't, not already.

Rankin (speaking as she goes off left): She probably knows her own mind best on that, Patsy.

Patsy: All I can say is, she's no camel, that woman.

(She goes into sterilising room, re-entering almost immediately with a bed pan covered with a blue cotton cloth. She goes off left.)

Williams: Shall I do Miss Maughton's foment, Nurse?

Sinclair: Yes, Nurse. Where is Sparrow?

Williams: She’s settling Mrs. Watson for the night. Her visitors just went.

Sinclair: When she's done that, she'd better go down and get the milk. I'm ready for my cocoa.

(She begins entering temperatures on charts.)

Williams: I'll tell her.

Sinclair (sharply): Alright, get on with it.

(Williams, offended, goes back into kitchen. She reenters in a few seconds, carrying a small bowl of steaming water. She crosses stage, carefully avoiding looking at Sinclair.)

Sinclair: Sorry, Bill. I'm all of a twit these days.

Williams: You certainly are pretty edgy.

Sinclair: So will you be when you've only got five days to go.

(Enter Russell Keane in pyjamas and slippers, left. His right arm is bound closely to his body; his dressing-gown is properly on his left shoulder and he clutches it round him with his left hand.)

Williams: When I've only five days to go, I'll be a little ray of sunshine.

Russell: You're a little ray of sunshine already.

Sinclair: Here, what are you doing out of bed. You'll have to go back, you know.

Russell (coming downstage and seating himself on edge of other desk):

Don't be so damn nursey. I don't want to go to bed.

Sinclair: You'll have to—

Russell: You'll have to carry me, the n.

Williams: I'll leave it to you, Sinclair. (She goes off left.)

Sinclair: You're an awful nuisance, you know. There'd be the devil to pay if Matie found you here.

Russell: What a down you've all got on Matron! She's quite a decent old scout—been nice and motherly to me.

Sinclair: She would be. You're personable and male.

Russell: We are nice and catty to-night, aren't we? So you've noticed my charm too, have you?

Sinclair: I've noticed that you're completely spoiled. Now, please go back to bed. We will carry you, you know, if you won't walk—

Russell: Don't send me back there, by myself, with no one to talk to and nothing to do but listen to that awful woman in the next room. She's done nothing but whine all day. What’s wrong with her?

Sinclair: Mostly nerves.

Russell: I'll be as bad as she is soon, if I have to listen to much more of her.

Sinclair: I'll move your bed to the other side of the room; you won't hear her then.

Russell: No, no, don't do that.

Sinclair: Do you know what you do want.

Russell: Yes, I want company.

Sinclair: You sound like a very little boy. Is 'ums afraid of the dark then? Is that what made you come out here—or just sheer cussedness?

Russell: I'm unhappy—and I'm sick.

Sinclair: You don't give yourself a chance, you know. You'll get better much quicker if you stick to the rules—

Russell: It isn't just this. (He touches his injured arm and his dressing gown falls back.) It's everything.

Sinclair: Even if everything is out of tune, you may as well be comfortable. (She comes across and pulls his dressing gown round him, buttons it and ties the cord.) There, is that better? How did you get this? (Touches his injured arm.)

Russell: Car turned over. (Proudly) I should have been killed by rights—I was doing ninety.

Sinclair: I don't think that's anything to brag about. It sounds stupid to me. What were you doing it for?

Russell: Experience. You see, I'm trying everything—

Sinclair: How old are you?

Russell: I'm twenty next month. Dad is giving me a Gipsy Moth for my birthday.

Sinclair: And by the time you're twenty-one, there'll be nothing left for you to try.

Russell: Oh, yes, there will. I'm going to sheep-farm later on; but I've got to sow a few oats first. I've got it all mapped out. When I'm twenty-two, I'm going to have a mistress—install her in a flat. You know—champagne out of shoes, mink coats and diamond bracelets and all the trimmings.

Sinclair: A bit old-fashioned, but nice work—if you can afford it.

Russell: Oh, I can afford it alright. If Mother won't finance me, Dad will. That's one thing there's always plenty of—money.

Sinclair: Are there things there aren't plenty of?

Russell (moodily, after a minute's silence): What's the first thing you can remember?

Sinclair: A cup and saucer my gran gave me. It had violets and maidenhair fern painted inside the cup. I'll never forget it; I still think it's the prettiest cup I've ever seen.

Russell: You see—that's the kind of first memory most people have. The first thing I remember is my father fondling my nurse and my mother catching them at it.

Sinclair: You poor kid! What did your mother do about it?

Russel: Nothing. She forgave him gracefully—and has gone on forgiving him ever since. It suited her very nicely.

Sinclair: Aren’t you being rather hard?

Russell: You've got brothers and sisters, haven't you?

Sinclair: Brothers—lots of them.

Russell: You did things together when you were kids didn't you— went for picnics, the whole family, didn't you?

Sinclair·: We did when we were little—when my own mother was alive. All families do, don't they?

Russell: The Keanes don't. I can never remember going out with both my father and mother—not once.

Sinclair: I'd be sorry for you if you weren't so sorry for yourself.

Russell: I don't go in for self-pity as a rule—there isn't time. But you get too much time when you're in bed, doing nothing all day.

Sinclair: No visitors to-day?

Russell: Mother came. She brought one of her platonic boy friends. And he brought a bottle of whisky. So good for a fractured clavicle and two broken ribs. (With sudden passion) Can you wonder I'm rotten right through—with a mother like that?

Sinclair: Look, you really must go back to bed—this isn't doing you a bit of good.

Russell: Oh, for God's sake let me get it off my chest. I've never had time to think about it before—there's always been some way of running away from thoughts. But there isn't here—there's nothing to do but think, and think, and go on thinking.

Sinclair: If you want my private opinion, you can't be so bad, or you wouldn’t have thoughts to run away from. Your parents have been good to you, haven't they? You'd have been worse off if there'd been a divorce.

Russell: I don't know that I would. There's something cleaner about an absolute cut. Anyway, I don't believe either of them want a divorce. Technically, I suppose Mother is quite guiltless—she goes in for mental infidelity, if you know what I mean. The old man's more natural—but I've got an idea he finds the fact that he's married makes things less complicated for him. Nobody can expect anything from a man whose wife won't divorce him. He plays it up for all it's worth, and it's worth plenty, women being what they are.

Sinclair: I don't know whether you're a cynical young beast or something that ought to make me weep tears of blood—

(Enter Sparrow, right. She carries a tray with large Jug and two or three covered plates.)

Sparrow: Heavens, is he still out?

Sinclair: He's been telling me the story of his life, and I can't make up my mind whether to feel sorry for him or to go and have a nice clean drink of cool water.

Russell (bitterly): Thanks. Perhaps I'd better go back to bed—

Sparrow: Come along and I'll tuck you in.

(Sparrow takes Russell by his uninjured arm and they turn to go off left. As they go out, Sinclair speaks.)

Sinclair: I'll bring you a drink in a few minutes, Russell—and I'll ask Sister if you can have something to chase those thoughts off for the night.

Russell: Thank you, Nurse. You don't really think I'm a beast, do you?

Sinclair: Of course not, you young rabbit. There's some way out, you know.

