AustLit

-

The sun had beat down on the girl’s silk Japanese sunshade as she stood, early one afternoon, beneath the high verandah of the “Bachelor’s Club House.” The young subaltern, a guest among the fellows of the association, walked with his wooden supports up and down the balcony, resting only at odd moments to look across the flowering grounds.

Sumner Locke, ‘Three Chances to One’ (1916).

-

Locke’s comparative absence from Australian literary history likely has much to do with the form in which she was published. Magazine and newspaper fiction — never individually catalogued for sale or library deposit in the manner of novels or volumes of poetry — has the dubious distinction of being easily lost among the masses of printed material produced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Authors who specialised in short fiction for Victorian and Edwardian periodicals can easily vanish. For an author such as Sumner Locke, the exclusion of magazine fiction radically alters our perception of her career. Her novels, the visible, catalogued part of her output, amount to less than 4% of her total work; her short stories, as far as they have been traced, amount to over 81%.

-

Sumner Locke is only one example of an author whose known published output expands enormously once their magazine fiction becomes known. She published four novels and a handful of poems (the latter posthumously collected in In Memoriam: Sumner Locke in 1921). But her primary output was short stories: almost 100 stories have been traced in Australian periodicals between 1907 and 1917, and new stories were still being published as late as 1919. Her publications while she was living and working in England for three years remain to be traced.

Yet her modern reputation is surprisingly modest. For example, one of the very few long-form pieces to appear on Locke’s career, published by Nan Bowman Albinski in Antipodes in 1994, barely mentions her short fiction — and Bowman’s title, ‘Helena Sumner Locke: Careful! She Might Hear You’, continues the subsumption of the author into her son’s fame. One of her short stories of rural life (‘When Dawson Died’) was included in Elizabeth Webby and Lydia Wevers’s anthology Happy Endings: Stories by Australian and New Zealand Women Writers 1850s-1930s (1987), but this is a rare exception. Her association with better-known authors such as Nettie Palmer and Katharine Susannah Prichard mean that she occasionally appears in accounts of their lives and work, but her own work remains remarkably invisible.

-

The discovery of short stories has long depended on one of two events: either serendipitous discovery by researchers or the work of large-scale indexing projects. But even in Australia — which does possess a large-scale indexing project, in the AustLit database — the latter is a slow process. Digitisation projects such as the National Library of Australia’s Trove database, however, have radically altered scholarly approaches to this work, making magazine content more visible, searchable, and accessible that they have ever been — even more accessible than they were on their original publication. This collection aims to raise Locke’s profile by providing an edited subset of her short stories. Specifically, this collection focuses on one specific branch of Locke’s writing: her war-time romances.

-

From November 1914, Locke — already the author of dozens of short stories, plays, and novels — wrote a plethora of short romances that were explicitly about the continuing war. Like Locke’s other prose, the stories are bright, slick, ironic, and often brutal. They move between sophisticated urban environments and small farming communities. Some end in tragedy, some end in marriage, and some end in both. But unlike her other prose, they provide a fascinating focus on Australian women’s perceptions of the Great War.

Because Locke did not live to see the end of World War I, she never penned the elegiac post-war stories of change and reconciliation and loss that other women writers produced: stories such as Alice C. Tomholt’s ‘The Proving’ (1918), where a husband and wife explore the changes that have overtaken them in three years’ of war separation, or Capel Boake’s ‘The Secret Garden’ (1919), a ghost story that argues fiercely for the constant remembrance of the war dead. Instead, Sumner Locke’s bright-parasoled heroines and wounded heroes occupy a perpetual war, with no end in sight.

This collection is not the complete war stories of Sumner Locke, but a selection of those that best demonstrate her prose style, her over-arching concerns, and the shifts in her writing during the first four years of World War I.

-

Contemporary opinions on the quality of Locke’s prose differed. Nettie Palmer, for example, found Locke’s short stories “rather staggering”, but felt that she “had no particular direction, except to be a buster” (cited in Jordan, p.74). Katharine Susannah Prichard thought rather that Locke’s work displayed the author’s need to earn a living from her writing: in an effort to write what would sell and be popular, “little of her unordinary and brilliant individuality got into her books” (cited in Jordan, p.74).

