AustLit

-

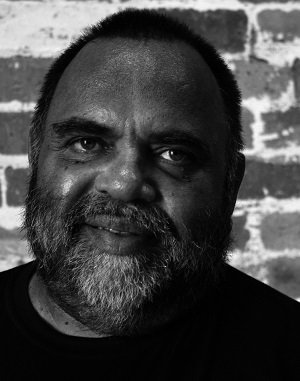

Author: Estelle Castro-Koshy

-

Estelle Castro: I didn’t notice it so much when I read The Kadaitcha Sung the first time, but I did the second time: there are three hundred pages covering only a couple of days. It is an action-packed novel, and because of many aspects in the novel – the beginning with the creation myth, the deaths of the characters (it’s got many deaths, and many depths as well) – it seems like months. This is a tour de force.

Sam Watson: The reason I structured the book that way is that Aboriginal people have a very fluid sense of time. So in our culture we don’t really look at past, present and future in a way that other people do. All we look at is an ever-evolving present with tensions and events from previous lives that have shaped and impacted upon the life we are leading now. But we’re really essentially building for the morrow so that we can hand on to our children and our grandchildren and our great-grandchildren the important things of life. So we see ourselves not as dinosaurs but as pyramids, pyramids. We see ourselves as merely passing, passing strength and we want to be able to prepare the way for those who will come after us. This is where the enormous difference between the British legal system and Aboriginal Law is. Because British law, white men’s law measures everything in terms of ownership, the right of the individual to hold and protect personal property, whereas Aboriginal Law is based on the ethic and the principle of not the individual but of the community. The whole focus is around the community needs and the community life – at all times the dominance of the community. The individual can gauge his or her worth in terms of that community context.

Thirty years ago, they first started to talk about incorporating Aboriginal land rights and recognising Aboriginal land rights within the British legal system. They were doomed from the start because British law cannot accommodate the relationship that Aboriginal people have to land, because we don’t own land, we look at land as an eternal legacy, an eternal estate that was granted to us by the Earth father, the Dreamtime spirits. And the Dreamtime spirits have charged us with this responsibility, to care and protect this sacred soil and hand it on to those who come after us. We’re guardians only. And we have a relationship with land and country, and Dreaming, that goes back in a direct Dreaming chain to the first people who one time were born and gathered at the foot of Uluru, which is the great red rock in the centre of the earth. And it’s from Uluru, which is the prime alter of Biamee, the Dreamtime serpent, it’s from Uluru that we are all connected by a Dreaming path and that’s the way we look at life. So when you look at my book and you think, well everything happens here within only two days, really what’s told is a hundred thousand years of actual history, one hundred thousand white men’s years. But to an Aboriginal person, everything we regard and we value is with us at all times.

-

EC: In your novel, the land is very much alive.

SW: It’s a living entity. It has moves, it has passions, it has tensions. You could feel that when you came up to the Glasshouse Mountains. The land felt very alive, didn’t it? Yeah, and you can feel it, and you can tune into it. And my grand-children, each one of my grand-child, I’ve got eight grand-children, I know that each one of them has a very strong link with this land. Even if they’ve got European blood as well, they still have this enormous bond with land and country, and that’s our land through three generations, through all those generations.

-

EC: And the land has a voice as well in your novel.

SW: Yes.

-

EC: Do you think it was one of the reasons it made a stir when you first published it?

SW: My writing is a direct extension of my political work. And my political work is all aimed at empowering Aboriginal people. Aboriginal people have to empower themselves to the point where they can make their own decisions without any fear of harassment or discrimination from the white forces of now that sit on our land. Even the process by which whites first came to our country. In my book, I have written that out as a direct result of a conflict between the leading Kadaitcha people, so that we have control of everything in the book. And even, as you refer to before, even the death of Tommy Gubba, that was still part of that Dreamtime process. So, Aboriginal people are in absolute control in every step of that novel. That’s another reason that it’s a different sort of book. Because a lot of Aboriginal writers tend to write of themselves as victims, and write of their characters as victims. And to me that’s bullshit. I’ve never been a victim in my life. Never have been, never will be. And neither of my characters will be either. Because there is a class of people that will lie down and roll over for the white men, but these black fellas are never going to lie down.