Russell: Perhaps. I'll let you know if I find it. I'll be glad to get back to bed—I feel a little sick—

Sparrow: My goodness, come along then.

(Exit Sparrow and Russell, left.)

(Sinclair picks up the tray and takes it into the kitchen. Returns to stage and reseats herself at desk and goes on with charts. Enter Patsy with bed pan covered with cloth. She takes it into sterilising room. As she does so, the indicator buzzes. Patsy re-enters, looks up at indicator, then goes off left. Enter Rankin, right; she seats herself at other desk.)

Rankin: They're having a fine time downstairs in nine. A visitor gave some cream cakes to an appendicectomy.

Sinclair: Visitors ought to be searched.

Rankin: I suppose it's too much to expect them to use just ordinary common sense.

(Enter Patsy left.)

Patsy: Nurse Sparrow would like you to come and see Mr. Keane, please. Sister. She doesn't like the look of him.

Rankin: Neither do I, for that matter. Rather a nasty Iittle boy, I thought—

Sinclair: So did I, until I talked to him to-night. I think he might be quite a decent lad if only he got the chance.

Patsy (respectfully): If you would please hurry Sister. I think he's spitting blood—

Rankin (horrified): What! (She hurries competently out, left.)

Patsy: Would that be hemorrhage, Nurse?

Sinclair: It would, my child. He must have bumped his broken rib into his lung, the stupid young fool. How about some cocoa, Patsy; I need it.

Patsy: Yes, Nurse. (She goes into kitchen. Enter Williams left with tray and bowl she carried out. The bowl is no longer steaming.)

Sinclair: Is everyone settled for the night, Nurse?

Williams (pausing at door of sterilising room): Only Mr. Patterson still to do. He was reading—and feeling ill-used—

Sinclair: I'm sorry for Mrs. Patterson.

Williams: I saw her last night. I think maybe he doesn't get much chance at home, so he's taking it out on us.

Sinclair: It's a way they have.

(Williams goes into sterilising room. The indicator buzzes.)

Sinclair (raising her voice slightly): Number 9 is ringing, Patsy.

Patsy (entering from kitchen): He wants a drink of water and the window open if it's shut and shut if it's open. Watch the cocoa, please, Nurse.

(Enter Sparrow left, and goes straight across to telephone, speaking as she crosses the stage.)

Sparrow: Ice, please, Nurse—lots of it, as quickly as you can.

Patsy: Yes, Nurse. (Goes out right. Comes back and puts head round corner) Look after Number 9, Williams. The cocoa will have to take its chance. (Goes off right.)

Sparrow (at phone): Dr. Macready, please…Sister Rank in would be glad if you would come straight away to Number 6. Special...Mr. Keane; hemorrhage…Dr. Clayton's case; shall I ring him?...Very well, Doctor. (Puts down phone.)

Sparrow: I wish Patsy would hurry with the ice.

Sinclair: She won't be long. Never mind Nine, Nurse—watch the cocoa.

Williams: Yes, Nurse Sinclair. (She goes into kitchen.)

Sparrow: Will he die, Sinclair?

Sinclair: Not necessarily—if the bleeding can be stopped before he loses too much.

Sparrow (miserably): I'll never be a good nurse. I can't just be competent and do the right things. My feelings get tangled up with the patients themselves—as people, I mean, not as patients.

(Enter Williams with steaming jug and cups and saucers on tray which she sets on Sinclair's desk.)

Sinclair: You'll grow out of that. If you're worth your salt, you get interested in the things that are wrong with them. It's almost as though their illnesses are something apart from the people themselves—

Williams: We haven't all got your brains.

(She pours out cups of cocoa.)

Sinclair (ignoring the interruption): That's why Mrs. Clayton fascinates me so. I think as a woman she's thoroughly despicable; but I've always wanted to nurse a case of pure hysteria…

(Enter Patsy right with bowl covered carefully with white cloth.)

Sparrow: Oh, thank goodness. Did you have to wait till it froze, Patsy?

(Takes bowl and goes off left.)

Patsy: That's gratitude for you. Did you give Nine his drink, Nurse?

Williams: Good lord, I forgot him. Fix him, Patsy, while I pour your cocoa.

Patsy (going off left): What a life! I wish I'd stuck to something quiet, like charing. (Exit.)

Williams: Do you mean to say Mrs. Clayton just imagines those spasms of pain? If she does, the stage has lost a real actress.

Sinclair: Oh, no—she feels them alright, but the cause of them is mental, not physical. She's using them as a barrier to protect herself from something she doesn't want to face—something she'll have to face as soon as she's better.

Williams: Sounds weak to me. I suppose it's all this divorce business she's funking. She told me last night she was letting Dr. Clayton divorce her because if she divorced him, it might injure his practice, and she didn't want to do that. I didn't say anything, but she must think we're dumb if she thinks she can get away with that. Everyone knows she's been round the world with that Harrington man.

(Enter Patsy left.)

Patsy: He only wanted the window closed and a touch of womanly pillow-thumping. A bachelor, too—I don't think it's seemly.

Williams: Don't interrupt, infant. What she can see in a beefy red—faced man like Harrington, I can't imagine. Perhaps as a contrast to Dr. Clayton—he's the gentlest thing I've ever seen.

Sinclair: He's probably spoiled her hopelessly ever since they've been married. All this business about her allowing him to divorce her to save his practice is just the kind of thing a spoiled woman would say—and there's dozens who'll believe it too. Most people are fools.

(Enter Sparrow left.)

Sparrow: Sister sent me to get my supper. You’re to relieve me if you've finished, Bill.

Williams: Just about; I'll snatch another cup-a when I get a chance.

(She takes a last gulp of cocoa· then goes off left.)

(Sparrow sits down wearily at desk. Patsy pours a cup of cocoa and hands it to her.)

Sinclair: Does it seem worse because he's so good-looking and so young?

Sparrow: Please don't be sarcastic, Sinclair—I can't bear it. It just seems such unutterable waste.

Sinclair: You'll learn detachment—it's the only way.

Sparrow: I don't think I ever will. I was born soft.

(Enter Dr. Macready right. He wears a white linen double breasted tunic and a stethoscope sticks out of his pocket.)

Macready (looking over the partition at Sparrow): Hullo there, young Jeanie.

Sparrow (primly): Good evening, Dr. Macready.

Macready: Whist there, wuman. Smile when ye speak to me .

Sparrow: I see nothing to smile at, Dr. Macready.

Macready: And what's more, I have a bone to pick with ye.

Sparrow: I suppose you'd still pick bones if Matron were sitting round the corner—

Macready: I had the presence of mind to notice that yon wuman is on the ground floor being impressive to Sir Edwin Aitken, no less. And so she ought to be—she's just lost his best patient for him—

Sparrow: And meantime, your patient is bleeding to death—

Macready: You're a bad-tempered wench—but I still like ye.

(He goes off left.)

Patsy: And amid all the sickness, pain and one thing and another, lurve blossomed like a red, red rose.

Sparrow (dimpling): I'll screw your neck, young Patsy.

Patsy: Oh, I'll say, "Bless you, my children" with tears in my voice.

I'm not jealous—I never did like Scotchmen.

