AustLit

-

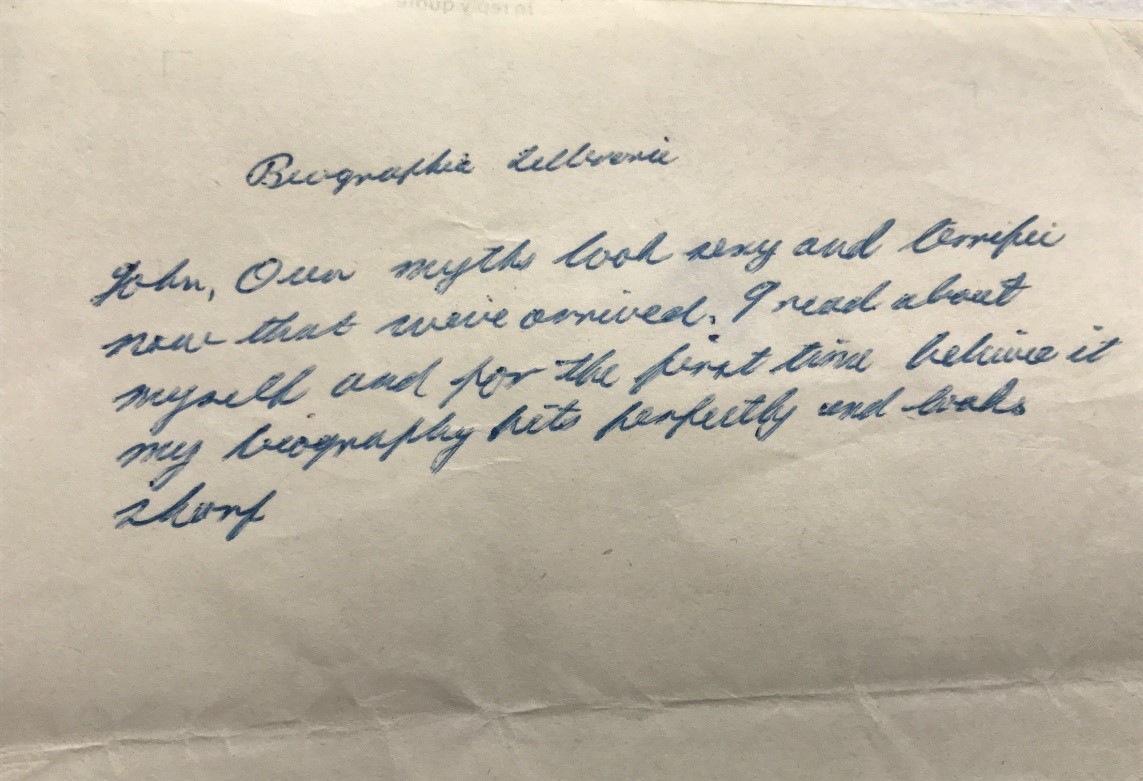

I have pursued to excess the idea of Forbes’s poetry as a practice of self-mythologising, but nowhere is this admitted so explicitly in the work. I have supposed, made rhetoric, argued, cajoled, set traps, but the closest thing to a “capture” is Forbes saying that his work is “demythologising rather than mythologising” (Redford 40) or that the poetry is “avoiding myth and message” (Collected 131). Some two months into my work as the Fryer Library Fellow I opened a folder, a fragment of paper fell loose covered in a neat scrawl:

-

Biographia Litteraria

John, Our myths look sexy and terrific

now that we’ve arrived. I read about

myself and for the first time believe it

my biography fits perfectly and looks

sharp

(UQFL 148/A)