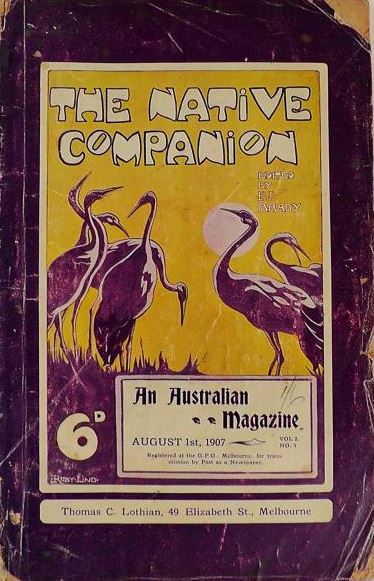

And yet Locke was working in a period when the Australian literary landscape was changing rapidly. For example, she contributed some of her earliest work to the Native Companion, a short-lived Melbourne periodical best known now for publishing Katherine Mansfield’s earliest stories. In addition to Mansfield, as Ken Gelder and Rachael Weaver argue, the periodical “drew together a group of newer women writers, whose work gave the Native Companion a feminine aesthetic more attuned to emergent forms of literary modernism”, resulting in stories that “provide brief glimpses into a character’s consciousness, rendering intensely-felt emotions and embedding themselves in the particularity of their setting”. Locke carried this aesthetic into other periodicals: one such work, ‘Broke’ (Weekly Times) is a fragment of a story, with no clear beginning or ending, driven solely by slow-rising emotional and financial desperation. The early lessons taught by the feminine modernism of these periodicals can still be seen in Locke’s war stories: the very early ‘Men’ (1914), for example, is a story of intense interiority, taking place almost entirely within one woman’s consciousness over the course of an afternoon.

-

And the “woman’s consciousness” is very much at the heart of Locke’s contribution to war writing. Unlike much war literature, very few of Locke’s war-time romances are stories of men in the absence of women. Locke’s only war story without any substantial feminine involvement is ‘Jack's as Good as His Master’ (1915), in which a station owner and his foreman begin the story arguing over the relative positions of master and man and end it sharing a common grave on the Gallipoli peninsula. Published on 4 December 1915, before Australian troops were withdrawn from the campaign, it remains one of the earliest examples of mythologising Gallipoli as the great fire in which Australian egalitarianism is forged. But it is comparatively uncommon among Locke’s work.

Also uncommon is ‘Three Gentlemen to the Front’ (also 1915), in which three young city men head out to the country for a shooting holiday, and find themselves in a world almost exclusively female: cart drivers, shoot escorts — even the sundowner who beats one of the men in a wrestling match. Each woman in the story is strong, capable, and competent, even when they do not always enjoy their work, as is the case with the sixteen-year-old shoot escort:

‘No,’ she said, in answer to his query; ‘she had never accompanied a shooting expedition before — only since her brother Bill had gone to the front. No, she didn’t like it very much — but then neither did Bill like killing — Turks.’ (p.6)

More usual is ‘Who Courts Danger’, a story of two men on the Western Front, whose relationship is mediated through the constant awareness of an absent woman, to the point where one man, pinned down by artillery fire, “could hear her cries in every mud pellet that struck his barricade”.

Stories of the front itself and stories of an exclusively feminine home front are the two extremes of Locke’s work: most stories occupy the middle space, exploring the ways in which men and women, war front and home front, intersect during an extended conflict.

-

While including some of these extremes, this collection focuses particularly on those stories that foreground the coming together of home front and war front. In these war romances, wives coerce their husbands to enlist or convince their husbands not to enlist, mothers struggle with the enlistments of their sons or with their sons’ unfitness for military service, women keep rural communities running in the absence of men, and sweethearts go to great lengths to convince their wounded lovers to marry them even after the loss of limbs or sight.

-

The mother-son relationship is evident from the earliest war romance, ‘Men’, in which a mother struggles with the enlistment of her son. This remains a common theme in the works, but Locke allows it to take different forms: ‘Mobilising Johnny’ is a more gently humorous tale, showing the aftermath when a country boy is rejected as unfit for service, but even this has a sting in its tale, as does the small-town story ‘The Dogtown Bonus’. In ‘Lines’, a struggling woman’s relationship with her restless, shiftless son improves when the war gives him focus, whereas ‘The One Shall be Taken—’ suggests that war is merely one brutal option in a brutal life.

Much of the tension in these stories is not only on the home front, but in the home itself: marriage conflict is a small-scale version of the larger debates over conscription, obligations to the Empire, and Australia’s role in the conflict. Locke’s heroines struggle against their husbands’ enlistments or strive to persuade a recalcitrant fiancé to join up. Towards the middle of the war, the stories of wounded sweethearts begin to appear: stories of women whose love is unchanged, who cannot bear the scars of war, who are trapped and devastated. For every devoted wife, there is a hopeless woman who cannot see her way forward.

Sometimes humorous but more often sharp, Locke’s war stories spring from the romantic magazine fiction of the Edwardian period, but are twisted by the constant pressure of the war, of the streams of men to the front, of the three chances to one (as one of the stories is titled) that a sweetheart would come back wounded.

-

This collection includes Locke's earliest war story, 'Men' (13 November 1914) and one of her last, 'The Dogtown Bonus' (5 December 1916). It highlights humorous stories such as 'Mobilising Johnnie' (23 January 1915) and 'The Genuine Shirker' (6 May 1916). It presents opposing perspectives on a husband's enlistment in 'Just Being a Woman' (27 March 1915) and 'The Hardest Fight' (21 August 1915), and highlights the role of women on the home front in 'Three Gentlemen to the Front' (July 1915) and 'The Eternal Softness' (5 August 1916). It includes both melodrama ('Setting the Seal', 30 July 1915) and tragedy ('The One Shall Be Taken' (14 October 1916). It showcases her courtship stories in 'Three Chances to One' (29 January 1916) and 'The Kidnapping of Lieut. Wally' (4 November 1916).

Above all, it offers an introduction to a woman who has slipped from the public record, on the centenary of her death.

You might be interested in...