Sparrow (involuntarily): Scots.

(Patsy picks up used cups and goes into kitchen.)

Sinclair: Watch your step, Twitter. You know what would happen if you were caught together outside the hospital. It'd mean the sack for you, without the option. Matron could do Macready a lot of harm too. Theoretically, she can't, but you know what she is—

Sparrow: Don't worry. I've never been out with him yet—he wanted me to last night—gosh, I was tempted. It's—rotten, you know—

Sinclair: He won't stay here long—he's really brilliant—although he is such a young fool.

Sparrow: He isn't really.

(The buzzer rings.)

Sinclair: Mrs. Clayton. I suppose she's heard the disturbance in Keane's room and wants to know what's doing. I'll go; Patsy, you'd better wash up.

(Enter Williams left.)

Williams: Sister wants you to phone Dr. Clayton, Nurse Sinclair.

Sinclair: Alright—

Williams: She said to ask him to come right away. I think Scotch Angus is worried.

Sinclair (picking up phone): I don't wonder; it's rather a shock. (Into phone) Get Dr. Clayton. Urgent…Yes, I'll hang on.

Williams: Sister got out of him that he fell when he got out of bed.

Sinclair: If only the silly young idiot had told me instead of sitting here talking—

Williams: I don't see how you can be blamed.

(Enter left Mrs. Clayton, very quietly. She is dressed in a rather exotic dressing gown beneath which shows the hem of a chiffon nightdress. Her feet are thrust into high-heeled mules decorated with feathers. None of the nurses notice her and she stands just at the corner of the partition listening.)

Sinclair (at phone): Dr. Clayton please. St. Agnes' Hospital here...Is there any way of getting on to him? The matter is very urgent. Please do so, if it's possible…Mr. Russell Keane; hemorrhage…Yes, thank you. (Puts down phone. Exit Williams.) He's out; he would be. (Turns and sees Mrs. Clayton.) Is anything the matter, Mrs. Clayton?

Mrs. Clayton: I've been waiting and waiting for Sister Murphy; I sent for her and she didn't come. I must have something to make me sleep—I can't do without sleep. It's most unprofessional of Sister Murphy. Of course, I wouldn't expect anything at all of Sister Rankin; she has always disliked me. I had to keep her in her place, of course, when she was my husband's attendant. But Sister Murphy—I did expect consideration from her—I sent for her—

Sinclair: Sister Murphy went off duty an hour or more ago, Mrs. Clayton; you've been asleep since then.

Mrs. Clayton: Asleep! How can you say such a thing, Nurse—I haven't closed my eyes for forty-eight hours.

Sinclair: I assure you you were sound asleep when I looked in as I was coming on duty, Mrs. Clayton. Come along now, back to bed, there's a dear. (She goes over and endeavours to slip her arm under Mrs. Clayton's.)

Mrs. Clayton: Please don't touch me, Nurse. You are a most unsympathetic person—

(Enter Patsy from kitchen; she goes over to collect Sparrow's cup.)

Sinclair: Yes, I know, and you can't bear to be touched by anyone unsympathetic—but you'll have to put up with it to-night, because all the sympathetic members of the staff are looking after a very bad case.

Mrs. Clayton: You hate me, don't you? Everybody here hates me—I can feel it like a mist around me. It blots out everything else; it confuses me. I shall complain to Matron in the morning and demand to be moved—

Sparrow (moving over to her): Come along with me—I don't hate you.

Patsy here thinks you're beautiful, don't you, Patsy?

Mrs. Clayton: Do you really? Of course, when I'm dressed—

Patsy: Oh, I think your things are lovely, Mrs. Clayton—that chiffon nightdress—

Mrs. Clayton (with pathetic satisfaction): It is sweet, isn't it?

Patsy (sighing with envy): Heavenly—just like a trousseau.

Mrs. Clayton (violently): No, no, no, it isn't. Not a bit like a trousseau

Sparrow (hurriedly pouring oil on troubled waters): Would you like a nice fresh cup of tea when you get into bed—and perhaps Sister will let you have something to help you to sleep—

Mrs. Clayton: Frances Rankin! Don't let her give me anything; she's hoping to poison me, you know-

Sinclair: I'll pour it out myself. You needn't be afraid. Go on back to bed now. You must give yourself a chance, you know, or it will take you longer to get well.

Mrs. Clayton: Do you think I'm any better?

Sinclair (with the air of one watching an insect on a pin): No. I think you're worse.

Mrs. Clayton (with satisfaction, allowing herself to be led away): I feel worse; I feel much worse.

Sparrow (as she walks towards exit left with Mrs. Clayton): You are very bad, you know, coming out here. If Matron caught you there'd be a terrible row—

Mrs. Clayton: That horrid young man in the next room to mine walks about—I hear him going in and out—

Sparrow: He's made himself really sick to-night, anyhow.

Mrs. Clayton (stopping to talk about it): That's why you were phoning my husband, wasn’t it? I heard you.

Sinclair: Mrs. Clayton, you really must go back to bed—

Mrs. Clayton: My husband is coming here to-night, isn't he? Isn't he?

Sinclair: He may not think it necessary.

Mrs. Clayton: He'll think it necessary—he thinks of nothing but his patients. What time is he coming?

Sparrow: Mrs. Clayton, you must come to bed now, at once. If you don't be nice to us, you can't expect us to be nice to you, now can you? (Mrs. Clayton allows herself to be led off left by Sparrow.)

Sinclair: That woman's pathological. She should be in a bughouse, not here.

Patsy: I feel sorry for her. She's not really mad, is she?

Sinclair: She's on the way, I should say. Imagining someone is trying to poison them is one of the signs.

Patsy: How do you know these things, Nurse? Will I have to learn about them?

Sinclair: Oh, I've always been interested in mental cases. The old doctor up home used to lend me books and talk to me about cases. (She is talking more to herself than to Patsy.) I understand them better now when I think about them than I did then.

Patsy (enviously): You're so clever, Nurse Sinclair.

Sinclair: I'm keen. I've thought about nothing but being a nurse since I was about twelve—You'll have to make Sister some fresh cocoa, Patsy—

Patsy: Yes, Nurse.

(Enter Sparrow left.)

Sinclair: Did you get her off?

Sparrow: She's terribly excited about something. I wish we could give her something to calm her down.

Sinclair: She could have some aspirin. Here you are. (Opens drawer of desk and takes out bottle of white mixture.) Make out it's something very strong and it'll settle her down.

Sparrow: She's just about a borderline case, isn't she?

Sinclair: Patsy here feels sorry for her.

Sparrow: So do I a bit—I suppose because she's so pretty—

Sinclair: Don't waste your sympathy. I'd bet ten pounds if I had it to a penny she's responsible herself for everything that's happened to her. Divorce looked nice and romantic and she's always had everything she wanted; but now she's in it, it doesn't look so good and she's trying to bury her head in the sand.

Sparrow: She's gone beyond the stage of being responsible now, I should think—

Sinclair: Probably always been unstable emotionally. And now someone else will have to be responsible for her—it isn't fair, somehow. Patsy, you'd better take the ten o'clock temperatures, instead of standing there looking impressed. I'm going to relieve Sister.