This little bit of graffito on the walls of the archive seems a joke at my expense, and this kind of paranoid knowing (kenning) is the obverse side of an imagined intimacy or sympathy. Forbes insisted that it is the poetry and not the poet that should persist as the point of fascination, and yet here we report with glee a case of have your cake and eat it-ism. The creature turns to admire its tracks specifically as a territory-making animal in the luminous spaces of legendary biographies. The “who” of its address, “John,” the one whose written ethos “looks sharp” is the trinity of the fleshy thing holding the pen, the pricking consciousness and the ultimate prize of a golden name and created thing that supersedes mortality. The title “Biographia Litteraria” floats between an idea of the biography of a subject who writes literature and the subject being always and only a function of literature. This ploy is pinched from Frank O’Hara who pinched it from Coleridge who probably pinched it from someone else. The authorial voice here is of the one who manages identity on both sides of mortality, and which is perfectly aware of animal glamour as a fetish commodity to be distributed and exchanged, a sort of “sexy” “terrific” mask that “fits perfectly.” Is it an instance of the anthropos, the human, reading and admiring its ethos? It is struck with hubris: the pagan aficionado knows from earlier episodes that such an arch posture fetches an attendant curse.

In a letter to Frank Moorhouse the younger Forbes declares: “I lust for fame” (UQFL 148 C). This usage of “lust” has the hot shove of a Catholic terror and excitement about it, as the word “fornicator” allows us to see its horns now that it is an illustrative atavism of transgression. Anthony Domestico finds in Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poems “... an irreconcilable tension—on the one hand, the selflessness demanded by Jesuit discipline; on the other, the seeming self-indulgence of poetic creation”, a vocational quandary that applies just as well to Forbes. The dialectic of self-abnegation and self-admiration is a persistent motor of Forbes’s sensibility, the convulsive alternation of vanity and self-loathing. The self as the prize apparatus of capitalist culture is both claimed and resisted, and it is this contradictory energy that keeps his speech outside of the official organization of the polis, speaking from the pagus.[1]

Forbes’s ethos appears to possess the living through a range of caricatures that operate with an amazing consistency across his acquaintance: the poet with an unusual drug addiction, the idolizer of unattainable women, the generous and brutal critic of friend’s work, the competitive male.[2] The reductive quality of these stories is unsettling for such a complex figure, who is an assassin when it comes to sketching the bad manners and delusions of peoples and nations, yet who was sublimely delusional about aspects of his own life, while simultaneously aware of this. His mythology of himself as poet is built of beautiful contradictions: critical of nationhood yet chauvinistic, “naïve yet ferocious” (Kenneally 114), selfless and fatally egotistical, graceful in art and often awkward in person, or as Alan Wearne suggests of the ingredients of Forbes’s self-mythologising: “part hyperbole, part self-deprecation, part imagination” (128). As a figure of biographia litteraria, Forbes creates and inhabits a schizotopia where all these things are true and functional.

Both Gig Ryan (in her introduction to the Forbes Collected) and Peter Porter (at the closure of his piece for the Forbes Homage) warn us against an appetite for the poet before the poems, yet Porter’s account is a set of anecdotal nuggets showing us the quality and consistency of a “beastly” ethos: the light and dark displays of animal prestige, while Ryan turns our fetish attention back to the poems as a set of animal tracks “…of course he was like his poems, witty and brilliant” (15).

It is perhaps undesirable to separate the poet from the poetry in a figure like this: how can we fail to take an interest in the animal that leaves such beguiling traces of a total mode of being, an expert commingling of the life and the art, where the intricacy and power (puissance) of the ethos guarantees proximity to a first class daemon, and whose ambivalence toward everything: poetry, the spectacle of politics, the daemonic, romanticism, humanism, is not merely clever but exemplary. My encounters with Forbes have taken place in his poems and in those that knew him, who will often perform or ventriloquize some of his habitual gestures or sayings, and who are always compelled to ask: “did you know Forbes yourself?” noting that the ghost is now sought in me. I initially thought I wanted to hang out with the ghost of John Forbes in the archive, and the more uncanny effect of this is to realise that I am the ghost in the archive.