-

EC: Tommy is an insider and an outsider at the same time because of his mother.

SW: That’s right. He’s got an inside knowledge. But he also recognizes his mother, Fleur, has an actual culture within her blood. So each one of us, every single Aboriginal person on the face of that country does carry influence, some light influence within him. I feel sorry these so-called black radicals, black leaders stand up, they attack the so-called black culture. That sort of bullshit. You can’t do that because each one of us is a product of our environment, a product of our own bloodlines. And every one of our bloodlines contains elements of white Dreamings as well, and within Tommy’s mother’s blood flows the Aryan Celtic culture from northern Europe. So what I’m trying to say through the book, through my characters, is white Australians have the dreaming capacity within them to be able to look at land, and relate to land the same as Aboriginal people do because their cultures also led back. If only they could open their hearts, and their spirits, they’d be able to reach back to their ancient cultures as well. The Aryan cultures in northern Europe are very strong in terms of the relationship to standing stones. We have a very strong relationship with stones here with the great rock, Uluru. There is a lot of parallels between the way we look at land and culture and the cultures in northern Europe. And not only white Australians have to appreciate that but also Aboriginal Australians.

-

EC: Because of Mary’s parents, there is also African history coming into the book. It’s very interesting that it is actually a sacrilege that is going to enable Tommy to get the stone.

SW: That’s right. That addresses the need to respect other cultures and the need to not disturb other cultures, because we have characters in the book removing sacred objects and that’s a very wrong thing to do. In recent years, a lot of white tourists have gone to Uluru. And the traditional owners at Uluru have asked white people not to walk upon the rock because the rock is a very sacred place. But white people still do. A lot of white people come down from the rock and they’ve actually taken rocks and other objects from the rock. Taken them away. As time has passed, these people have had very bad things happening to them, so they felt then obliged to send these objects back to Uluru. Once these objects have come back to Uluru, and the traditional owners have placed them where they should have been, then these people, their lives have changed again for the better. So that’s a very real process and that’s something that has been commented on by a number of academic observers. We believe in that. Aboriginal people, when we walk into someone else’s country, we know that we can’t take anything from that country. Because the country is complete in itself, and you don’t take things just for sheer ornaments, and take it away to some other place. It belongs where the Rainbow Serpent placed it.

-

EC: The creation myth is written first in italics, then the story is retold at the beginning of the book. Is it a way to convey this sense of an ongoing, evolving time?

SW: Yes, it’s ever evolving. It’s always there. We see it with the italics. So we can understand it’s another party – outside of the events that are taking place – outside the book. Things that are actually taking place outside the book. You see it from two perspectives.

-

EC: Is it also to show that Tommy is going through an initiation?

SW: Yes. From the first page right through the last page, that’s his rite of passage. The book is essentially his one long initiation ceremony and he does not achieve true warrior’s state until he faces anger. It’s borrowing a bit from the biblical story about Jesus Christ. God gave the only begotten son for the world. So borrowing from that. But the Dreamtime legends predate the Christian ideology by tens of thousands of years. So we have had these stories, long, long, long time before these Bible bashing preachers from bloody southern states decided to carry out their biblical ministry. Aboriginal people have these stories and have had these experiences for a long, long time before those people started to do their business. And we own these stories. That’s what I am saying. I am drawing from things that were told to me by my uncles, and my aunties. I changed them because I don’t believe in commercialising sacred property. So it’s all fictional but just set within those borders and parameters that were told to me as a child.

-

EC: I remember you said you wrote a novel because you felt more free to write a novel than non-fiction.

SW: A lot of Aboriginal writers work in the life stories, and that’s fair enough because a lot of these people’s stories have to be told. Last year and the year before, we saw the enormous impact of the Rabbit-Proof Fence. Aboriginal stories, Aboriginal lives have to be shared with the broader audience and they can have a great impact and be very, very important and become part of the national ethos, and also build blocks towards true reconciliation. But me as an artist and as a writer, I feel much more comfortable in working with fiction, because this has got huge license. I can do anything I want and this is again an expression of my seeking empowerment. I feel far more powerful and in control of fictional characters and fictional settings than I would if I was writing someone else’s life story. So I recommend it.

