AustLit

-

This section discusses the theatrical environment in which Gray's plays were produced, in terms of its effect on their writing, performance and audience reception.

-

In his surveying work, The Making of Australian Drama, Leslie Rees describes the blight of the commercial theatres of the 1930s and 40s. These theatres refused to venture productions of plays that weren't already international successes, and had no vision for a long-term investment in Australian drama. There was thus an effectual absence of established theatres available for the Australian playwright to work with – to continue refining her art as it was rehearsed and performed by physical actors on a physical stage, and received by physical audiences, in the extended process of development that was essential to those plays the commercial theatres hungrily received as 'successful'. (Rees 242-44) The Australian playwriting scene was so condemned to perpetual immaturity, or at least to amateurism, as Rees writes:

In this bogged-down state of commercial non-interest, the job of sustaining the Australian stage play was left to the Little Theatres, meaning, in Australian usage of the time, amateur groups, some of which had professional help, such as a full-time producer, and the best of which were equipped with their own regular premises. Most of the well-organised groups showed an increasing interest in Australian plays during the period 1930-50, though this usually meant only one or two in a year.

In one respect, the Little Theatres as a whole operated on the borderzone of Australia's cultural space, performing to an interested audience that composed an 'admittedly small section of the community' (Arrow 82). In another respect, the hope of an Australian drama that would determine the bounds of the homeworld lay with these theatres. These were the theatres willing to risk the work of Australian playwrights, by definition relatively little-known. Eventually, the introduction of government subsidy in 1954 through the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust brought a selection of these theatres their part in the 'institutionalisation of high culture' (Arrow 79). It must come as no surprise, then, that even the outskirting realm of amateur theatre had a borderzone.

-

An initiative of the CPA, the New Theatre was established in Sydney in 1932 as part of a league of workers' theatres, with ambitions for art as a social voice and political tool (Gabriela Zabala 188). These ambitions were to be rooted, as expressed in the constitution below, in the 'traditions' and 'aspirations' of the Australian people. Gray joined in 1938, undertaking her first work as a writer of Communist Party radio scripts, and then revues and plays (Ken Harper 63). Though the theatre was aligned with the anti-fascist attitudes of the Australian government for the first decade of its life, 1946 onwards brought public hostility upon the theatre, its most potent form being a media boycott of New Theatre advertisement and review from 1948 to 1963 – a period which included the peak years of Gray's playwrighting career (Zabala 198). The Cold War years also brought an intensifying of the CPA's own agenda and narrowing of its ranks, eventually resulting in Gray leaving the party in 1949, though her association with New Theatre continued for some years in gradually weakening form (Harper 64).

-

In addition to its political stance, New Theatre stood apart from the stream of Little Theatres in one other significant way: it employed playwrights-in-residence. Gray (and after her, Mona Brand) received with the New Theatre an opportunity available to few other women in the country. The Current Affairs Bulletin of July 1958, an issue dedicated to the history of 'Australian Drama and Theatre', gave special mention to New Theatre's interest in the development of its own playwrights:

Only one Little Theatre, the left-wing New Theatre League, has tried to train writers as well as actors. It has invited them to work backstage and onstage, to attend rehearsals of their own plays and observe difficulties and discoveries. As a result of this experience, writers have revised their scripts. This method trained talented playwright Oriel Gary to a high degree of technical competence. (49)

In this respect the New Theatre may have achieved its aims of 'developing a native drama' better than any theatre, a claim corroborated by its production statistics. 26% of the plays produced by the New Theatre between 1937 and 1955 were Australian (Zabala 193); considerably greater than the average across all Melbourne amateur theatre groups of 4% between 1929 and 1945 and 17% between 1947 and 1962 (Arrow 80).

-

New Theatre's emphasis on Australian drama was not, of course, simply motivated by a belief in the intrinsic value of a local art. It had utility; art was a weapon and words bullets. As such, New Theatre's desire to 'train' playwrights has been met with due suspicion. In a review of Had We But World Enough in the Australian Quarterly, Rees describes Gray as the 'product' of the New Theatre (125). Though he is largely referring here to her technical proficiency as a playwright, the inference that she has been built up as a creator of finely-honed propaganda is not a far-fetched one. Certainly this is the attitude Zabala takes to Gray's plays in her thesis The Politics of Drama, in which she conducts a reading of each of her plays in terms of the way they openly exhibit, or internally grapple with, CPA dogma. In demonstration of New Theatre's immense concern with the political formula of each play it produced, Zabala cites the minutes of the New Theatre Management Committee meeting that reviewed Had We But World Enough. Their advice for revision extends as far as the emphases that should be given to particular character types, the need to include working-class community members as protagonists, and the addition of a 'positive solution' that would keep the play from being a matter of 'purely personal relations' (qtd. in Zabala 182-83). Even if at this stage in her career she did not bend to them, this is at least a signal of the pressures Gray would have encountered as she matured as a playwright.

The relationship between New Theatre's two outlying qualities – its place on the political borderzone and its encouragement of playwrights such as Gray – may in fact lie in the way CPA ideology constitutes itself as a homeworld for its adherents. Within the New Theatre, political commitment counted one as resident. Yet Gray also operated from a borderzone within the theatre as a woman, and in her eventual disassociation from the CPA, and her plays reflect this. In this respect I concur with Arrow, perhaps in caution towards Zabala's approach, that it is an oversimplification to read Gray only in terms of a relation to the CPA homeland – for as basic a reason as that the 'urge to write cannot simply be attributed to political motives' (Arrow 145).