Rather than pursue a species of necromantics, or to fetishise the dead as dead, I want to court the daemon as a critical presence which we can cumulatively appreciate through being saturated in their compositional ethos: a style of being in language that is to be absorbed and emulated in spirit, that is, with the same insurrectionary charge. This constitutes the nachleben, the afterlife of the poet’s work, both in the recitation of the poems and a continuation of a peculiar species of intellectual spunk. I am not snakeoil selling some paranormal truth[3] by suggesting John Forbes returns to us as a daemon, but this (antique) notion has proven to be provocative in thinking about how a compelling cultural figure continues to function through their work and their myth. Peter Porter speaks of “the dangers of hagiography” (33) in any approach to Forbes, but the charisma of Forbes as a figure is enriched by including its dark matter, and so we do not require the writing up of the life of a saint but something much saltier.

What is it that Forbes’s daemon wants to transmit? When asked by Ken Bolton to contribute to Forbes’s Homage, Carl Harrison-Ford privately responds by addressing the daemon’s ability to pester:

…like many of us, I think about John quite often. It seems to me that one reason John has stayed in so many of our minds – more so than many other deceased writers of talent and influence, and amongst a wide literary and non-literary constituency – is that, in death, he lost his power to exasperate. Or that that power moved from legendary to mythical. Of course this sounds mean-minded and I offer the suggestion only as a supplement to more valuable reasons for treasuring John’s skills and memory … but it did seem to take his very real absence to sharpen/ hone a certain and precise sense of value as well as loss. (less mean-mindedly, there’s John’s intellectual and poetic unpredictability. It baffles me as much in memory as it did at the time. I can’t think of anyone else I find it so hard to second guess.

(UQFL F3806)

Harrison-Ford sketches a darker aspect of the Forbes daemon: the “power to exasperate” is recalled both for its productive negative capability (“intellectual and poetic unpredictability”) and a more cantankerous, or destructive capability. He reports a presence that is not easily accommodated with the furnishings of sentimentality but continues to offer a challenge, an opportunity for animal confrontation that pricks one to attention as in a duel. Yet the insistence upon this style of engagement is what is exasperating, and the charm falls away to reveal something of a pestering or marauding animal in your garden, whose virtue as an ally becomes ambivalent.

Forbes produces sermons that do not directly proselytise but continue to address the question ethos anthropos daemon: what can we learn of the spirit of capitalism through hunting its apparent ethos, and how exactly is it modulating and mutilating the anthropos, the human, turning it from a pack animal to a complex system of parasitism, where a few organisms exploit and feed excessively on the life forces of the whole. The daemon does not require belief: I and many others are occupied by the daemon of Forbes, as Forbes was possessed by the daemon of O’Hara, who was infected with the daemons of Rimbaud, Rachmaninoff, Apollinaire, Mayakovsky…

Life in the archive, in the forensic critical business, is weird, where intimacy with and knowledge of the writer or writing might only appear to be deepening. It is especially strange when you cannot or will not meet your subject, though he or she influences and informs parts of your own existence and animal being (and may resemble one's favourite parts of oneself). The person of the poet Shelley is remote from Forbes, and so the daemon Forbes courts is less stuck with human gristle. The smirch and charm of Forbes the animal still shows traces in the community of poets Forbes moved among. Forbes is taunting as a ghost for me, as we were alive at the same time. Forbes didn't have that with Shelley: perhaps he felt something similar for the New Yorkers O’Hara, Ashbery, Berrigan, Koch: a chronic proximity. With Forbes I’m almost stepping on his shadow, even now in Darlinghurst, or Carlton, or O’Hara’s Collected.