Patsy: Very well, Nurse Sinclair.

(Sinclair goes off left.)

Patsy: That's a soda—there's only about half a dozen of them. You'll have to do the two o'clocks now, Twitter.

(As they talk, Patsy goes into sterilising room and comes out with tray, with thermometer in jar and small night lamp. She lights the lamp, picks up small black notebook from Sinclair's desk, finds pencil and places them on tray. Sparrow goes into kitchen, returns with tray and medicine glass. Measures mixture into glass. Makes entry in book. Puts bottle of mixture on tray.)

Sparrow: I do feel sorry for Mrs. Clayton, in spite of all Sinclair says.

Patsy: Sinclair's marvelous—she gives you the feeling that she's so sure always—

Sparrow: She is, too. I wish sometimes I could be as detached about cases as she is—but I'm not made that way, so there it is.

Patsy: Just as well she is keen—she'll still be a nurse when you and Angus are crooning to your grandchildren.

Sparrow: You're a cheeky young devil. Sinclair's quite attractive really—or she would be if she'd only let herself be soft now and again. She's so determined to get through brilliantly—

Patsy: I wonder why she's so keen.

Sparrow: I believe she's pretty hard up—ran away from home to do her training, or something like that. She never seems to get any letters or have any friends outside the hospital. It’s a queer, lonely kind of existence. I don't know what I'd do without interests outside the hospital—

Patsy: It seems to me your hands are pretty full with interest inside the hospital.

Sparrow: I haven't seen Dr. Macready go down, have you? He must still be in with Russell.

Patsy: Association of ideas they call it, don't they? (Sarcastically) He might have gone down without saying anything to anyone as he went past.

Sparrow (seriously): I don't think he'd do that.

Patsy: What I like about love, it sharpens the sense of humour so.

Sparrow: You're quite ridiculous, Patsy. There's simply no question of—anything like that. He just amuses me.

(Enter Angus left.)

Patsy: Enter the angels, tripping lightly.

Angus: Good evening, Nurse Patsy. Is it me then you're likening to an angel?

Patsy: Good evening, Doctor. (Demurely) It was Nurse Sparrow that more or less dragged your name into the conversation. (The buzzer rings) Mrs. Spanner—the usual, I presume.

(Goes off left.)

Angus: Tactful girl, young Patsy.

Sparrow: That's a quality you should admire.

Angus: Now you're just being provocative in the hope that you'll deflect me from my purpose.

Sparrow: I'm sure nothing could do that.

Angus: You're right there. I've made up my mind to pick a bone with ye and pick it I will. What do you mean by backing out like you did last night—after I'd bought the tickets and all?

Sparrow: It must have bitten into your Scotch soul to waste them.

Angus: Waste them, waste them! Losh, wuman, I didna waste them.

You're not the only lassie in Melbourne, ye ken.

Sparrow: You're lucky to be able to pick and choose, Dr. Macready.

Angus: I believe you're jealous. Jeanie, you're sweet when you're jealous.

Sparrow: Jealous! Me jealous! You flatter yourself, Dr. Macready.

Angus: And you've got a bit of fire in you too. I like a woman to have a bit of fire in her.

Sparrow: An experienced man like you should know.

Angus: Ye know, they've got a word for girls like you in Scotland.

Sparrow: They've got words for lots of things in Scotland. Superlative place—I wonder you didn't stay there.

Angus: Have I ever told you why I came out here?

Sparrow: It must be the only thing you haven't told me.

Angus: I haven't told you that I love you, have I?

Sparrow: Not since last Tuesday—about this time. Why don't you keep to the subject—"Why I left Scotland"—doubt less for Scotland's good.

Angus: It all started when I was but a little lad. My mother used to have lodgers—what you'd call "roomers," do ye ken?

Sparrow: Now you've gone all American. Try "boarders," then maybe I'll get your meaning.

Angus: Boarders, is it? Well, one of my mother's boarders was a young man from this very town of Melbourne. Up at the University he was studying medicine. And I remember how in my childish thirst for knowledge, I asked him why he'd come to Edinburgh to study medicine and he said, if you'll believe it, that Melbourne was too hard for him. Twice they'd canned him here in Melbourne, so here he was in Edinburgh to get through there, because it was easier. That very day, I said to my mother, "Mother, when I grow large enough"—I was only a little laddie in those days, with curls, if you'll believe it—"Mother," I said, "I'm going to Melbourne to study medicine. It's harder there." And Mother said, "That's a noble ambition, my son, and a noble profession." And I said, "Yes, Mother, for I'd like fine to have a handle to my name and have all the nurses saying, respectfully mind you, 'Yes, Dr. Macready' and 'Certainly, Dr. Macready.'"

Sparrow: What a pity most of them say, "No, Dr. Macready." Still, it's a pretty story—if true.

Angus: And romantic. Romance, that's what appeals. Everything I do has a touch of romance—even to falling in love with a pigheaded wench who won't even let me touch her hand—

Sparrow (melting): Darling Angus.

Angus: May I touch your hands, Jeanie? (He holds out both his hands. She crosses to meet him and he takes her hands and kisses the palms, first one, then the other—very slowly.) They taste of carbolic.

Sparrow (laughing): How very disappointing.

Angus: If you ever smell of disinfectant when we're married, I'll divorce you.

Sparrow (gasping): When we're married—

Angus: Well, what else did you think all this was leading up to?

Sparrow: But you hardly know me—

Angus: I know that I love you, love you most truly, Jeanie. Losh, wuman, you're not going to be coy, are you?

Sparrow: No, Angus.

Angus (meaning it): Thank goodness. (He starts to draw her into his arms.)

Sparrow (evading him): Angus—we must be careful. If Matron saw us—

Angus: What could she do?

Sparrow: She could give me the sack—she'd be glad of an excuse, I'm sure—I 'II never be a good nurse—

Angus: Well, it wouldn't matter then.

Sparrow: My people are making sacrifices to let me do this, Angus. I can't let them down as easily as that. Matron could do you a lot of harm, too—she's pretty powerful, you know—

Angus: We'll think of some way of seeing each other—the old besom couldn't growl if you went to tea with my mother, could she?

Sparrow: Do you think your mother would want me?

Angus: She's sick of the sound of your name already.

(Enter Sinclair left. She crosses kitchen, speaking as she goes.)

Sinclair: Don't mind me. I'm deaf and practically blind. (Goes into kitchen.)

Sparrow: Let me go, Angus—someone else might come.

Angus: Not till you've promised to go to tea with my mother on your next day off—

Sparrow: That's next Wednesday. Angus, I'll be so shy.

Angus: You mustn’t be, my sweet. Jeanie, it is true, isn't it?

Sparrow (breathlessly): Yes-oh, yes, Angus. .

(He kisses her, taking a long time about it. Enter Matron and Dr. Clayton right.)

Matron: (speaking as they come on): It was fortunate the message reached you so promptly.

(Sparrow gives a startled gasp, breaks away from Angus and runs across to kitchen.)

Clayton: Another two seconds and I'd have been away. Ah, there you are, Dr. Macready.

Angus (recovering his sang froid with scarcely an effort): Good evening Dr. Clayton. I'm glad you were able to get here so soon.