-

EC: I also remember you said that every Aboriginal work is a political work. So do you think the novel carries its own form of politics?

SW: Everything we do is a political act. Although a lot of Aboriginal people who are far more conservative in their perspectives and outlooks would deny that. Everything we do on the face of this country is a political statement. Even not doing anything, even being totally passive is still a political statement, and people don’t accept that.

-

EC: Do you think that through your novel you’re keeping the heritage alive as well?

SW: Never intended. Because as I said it’s not a true heritage. This’s just my fictionalised perspective on a Dreamtime story. That’s all it is. It’s Dreamtime story, it’s a yarn. An adventure story.

-

EC: Your book also brings out many issues. Like the issue of language. In the novel, ‘Tommy […has] to revert to a form of pidgin English to convey the concepts of migloo justice’. English is the language of power at the same time as—

SW: We use that as a fence mechanism where we can climb behind. Within, across Australia, before James Cook came here, before 1788 when the first fleet arrived, there were five hundred tribes living on this country; that’s five hundred separate autonomous totally independent nations, living side by side and each tribe has its own language or dialect. But with the coming of white men we had this conqueror language enforced upon us, this language of English. A lot of cultures and a lot of languages, a lot of it has been destroyed, and a lot of our elders tell us that when they tried to talk their own languages, and dance their own dances, and sing their songs, and tell their stories they were punished severely for it, because the whites were trying to civilise the so-called primitives, primitive blacks. Trying to bridge the gap between Aboriginal culture and English culture was this non-standard English, non-standard language. So that it has a little bit of Aboriginal in it and a little bit of standard English in it. But it’s our language. It’s a dialect, a lingo that can be shared by Aboriginal people from wide across, you know, from white country to Aboriginal people from many, many hundreds of miles away. So, we can talk to each other in language, we can understand this pidgin sort of English. That works for us. Actually, there have been white academics who have explored this language, written about it, and documented it. This is not great mystery to us. It does seem to be understood. But also, one of the difficulties I find when talking about languages is that so much communication between Aboriginal people is non-verbal communication, so that’s the difficulty. Because we can sit side by side and exchange millions of pieces of information without ever giving voice to one word. Aboriginal people use hand language, Aboriginal people use eye contact, body movements, so there is a lot of different ways of communicating without having used spoken English or spoken tongue.

-

EC: That’s one of Tommy’s strengths in the novel, he is really able to adapt.

SW: He flies between the different worlds. That’s why I wanted him to have mixed blood, to have two bloods. So he wasn’t absolutely Aboriginal. I wanted him to be torn between those two worlds. Also to be torn between the different strata of Aboriginal society, so at one stage he is the so-called educated employed person but he’s mixing in the pubs, with the so-called drunks, these sort of people. That’s a very real thing as well because Aboriginal society is not just a single homogeneous mono-class that has, that shares all common attributes. Aboriginal people also have a very complex social system and social structure in place, where you have at the top a very – particularly now, in 2003 – you’ve got a very strong middle class of educated blacks of upper grade public servants – so very wealthy. Then down at the bottom of the line you still have the park people, the homeless people. In the middle you’ve got the great majority of Aboriginal people living on government benefits. So you’ve got to be able to look at a society like that. And a character like Tommy walks through that society. But he’s recognised and has knowledge.

-

EC: But it’s neither black nor white in your novel.

SW: No, no, because…

-

EC: Because even the Gods are—

SW: Frauds. They’re frauds. Because I mean, that’s life. A lot of people depend only on the forces of heaven. But as the Chinese people say, sometimes you can petition the Gods, but sometimes the Gods might be sleeping, you know. And Aboriginal people can’t sit back and say: ‘I’m going to sit in this park and get drunk, because that’s what life has intended, and if the Dreamtime gods are going to lift me up they’ll come and get me.’ You can’t do that. You’ve to get out there, stand on the front of your feet and make your way. You can’t, you can’t throw it back on the Gods, because at the end of the day the Gods are also frauds, fraud characters, they’re tainted by events and happenings and this is very much within the Christian concept of God as well. God is a very violent person, this God that they worship. When I was young I was reading the Bible in the Sunday school classes and I found this God who expected this fella to kill his child. What sort of God would expect a parent, demand a parent: just rise up and kill his two or three year old boy. That’s bullshit, that’s totally unacceptable. I couldn’t imagine that happening. It could not happen. It could not happen. Also, the Bible is very male dominated, a male dominated story. So I thought that’s the reason why there are so many parallels between… Aboriginal culture is very male dominated. And Christian culture is very male dominated. It took ten centuries before women were allowed to preach in certain churches, within certain places. And that’s unacceptable too. And even in the Aboriginal community, women play a subservient role, and that’s not acceptable either. Because, you really have to empower. And Tommy defied his Gods by impregnating Jala. He was tempted to take Jala with him on his journey of empowerment.

