AustLit

Latest Issues

Includes

-

1y

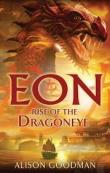

The Two Pearls of Wisdom

Dragoneye Reborn

Pymble

:

HarperCollins Australia

,

2008

Z1495619

2008

single work

novel

young adult

fantasy

'Eon is a potential Dragoneye, able to manipulate wind and water to nurture and protect the land. But Eon also has a dark secret. He is really Eona, found by a power-hungry master of the Dragon Magic in a search for the new Dragoneye. Because females are forbidden to practise the art, Eona endures years of study concealed as a boy. Eona becomes Eon, and a dangerous gamble is put into play. Eon's unprecedented display of skill at the Dragoneye ceremony places him in the centre of a power struggle between the Emperor and his High Lord brother. The Emperor immediately summons Eon to court to protect his son and heir. Quickly learning to navigate the treacherous court politics, Eon makes some unexpected alliances, and a deadly enemy in a Dragoneye turned traitor.' (Publisher's blurb.)

The Two Pearls of Wisdom

Dragoneye Reborn

Pymble

:

HarperCollins Australia

,

2008

Z1495619

2008

single work

novel

young adult

fantasy

'Eon is a potential Dragoneye, able to manipulate wind and water to nurture and protect the land. But Eon also has a dark secret. He is really Eona, found by a power-hungry master of the Dragon Magic in a search for the new Dragoneye. Because females are forbidden to practise the art, Eona endures years of study concealed as a boy. Eona becomes Eon, and a dangerous gamble is put into play. Eon's unprecedented display of skill at the Dragoneye ceremony places him in the centre of a power struggle between the Emperor and his High Lord brother. The Emperor immediately summons Eon to court to protect his son and heir. Quickly learning to navigate the treacherous court politics, Eon makes some unexpected alliances, and a deadly enemy in a Dragoneye turned traitor.' (Publisher's blurb.)

-

2y

Eona

Eona : The Last Dragoneye

Pymble

:

HarperCollins Australia

,

2011

Z1770501

2011

single work

novel

young adult

fantasy

'Once she was Eon, a girl disguised as a boy, risking her life for the chance to become a Dragoneye apprentice. Now she is Eona, thrust into the role of her country′s saviour.

Eona

Eona : The Last Dragoneye

Pymble

:

HarperCollins Australia

,

2011

Z1770501

2011

single work

novel

young adult

fantasy

'Once she was Eon, a girl disguised as a boy, risking her life for the chance to become a Dragoneye apprentice. Now she is Eona, thrust into the role of her country′s saviour.

'But Eona has an even more dangerous secret - she cannot control her power. When she tries to bond with her Mirror Dragon, the anguish of the ten spirit beasts whose Dragoneyes were murdered surges through her. The result: a killing force that destroys everything before it.

'On the run from High Lord Sethon′s army, Eona and her friends must help the Pearl Emperor, Kygo, wrest back his throne. Everyone is relying on Eona′s power. Can she face her own darkness within, and drive a desperate bargain with an old enemy? A wrong move could obliterate them all.

'Against a thrilling backdrop of explosive combat, ruthless power struggles and exotic lore, Eona is the gripping story of a remarkable warrior who must find the strength to walk a deadly line between truth and justice.' (From the publisher's website.)

Publication Details of Only Known VersionEarliest 2 Known Versions of

Works about this Work

-

From Middle Earth to Westeros : Medievalism, Proliferation and Paratextuality

2016

single work

criticism

— Appears in: New Directions in Popular Fiction : Genre, Distribution, Reproduction 2016; (p. 201-221)'This chapter argues that setting is a privileged aspect of the popular fantasy genre, and it analyses setting in terms of both how texts are created and how they are circulated and enjoyed. ‘Plot driven’ and ‘character driven’ are commonplace descriptions of modern fiction, and often mark a distinction between genres of differing value. While these phrases are most usually deployed in non-academic writing such as reviews and other opinion-based works, they have appeared in recent research around reading and empathy. According to Frank Lachmann, readers of so-called literary works scored higher in empathy tests than readers of popular fiction; he suggests that this is because empathy is more readily aroused by ‘character-driven’ fiction where ‘the emotional repertoire of the reader is enlarged’ than by ‘plot-driven’ fiction (2015, p. 144). I note that Lachmann makes no attempt to elaborate on what these phrases might specifically mean, nor is there any consideration of the ‘emotional repertoire’ of, say, romance fiction, which fits his definition of character driven and yet remains the most reviled of the popular genres. While, to my mind, good fiction needs to attend to both plot and character equally well, neither of these necessary aspects of storytelling comes readily to mind as a ‘driver’ when thinking about fantasy fiction. In fact, the big engine of the genre appears to be the exposition and elaboration of the setting, from which characterisation and plots specific to the setting are then generated. Fantasy novels are, in many ways, setting driven, a feature that marks them out as unique among popular genres. Other genres where setting is an acknowledged pleasure are historical fiction (for example the work of Philippa Gregory or Diana Gabaldon) and the exotic travel memoir (for example texts set in aspirational destinations such as Provence and Tuscany); but these at least rely on settings that are real. Fantasy fiction, on the other hand, invites readers to immerse themselves in and admire an incredibly detailed world that is an invention of the author’s imagination.' (Introduction)

-

From Middle Earth to Westeros : Medievalism, Proliferation and Paratextuality

2016

single work

criticism

— Appears in: New Directions in Popular Fiction : Genre, Distribution, Reproduction 2016; (p. 201-221)'This chapter argues that setting is a privileged aspect of the popular fantasy genre, and it analyses setting in terms of both how texts are created and how they are circulated and enjoyed. ‘Plot driven’ and ‘character driven’ are commonplace descriptions of modern fiction, and often mark a distinction between genres of differing value. While these phrases are most usually deployed in non-academic writing such as reviews and other opinion-based works, they have appeared in recent research around reading and empathy. According to Frank Lachmann, readers of so-called literary works scored higher in empathy tests than readers of popular fiction; he suggests that this is because empathy is more readily aroused by ‘character-driven’ fiction where ‘the emotional repertoire of the reader is enlarged’ than by ‘plot-driven’ fiction (2015, p. 144). I note that Lachmann makes no attempt to elaborate on what these phrases might specifically mean, nor is there any consideration of the ‘emotional repertoire’ of, say, romance fiction, which fits his definition of character driven and yet remains the most reviled of the popular genres. While, to my mind, good fiction needs to attend to both plot and character equally well, neither of these necessary aspects of storytelling comes readily to mind as a ‘driver’ when thinking about fantasy fiction. In fact, the big engine of the genre appears to be the exposition and elaboration of the setting, from which characterisation and plots specific to the setting are then generated. Fantasy novels are, in many ways, setting driven, a feature that marks them out as unique among popular genres. Other genres where setting is an acknowledged pleasure are historical fiction (for example the work of Philippa Gregory or Diana Gabaldon) and the exotic travel memoir (for example texts set in aspirational destinations such as Provence and Tuscany); but these at least rely on settings that are real. Fantasy fiction, on the other hand, invites readers to immerse themselves in and admire an incredibly detailed world that is an invention of the author’s imagination.' (Introduction)