Matron (putting a lot of meaning into her words): We caught him in the nick of time, Dr. Macready.

Angus: That was very lucky, Matron. (As they speak, they go off left. The stage is empty for a moment, then Sparrow enters from the kitchen, drops into chair behind desk left. Speaks to Sinclair who is still in kitchen.)

Sparrow: Oh, goodness, what on earth will I do? I'm sure she saw us—I don't see how she could help it.

Sinclair (entering from kitchen): For heaven's sake, pull yourself together; act as though nothing's happened and just sit tight.

Sparrow: I can't Nurse, really I can't. If she speaks to me for the next three days, I’ll just burst into tears. I'm a fool, I know—

Sinclair: Well, keep out of her way. (Sees medicine) What's this?

Sparrow: Good heavens—I forgot Mrs. Clayton.

Sinclair: Take it along at once-—and if you do run into Matron, for heaven's sake don't look self-conscious.

Sparrow: Alright, I'll try—but I know I'll do something stupid—I know me so well. Sinclair, she couldn't really do Angus any harm, could she?

Sinclair: She could—if she wanted to. But I don't think she would, not spitefully. She does what she thinks is her duty. Here, buzz off before she comes back—

(Sparrow takes tray and goes off left. Sinclair makes entry in report book. The telephone on desk rings.)

Sinclair (at telephone): Yes— Yes, Matron is here. Just hang on for a moment and I'll get her. (Puts down phone and exits left, returning almost immediately, followed by Matron. Matron picks up phone.)

Matron: Yes…Yes, do that please. I'll be down in a few minutes. (She replaces phone slowly and precisely.) Nurse Sinclair, when I came into this wing a few minutes ago, I was astounded to see one of the nurses here with Dr. Macready. It was not you, was it?

Sinclair: No, Matron, it was not I.

Matron: I think you know who it was. (Sinclair is silent.) Don't you?

Sinclair: Yes, Matron.

Matron (impatiently): Well? I am waiting, Nurse.

Sinclair: You surely don't expect me to tell you—

Matron: I do expect you to tell me. You know the rules of this hospital as well as I do, Nurse Sinclair.

Sinclair (half to herself, as though she is not sure it is really happening): I suppose one excuse is as good as another. I am not going to tell you—

Matron: Nurse Sinclair, the whole time you have been in this hospital, you have been most impatient of discipline. I have overlooked breaches of the hospital rules on several occasions, but this time. I refuse to have my authority flouted. You will see me in my study in the morning as you go off duty. I have grave doubts of your suitability for nursing—

Sinclair: And less than five minutes ago, I said you weren't spiteful.

Matron: Don't try me too far, Nurse.

Sinclair: You can't do this to me—

Matron: You are getting hysterical, Nurse. (She turns abruptly and goes out right. Sinclair stands in the same tense attitude without moving until the curtain falls. Enter Patsy with temperature tray. The buzzer rings and Patsy looks up at indicator.)

Patsy (as one who has learnt a lesson): Mrs. Spanner wants a pan. (She goes into sterilising room, returning with covered pan. As she does so, the buzzer rings again and both telephones ring.)

Patsy: The telephone, Nurse. (Sinclair takes no notice. Patsy comes to centre stage with pan under arm and picks up one phone; the other phone rings again. She tries to take it up and drops the pan. Enter Sparrow left.)

Sparrow: Patsy, Number 9 wants a pan—

Patsy (endeavoring to answer both phones at once): No, Matron isn't here. She went downstairs ten minutes ago. (Puts one phone down.) Hullo... Hullo... Special Ward here (she drops the pan.) Patsy! They should have called me "Pansy."

QUICK CURTAIN.

ACT II

Scene: The same

When the curtain rises, Rankin is seated at desk left writing up reports. The reading lamp on desk is only light, although light shines through from main entrance, right. The kitchen door opens-the kitchen is lighted and Sinclair enters, closing the door behind her. She seats herself wearily at the other desk and leans her head on her hands. There is a moment or so of silence before Rankin speaks.

Rankin: Can't you sleep?

Sinclair: Sleep! Don't be stupid. I'm sorry, Frances. (Rankin goes on writing. After a second or two of silence, a clock strikes two. Very softly.) Have you ever wished you had the guts to kill someone?

Rankin (startled into telling the truth): Yes, oh yes. I could have too—quite easily—

Sinclair: She said to-night you were hoping to poison her—

Rankin: Who said that?

Sinclair: Leila Clayton—that's whom you meant, isn't it?

Rankin: I didn't know—anyone knew—

Sinclair: I don't suppose anyone else does, except Dr. Clayton himself. You glow when he's in a room—

Rankin (stiffy): I didn't know I was so transparent—

Sinclair: Don't mind my talking, Frances—if I don't I'll probably do something desperate. After all, we've lived pretty close together all these years. You helped me when I first came here—I was so green. Pity it's all going to be wasted.

Rankin: Aren't you rather jumping to conclusions? You may have misunderstood Matron. You were anticipating something—I'm wondering if you didn't go more than halfway to meet it.

Sinclair: I wish I could persuade myself I did misunderstand her. I've thought and thought ...but it was just an excuse. She knows perfectly well it was Sparrow. Nothing in this hospital ever gets past her. She knew before she asked that I wouldn't say. (With rising passion) Frances, she can't do this to me—she can't...There must be some way of stopping her; she shouldn't have so much power...

Rankin: Ruth, you mustn't let yourself be stampeded. Take it for granted you're only going to get a dressing-down in the morning. You've had them before—they're no novelty. Don't go into Matron's study with your mind already mode up—it's inviting trouble. I'll talk to Sparrow; she'll have to go to Matron herself and confess.

Sinclair: You musn't do that, Frances. This is my business

Rankin: Do I have to remind you that wing at night is my business.

Sinclair (bitterly): I'm afraid I think of you as my friend, not as Night Sister in charge of the Memorial Wing.

Rankin: I didn't mean it that way Ruth, and you know I didn't. But you must realise that it is my business and my responsibility.

Sinclair: Yes, I know-I know. I think Matron was right. I am a bit hysterical. But when your whole life falls about your ears, you're surely allowed to be—just a little bit hysterical—

Rankin: Your whole life, Ruth? You're exaggerating—you're young, you've got any amount of ability; there are a dozen things you can do—

Sinclair: When I leave here to-morrow—yes, it will be to-morrow, it's no good saying it won't—when I leave here, I'll have exactly £11 in the world, and you know how long a woman con live on that.

Rankin (a bit embarrassed at talking about money): I didn't know that…What about your people?

Sinclair: As far as they're concerned, I don't exist.

(A buzzer rings. The kitchen door opens and Sparrow comes out, yawning and huddled under her cape.)

Rankin: It's Mr. Mortimer, Nurse. You'd better do the two o'clock temperatures too. Don't let Mr. Mortimer talk—he makes him self too excited.

Sparrow (stifling another yawn): Yes, Sister.

Rankin: Didn't you have any sleep to-day?

Sparrow: I've had my night off—I never can settle down after it.

Rankin: Mr. Mortimer may have some A.P.C. if his throat is troublesome.