Nonetheless, Gray was a playwright of the New Theatre, even if only for the fact that it was the space in which her plays were performed. As we will see below, such a connection could have a significant impact on the life of her plays.

-

On 19 March 1952, the communist party paper Tribune reviewed the premier of Sky Without Birds at the opening of the Youth Carnival for Peace and Friendship.

-

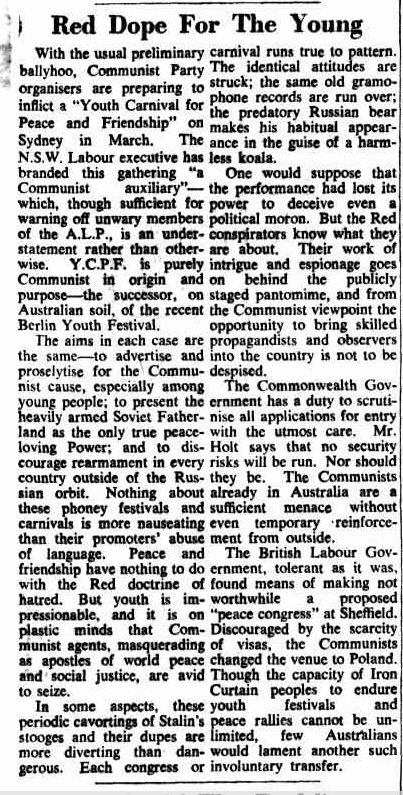

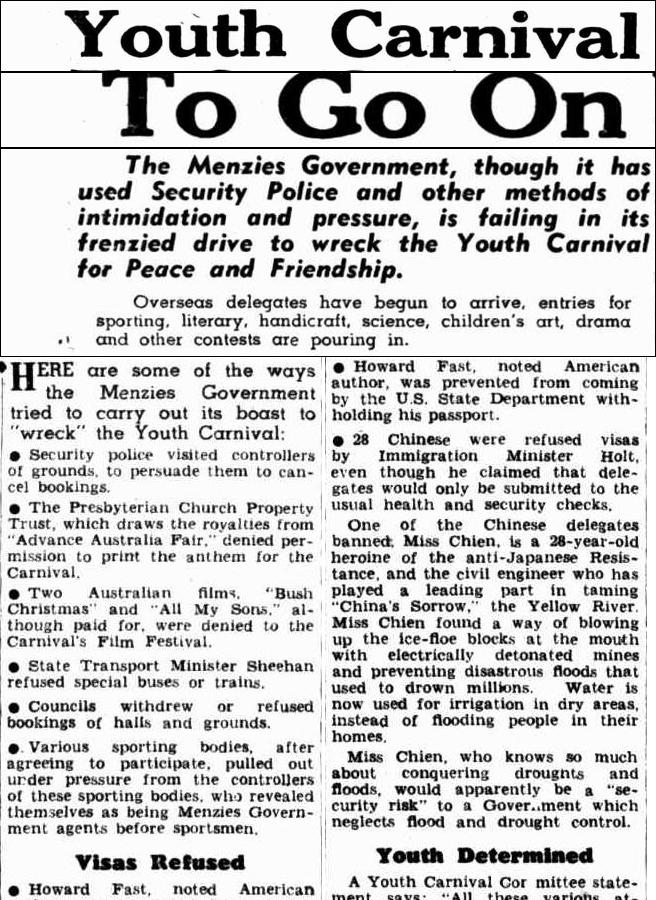

Printed in the wake of several months of heated media coverage of the impending carnival, platitudinous pronouncements of a 'packed theatre' and the 'great difficulties' under which theatre groups are performing take on renewed significance. This carnival, an initiative of the youth arm of the CPA but coordinated with a number of non-party delegates (Poynting 62), was heralded in the The Pennant the preceding January as a step toward world peace through the 'stimulating interchange of the best in the culture' of the represented countries. In the eyes of The Sydney Morning Herald, meanwhile, it was a dangerous political conspiracy for the brainwashing of the country's youth. The article below exemplifies the heated opposition directed at the carnival in the mainstream media.

-

In addition to its many sensational accusations regarding the Carnival's hypocrisy and depravity, this article makes an interesting point about the fate of Britain's own attempt at a 'peace congress'. Pressures were so high as to entirely reject it – eject it, in fact – from the homeworld by denying alien delegates entry. The inclusion of such a report insinuates that this result should stand as an example for Australia to look to in its own dealings with the Carnival. And, fascinatingly, this is almost precisely what happened – through not just the rejection of visas, but also a physical exclusion from the city centre and the symbolic heart of the homeworld. The Carnival was repeatedly refused access to parklands and grounds, finally managing to secure space in Lansdowne, a whole 30km out of the city, and only after a legal battle (Scott Poynting 67). With struggle to the very last, the Carnival did eventually take place, having found its place in the (literal) borderzone.

-

Sky Without Birds received its first production from the borderzone that was the Youth Carnival for Peace and Friendship. Admittedly, not all of Gray's plays were produced in the thick of Cold War Australia. But if a sense of the climate of suspicion surrounding any organisation associated with the CPA may be drawn from the example of the Carnival, then we may still surmise from it the nature of Oriel Gray's production spaces: firmly seated in the borderzone of the Australian theatrical and political homeworld.

You might be interested in...