Having ditched totemic relations with our terrestrial friends (snake, gang-gang, gumtree) and the gods in favour of ourselves, the operation of animal glamour through stuff as a way to assert prestige has gone into overdrive. Forbes’s fetishistic relationship is with language, managing the technics of charm through the materiality of the coded song, and dressing the idea of the troubadour with new dark plumage in a time when their visibility is diminishing, as a way of producing culture that has a stake in the physical and metaphysical dimensions of being. His poetry shows a distaste for displays of animal prestige through the operation of glamour that have nothing of the sacred to them, or that which does not echo or court the daemons of our ancestors. The poetry is not preachy: it remains ambivalent in order to provoke a ritualised attention to the moment of speech, the moment of making mythos, and is not intended as a sort of spiritual hygiene or proxy religion. It celebrates poiesis as a kind of transcendental corruption, an infidel melding of the mortal and the immortal.

Keeping poems and poets as shimmering fetishes for thought feeds the desire for novelty and commodity. This is perhaps hopelessly idealistic, especially in the case of a poet like Forbes as a figure of contradiction and exasperation, but because his poems work as elusive quarry they excite a pursuit for something that stymies the acquisitive impulse. The action of transmission, of grace and the partage or communal sharing of the poet as literary daemon is what we desire and what is seemingly desired by the daemon “itself” as an old multifarious pagan “divinity.” We lose the nostalgia for a monotheistic “solution” to the variety of forms (nostalgia of the infinite) and invent instead a pantheism that makes sacred all the forms of life (nostalgia for the infinite). What is unco about the archive is that you are living among the scratchings of a legendary animal who knew how the daemonic works, but there are no secrets of ethos in the archive that might reveal more of the daemon; Forbes is immaculately consistent in his public and private work - he is his poems in a very real sense - we can contact the “ordinary” or “dirty” sublime of his life. Forbes’s sublime is not an “exalted semblance of life” to which we should aspire, but more of a human tragicomedy in which language is shown to be the source of power and transformation for the thinking animal.

By hammering this notion of sermonising, I do not mean to engrave the impression of Forbes’s poetry as a mad rout of apocalyptic chants to counteract the “bad paganism” of capitalism. A long time ear for these pagan sermons, Ken Bolton writes in his recent poem “Letter to John Forbes”:

If you were still here—or here again—you'd hop a bus

beachwards. Sydney beaches—they're still magic

& the people, the young, you'd love. I do.

It's been noted, I think, how atmospheres,

the feel of air & weather, on the skin, or thru

a T-shirt, are in your poems: sand, concrete, tar, blue

sea, blue metal, macadam, bats & moths & bugs & traffic,

perspiration, the lungs—part of the gift to us

from you—that we liked, as we read the poems,

even as we saw it as incidental. But it remains.

Bolton ends his address to the spirit of Forbes on the beach, no longer the last place you would expect to meet a spook, in a democratic gesture of love that somehow grips the perplexing and beautiful feeling of ‘being here’ spiced with the light hedonism that Sydney seems to offer through its own resident genius. The lightness of Bolton’s foot is noted as he performs a tango with Forbes’s style: the rhyming, the conceits and the steps are precisely familiar with the ethos of his dead friend’s poetry. The Forbes charis, or gift of grace, through a wicked attention to the snakeyness of the trope, is to celebrate the life of sensuality that is the body’s whole existential vocabulary. A John Forbes poem is as often subtly carnal as it is intellectual, offering a return of attention to the marvellous carcass that we are.

[1] “pagus” the latin root of pagan, indicates a small administrative territory. Lyotard seizes upon it specifically to “identify a region that has not been assimilated by consensual politics. The pagus, a border of the polity without being totally in it, is the position from which a critique of the polity can be made”. Thomas Docherty in Stuart Sim (ed.) The Lyotard Dictionary, 158. Docherty continues: “Paganism acknowledges that many gods have to be appeased, even when the gods demand contrary things of the human subject. Paganism is thus ‘impious’ … it describes a situation where ‘pagans’ can no longer subscribe to the totalizing story told by Marxism, yet still demand a form of justice.”158-9

[2] These motifs are repeated across the various accounts of the poet’s life collected in Ken Bolton’s Homage to John Forbes.

[3] though I love snakeoil

You might be interested in...