Sparrow: Yes, Sister. (She goes out left, still yawning and shivering with her arms folded under her cape.)

Rankin: Have you told her (indicating the retreating Sparrow) about the rumpus?

Sinclair: No.

Rankin: Why not?

Sinclair: I tell you she's only an excuse—

Rankin: I still think you're wrong. Matron probably honestly wanted to know who it was—you know how down she is on any goings-on between the meds. and the staff. Sparrow's a nice kid, but she'll never finish her training. She's the sort that marries—if not Macready, then someone else. It's unthinkable for you to ruin yourself for her—

Sinclair: Sparrow doesn't come into it. It's a personal matter— between Matron and me. She was wonderful to me when I first started here—I'd have done anything for her, and she knew it. That was when she changed—as soon as she knew how much power she had over me, she started to use it. I hate her now; she's a sadist, Frances—you've said it yourself—

Rankin: I know I have—but I don't think I ever really meant it. At the back of my mind, I've always known her reason for the things she's done that looked—well, deliberately cruel.

Sinclair: Like sacking young Burgess this morning, with an hour's notice!

Rankin: I happen to know why Burgess was sacked. Matron told me herself this evening. It was something to do with one of the furnace men—oh, quite disgusting. That's not for publication, Ruth. Matron would rather be slanged herself than brand the girl forever.

Sinclair: Young Burgess!

Rankin: Probably there have been reasons just as good for the other things she's done.

Sinclair: I didn't know you admired her so much

Rankin: I'm trying to make you reasonable—that's all.

(Enter Sparrow left.)

Sparrow: Mr. Mortimer's throat seems very sore, Sister. I told him he could have some A. P.C.

Rankin: Has he had some already this evening?

Sparrow: Yes, Sister. Five grains.

Rankin: Give him another five then, Nurse. And perhaps he'll see that his children have their tonsils out at a reasonable age.

Sparrow: I didn't know he was married even. Gosh, and here have I been wasting my ammunition on an old married man!

Rankin: I didn't say he was married. I'm interested in his tonsils, not his eligibility.

Sparrow (going into kitchen as she speaks): Fancy saying a word like that at two o'clock in the morning. (She comes back almost immediately with a bottle of white mixture and a medicine glass on a small tray. She comes across to Rankin, who reads the inscription on the medicine bottle and nods. Rankin replaces bottle on tray.)

Rankin: You'd better get the junior to help you with the temperatures.

Sparrow: Patsy! She's sound asleep still. She snores.

Rankin: Does she? I believe she's got adenoids. I'll ward her one of these days and get one of the specialists to run over her. She gets far too many colds.

Sinclair: You fuss over that child like a mother.

Rankin: She's a nice kid, Ruth—and she makes me laugh.

(Exit Sparrow left.)

Sinclair: I believe you'd forgive anyone anything who made you laugh.

Rankin: Well, life isn't so amusing that we can afford to miss any laughs.

Sinclair: Poor Frances—and here am I shelving my worries on to you too.

Rankin: There's no need to pity me. I think that perhaps-very soon—I shall be very happy. We haven't dared to make plans—

Sinclair: Well, it looks as though the sooner the lovely Leila gets better and out of here, the sooner the divorce can go through.

Rankin: I suppose I'm a fool, but I can't reconcile myself to building our happiness on a broken marriage. I might have happened much sooner if I could have. Anyway, Leila asked for the divorce herself.

Sinclair: I said to-night that we'd been pretty close together all these years—but I don't believe I know you very well, after all.

Rankin: I was just thinking the same when Sparrow came in. And now I do want to know things. Why did you say that as far as your people were concerned, you don't exist?

Sinclair: I swept out—just like the heroine of a melodrama. Only not into the snow. My mother died when I was only eight—I used to try and wait on her when she was ill. I think it was that that made me want to be a nurse—I knew she needn't have died if she'd had proper attention—

Rankin: I didn't even know your mother was dead; you never talk about yourself—

Sinclair: I've tried, subconsciously most of the time, to shut all that went before behind a wall of silence. It kept it further away when I didn't talk about it. My father married again within a few months—I suppose you can’t blame him—I have three brothers all younger than I am, and in the shortest possible time thereafter, I had three half-brothers. You can perhaps imagine what my life was like from the moment I was old enough to lift a kettle on to the stove. I don't think my father meant to be cruel—he just can't conceive Iife that isn't made up of a ceaseless round of work...If you'd ever lived on a poor farm, you'd know what I mean—

Rankin: You're an amazing person, Ruth; all these years, and you've never shown the slightest sign of all this—

Sinclair: I'm adaptable—it didn't take me long to absorb the atmosphere you others are used to. Some of the time it's been like walking on eggshells—

Rankin: But why?

Sinclair: I couldn't be myself-at least, I think I've been more myself here. That other Ruth Sinclair who walked five miles to school and milked eight cows morning and afternoon, who fed and mended for six brothers—that was the sham. I was always obsessed with the idea of being a nurse. The moment I was eighteen, I wrote to Matron—I don't know what made me choose St. Agnes'—it might just as well have been one of the provincial hospitals. But I'd seen a photo of St. Agnes'; it satisfied something in me. Matron wrote back—you know the usual letter. I showed it to my father—he just laughed and threw it into the fire. After that, I never mentioned it again at home; I just saved like mad. It took me nine years to save the £50 I needed to come down to town; and all the time I was terrified I wouldn't be able to get enough before I turned thirty. I'm talking too much, Frances—why don't you stop me? I'll be ashamed in the morning that I said all this—

Francis: Why should you be? You've got people all wrongly, Ruth your background doesn't matter—it's you yourself that counts. I'm saying it badly—

Sinclair: It may seem like that to you, Frances. Your background is so safe, so sure—it may seem just background to you—to me, it's the whole picture—

Rankin: I wish I could somehow make you see how unimportant it is.

Sinclair: I wish I could make you understand what those outback farms are like. You might understand my point of view then. I've been in your home; I know how much has been spent on making life easier and more pleasant. On the farm, we just didn't spend a penny except on the grimmest necessities. It wasn't conscious saving, not miserliness—just sheer, stark lack of money—that, and a total ignorance that any other kind of life is possible.

Rankin: Ruth, where did you learn to speak the way you do? That's not the kind of thing you can absorb as you can atmosphere—

Sinclair: There's an old doctor up home—a dipsomaniac, if the truth must be told. It's queer the things that shape one's life, Frances—we had two cases of diphtheria at the school when I was about twelve and he came to take swabs of our throats. I helped him—I was the oldest girl at the school—our neighbourhood went in for boys in a big way. He got interested in me and after that, he used to lend me books to read—I read the Lancet and Rutledge on Forensic Medicine before I read Anne of Green Gables.

Rankin: This is like slabs of a romantic novel, you know—

Sinclair: It wasn't romantic—romance in Gunnersen's Crossing was limited to being taken down behind the cowshed by one of the boys on Sunday afternoon after church. Why the cowshed, Frances? I've often wondered.

Rankin: l suppose it had some kind of esoteric symbolism—

Sinclair: You're telling me!

Rankin: Ruth, will you· promise me something? Promise me you won't be defiant. Give her a chance to back down gracefully—I think she'll take it. Please, Ruth—

Sinclair: And give her another chance to crow over me—

Rankin: After all you've put up with, are you going to throw it all away—everything you've worked and slaved for all these years. Can't you eat humble pie—just once? It’d only be for five days—

Sinclair: Supposing she asks me again about Sparrow; would you tell if you were me? Of course, you wouldn’t; you know darn well you wouldn't—

Rankin (slowly): I think I would—if I were you.

Sinclair: What do you mean by that?

Rankin: Your career's so much more important than any schoolgirl ideas about not sneaking. After all, Sparrow and Macready are so obvious, Matron's sure to see for herself—if she hasn’t done so already.

Sinclair: She knows alright—that's what makes it worse. She's using it as an excuse.

Rankin: Stop that, Ruth, it's no good going over and over that. She won't sack you out of hand, she couldn’t over a thing like that. She has a committee she has to report to—no, she’ll give you another chance—and you take it. Tell her anything she asks—do anything she says—but get through these five days somehow—

Sinclair: I suppose I must—

Rankin: Of course you must. I'll speak to Matron if I get a chance—it won't do any harm and it may give her an excuse for backing down.

Sinclair: Thanks, Francie—I wish I thought it worthwhile. I'd better wake the adenoidal junior, I suppose, and show her how to do a foment. (She stands up and stretches herself) God, I'm tired! You must be too—and I've kept you here airing my family history. (She touches Rankin's shoulder affectionately as she passes her. She goes into kitchen and closes the door behind her.)

(Rankin makes entry in report book and closes it. She takes out a magazine which she props up against the base of the desk light and produces some knitting. She goes on with the knitting, reading at the same time. Enter Sparrow with tray, with bottle of mixture and medicine glass empty.)

Rankin: Good heavens, I forgot you were still with Mr. Mortimer. Has he settled down?

Sparrow: I've heard the story of his life for the fourth night in succession—

Rankin: You'll have to learn to be firm with the patients; you can't have them talking all night—it does them no good, you know, no matter how sleepless they feel—

Sparrow: I know, Sister. I really did try to get away—but he's so terribly persistent. I think his throat was paining too.

Rankin: All right. You'd better get on with the temperatures at once.

Sparrow: I peeped in to see that Williams was getting on alright with Russell. He wasn't asleep—

Rankin: Neither was she, I hope—

Sparrow: No, she wasn't. (She goes into kitchen and leaves tray, she comes back on to stage; as she does so, the telephone rings)

Rankin (at phone): Yes, Sister…Yes. How long will they be? Alright, we'll be ready by then…Number 7, that's right. (She puts down phone) There's a pneumonia case coming in in about half an hour, Nurse. Leave the temperatures. Nurse Curtin will have to do them. Prepare number seven.

Sparrow: Yes, Sister. (She goes off left. Enter Sinclair from kitchen.)

Sinclair: Did I hear you say prepare number seven?

Rankin: Pneumonia; coming in in about half an hour. Patsy will have to do the two o'clocks; Williams can't leave young Keane. You might have a look in as you go past, Ruth—

Sinclair: I believe they borrowed our kettle in number three about a week ago; did we get it back?

Rankin: I don't remember. (Enter Patsy with tray and bowl of steaming water with small folded towel on tray.) When you've done that foment, Nurse, go down to Three and see if they still have our pneumonia kettle—

Patsy: Are we getting a pneumonia? That's one thing about Special, we do see life.

Rankin: You talk too much for your age; juniors should be seen only occasionally and heard still less.

Patsy (respectfully): Yes, Sister. (She goes off left, speaking as she goes) All the same, I think you like variety too.

Sinclair: She's incorrigible.

Rankin: Absolutely uninhibited—lucky child. It's pleasant though, isn't it, to strike a youngster so natural and fearless—

Sinclair: Much pleasanter than a mass of complexes like me, you mean.

Rankin: Oh, for heaven's sake, Ruth—don't be self-centred all the time.

Sinclair: Am I self-centred? I suppose I am—it's always been me against the world—

Rankin: Only in your own mind. You face the world with a sword in your hand—and the world answers back with swords. Good lord I'm talking in metaphors; it’s the effect you have on me, Ruth. (Enter Williams left.) What is it, Nurse?

Williams: His breathing is very shallow, Sister.

Rankin: Pulse?

Williams: Very quick, and it seems to me to be getting weaker.

Rankin: I'll be there in a moment, Nurse.

Williams: Yes, Sister. (She goes off left.)

Rankin: Saline injection.

Sinclair: Seems indicated. I'll get it.

Rankin: I'll fix it; you do the temperatures, Ruth. I wonder if Sparrow has finished number seven—

Sinclair: (going into sterilising room as she speaks) Patsy's right—we do get variety.

(Rankin goes into kitchen and can be seen through the open door arranging dishes on a tray. Sinclair returns to stage with tray, thermometer in jar of fluid, night lamp. She picks up black notebook from desk and places a pencil on tray, then consults report book. Enter Dr. Clayton right.)

Clayton: Good-night, Nurse.

Sinclair (starting): Goodness! Oh, good-night, Doctor.

Clayton: I'm sorry I startled you.

Sinclair: I was a million miles away.

Clayton: As far as that! I was passing on my way home; thought I’d have a look at young Keane. How is he?

Sinclair: Sister Rankin is just preparing a saline injection.

Clayton: H'm. I'll have a look at him.

Sinclair: Sister's in the kitchen—

(Enter Rankin from kitchen. Her tray has on it several small enamel lishes.)

Rankin: I was just going to ring you, Doctor.

Clayton: Lucky I called in—I was getting, back from a case. (Sinclair picks up tray and goes off left.) You’re tired, Frances—

Rankin: Not as tired as you look, my dear. (He kisses her.)

Clayton: I hate this hole and corner business of snatching moments with you, Frances. Thank goodness it will soon be over—

Rankin (sharply): Don't let us plan ahead, Richard—

Clayton: Still feeling it isn't right, Francie—

Rankin: It might be unlucky. Now you'll laugh at me—I'm not generally superstitious. But luck seems to hang to lucky people—and Leila’s been lucky all her life.

Clayton: Lucky to marry an unsatisfactory man like me?

Rankin: You know you wouldn't be unsatisfactory with anyone else.

Clayton: I won’t be to you, Frances?

Rankin: You do need a lot of reassuring, Richard. I thought it was generally women who needed all the reassurance—

Clayton: Don't believe it. Women are always ten times surer of themselves and what they want than men are.

Rankin: Another illusion gone!

Clayton: Do you stiII have iIIusions, Frances?

Rankin: I still think people can live happily ever after, Richard.

Clayton: Can they, Frances? I wonder. Fairy tale come true.

Rankin: Why not, oh, why not? We've earned it, Richard.

Clayton: It doesn't always follow, my dear.

Rankin: We can make it follow.

Clayton: You've altered, Frances; you've made up your mind at last—

Rankin: l've been watching Leila since she's been in here—I've realized what I’ve been condemning you to all these years. I should have had the nerve to face the business squarely—although there was still your practice to think of.

Clayton: Never mind; it's behind us now. We can forget it.

Rankin: Are we being middle-aged fools, Richard?

Clayton: I don't feel middle-aged when I'm with you, Frances.

Rankin: You are a darling…You've forgotten your patients for five whole minutes, Richard.

Clayton: And I've made you forget yours—that's an achievement. I'II have a look at him before you give him that injection. Are you coming along, Sister Rankin?

Rankin: Certainly, Doctor.

Clayton: You're like a small girl playing at nurses when you talk like that—

Rankin: We are middle-aged fools, Richard-I'm quite sure of that—

(Enter Patsy with tray, bowl, etc., which she carried out.)

Clayton: Good evening, Nurse.

Patsy: Good evening, Doctor Clayton. Is it still evening? I was hoping it was getting along towards morning.

Clayton: Tired?

Patsy: Not really: We all talk like that, but it's a pose of course.

Rankin: Don't forget the kettle, Nurse.

Patsy: No, Sister…I'll go down for it now—

(While they are speaking, Clayton goes off left followed by Rankin. Patsy goes into kitchen and leaves tray, etc. Sparrow enters left, goes into sterilising room and comes out again immediately with folded sheets. Enter Patsy from kitchen.)

Sparrow: Where's everybody?

Patsy: Sinclair's doing the temps, I think. Williams's still with Russell and Sister went along there with Dr. Clayton. Twitter, I think I know something.

Sparrow: Not really! Darling, you amaze me.

Patsy: Don't be sarky—it doesn’t fit your sweet jeune-fille type. You know, when I came in a few minutes ago, I'd have sworn Rankin and Dr. Clayton were gazing into each other's eyes, view above—you know—

Sparrow: Old stuff, my sweet. She thinks it's a grim dark secret, but practically everybody in the State knows, I should think.

Patsy: The things that happen in this hospital that I know nothing about! You'd think Rankin would put in a word for Sinclair with Matron, wouldn't you?

Sparrow: What for?

Patsy (uncomfortably realising that Sparrow knows nothing): Oh, just on general principles—

Sparrow: Look here, young Patsy, what did you mean?

Patsy: I thought you knew all about it—there was a bit of a rumpus to-night; Matie arrived here at the wrong moment—

(As she speaks, Sinclair enters left with tray, thermometer, etc.)

Sinclair: Shut up, Patsy.

Sparrow: It's too late, Sinclair; she's not to shut up. Matron did catch Angus and me? What's she going to do—and what is it to do with you? She didn't think it was you, did she?

Sinclair: She knows darn well it wasn't. She's just using the whole incident as an excuse to sack me, probably.

Sparrow: But she can't do that!

Sinclair: She won't ask your permission, my dear. Now don't get all upset, Sparrow—it's nothing to do with you. Patsy, have you got that kettle yet?

Patsy: Not yet, Nurse. I was—

Sinclair: Well, get along and get it. And keep your mouth shut for the rest of the night. You've done enough harm already.

Patsy: I'm terribly sorry—

Sinclair: Get out, will you? (Exit Patsy right.)

Sparrow: This is terrible—I had no idea—why didn't somebody tell me?

Sinclair: Will you stop getting excited about it? As far as you are concerned the incident is closed…Although it might be as well for you and Macready to be a bit more discreet if you both want to stay in this hospital—

Sparrow: Does Angus know? What will he think of me, letting someone else in for all this?

Sinclair: If he has any sense, he'll lie low—

Sparrow: I'll go in and see Matron as I go off duty—

Sinclair: Once and for all, Sparrow, keep out of this. Go and finish that room; the patient will be here any moment—

Sparrow: Yes, Nurse. (She turns to go off left.)

Sinclair: Don't worry, Sparrow. Rankin thinks Matie will only slang me—and I'm used to that.

Sparrow: You're putting me in rather a rotten position, but I suppose it's my own fault—

Sinclair: I think Matie's just showing off; you know how she loves picking on me—it must be biting into her soul that she’s only got a few more days of that sport. Now stop it once and for all. Is number seven ready?

Sparrow: Yes, at once.

(Sparrow goes into sterilising room; comes out almost immediately with stone or aluminium water bottles. Sinclair makes entries in report book.)

Sinclair: Hurry, Nurse. I think I hear the lift coming up now. Come straight back.

(Enter Williams left. She crosses to phone.)

Sparrow: Yes, Nurse. (She goes off left returning without bottles just as patient arrives.)

Williams: (at phone): Records? Send up Mr. Russell Keane’s card immediately, please…Alright, I’ll come down and get it; but keep calm for Gawd’s sake. (She puts down phone) She hates being wakened, lazy hound.

Sinclair: Transfusion?

Williams: Looks like. Poor kid—it’s all such stupid waste.

Sinclair: He’s not dead yet. You’d better go and get that card.

Williams: I’m going. Gee, here’s your case. (Door right is held open and tray wheeled in. The patient is bolstered up with pillows. An orderly wheels the tray; a nurse walks beside it, also a woman in outdoor clothes. Williams goes off right.)

Sinclair: Alright, Nurse. (She takes her place beside tray and other nurse exits right.) Oxygen, Nurse (to Sparrow).

Sparrow: Yes, Nurse. (She goes off right. Orderly wheels tray off left. Sinclair accompanying and followed by woman. Enter Patsy right with pneumonia kettle. Goes into sterilising room. Enter Sparrow right carrying cylinder of oxygen. Patsy comes out of sterilising room.)

Patsy: Oxygen, eh? Is the case in?

Sparrow: yes. Is that the kettle? You’ve taken long enough getting it.

Patsy: Had to search the whole damn hospital. Found it down in Path. Now what would they be wanting it for in the looney-bin?

Sparrow: Lots of loonies get pneumonia. They die of that mostly—not from being nit-witted. Here, give me that. (She takes kettle from Patsy and goes off left.)

Patsy: Well, that saves me wigging. (She goes over and reads the report book. The buzzer rings. Patsy looks up at it.) Mrs. Spanner! Not a pan, surely, Mrs. Spanner. So very unusual, Mrs. Spanner. (She goes towards sterilising room and phone rings. Comes back and answers phone.) Hullo…No, I’m sorry Nurse Sparrow is not here at the moment. Could I take any message for her, Doctor? (The orderly walks through wheeling empty tray.)...Ni, just as you please, Doctor. (She laughs.) Shall I tell her exactly that?...Very well, Doctor. (Puts down phone and goes into sterilising room; comes out with covered bedpan. Enter Williams right, carrying large blue record card.)

Patsy: Hullo, what’s records for?

Williams: You’re an inquisitive child.

Patsy: Yes, I know. It’s always been one of my strong points. Still, I do get to know things—

Williams: It’s Russell Keane’s. And much good will it do you.

Patsy: What do they want it for?

Williams: I politely refrained from questioning Dr. Clayton—although I suppose you wouldn’t have. But I gathered they desire to study his card in order to find out into which category his blood falls, so that, when making the necessary transfusion, they will not give him the wrong type blood.

Patsy: A transfusion! Gosh, that’s exciting—I’ve never seen one done. (Comes over and looks at card.) Where does it say?

Williams: There—see. “O” type.

Patsy: That’s the type there’s hardly any of, isn’t it?