-

EC: You also said that when you wanted to have your book published you sent it to Penguin.

SW: Yep.

-

EC: And you didn’t want to send it to any other smaller—

SW: No.

-

EC: As a way—

SW: As a challenge. I asked around. I thought: I have this manuscript. So I asked around to bookshops. I asked who is the biggest publisher in Australia? They said, ‘oh Penguin’. That’s the best publishing, biggest publishing house in Australia. I sent it off. Yeah.

-

EC: Why is the class that you’re teaching called Black Australian Literature and not Aboriginal Literature? Is there a reason for it?

SW: Because there is a small class of writers in Australia who are not Aboriginal, not Torres Strait Islander, but are people of colour whose work and whose lives are very parallel to the Aboriginal situation. Writers like Roberta Sykes. Her mother was white Australian, and her father was a black American serviceman. She was mistaken for an Aboriginal woman by a group of young white men. She was pack-raped when she was a young woman by this group of white men, about 18 in all. Because they thought she is Aboriginal. They were carrying out this act of rape against a woman they thought was Aboriginal. They were punishing her for being Aboriginal while in actual fact, she wasn’t Aboriginal at all. But she paid for that. And she exposes the issue of rape through her book Snake Cradle which was the first book in her trilogy. So what I try with my courses is to broaden my students’ understanding of what it is like to be black within Australian society from both points of view. I thought it would be a benefit if some of my students chose to read writers like Roberta Sykes, who is neither Aboriginal nor Torres Strait Islander, but who have lived their lives within white Australia, being settled with the Aboriginal yoke as it were.

My decision to call the course “Black Australian Literature” was also a mechanism to avoid those enormous debates about the fringe writers who were being challenged about their identities. At that time we were constantly reading about writers like Sykes, Mudrooroo, Weller. I’m not afraid of being involved with those issues; but I still wanted to look at some of the work by those writers. I was not in any position to make definitive decisions about their true right to regard themselves as Aboriginal writers.

-

EC: I don’t know if you remember… The senior editor of UQP said, when she came to your classes, that Anglo-Saxon writers are too self-conscious, and that compared to them… Aboriginal writers are very powerful, because they’re not too self-conscious. She also said that for Anglo-Saxon writers, the truth is remote and they don’t cross over different genres. Would you say that Aboriginal writers are not self-conscious, or would you say that they are conscious of something else?

SW: I think Aboriginal storytellers have a more developed sense of audience. I think it’s easier for Aboriginal writers to make that big step towards writing their books. Whereas I think white Australians essentially grew up in an island in a very wide sea and don’t have the same sense of community and history as Aboriginal people. Aboriginal people also have this vast heritage as storytellers to rely on. Whereas white writers, emerging white writers have to develop those skills and earn their senses as storytellers. I think Aboriginal writers have a lot of advantages but also Aboriginal writers have great disadvantages as well. Because white publishers still don’t regard Aboriginal writers as being commercial writers, actually commercially viable. So there’s still a lot to travel. But it’s interesting, interesting to listen to people like Sue Abbey who has been so involved with black writers and she feels very comfortable with working with Aboriginal artists. I think it’s best not to generalise too far.

-

EC: You said that the David Unaipon Award is the only literary competition where the jury members – and you’re a jury member actually – make comments for every entry. Do you have any idea of why that is?

SW: Why we, why the judges?

-

EC: Yeah...

SW: Just to encourage. Encourage the writers. Every publishing house in the world receives hundreds of unsolicited manuscripts and offerings every year. And very few people, very few of the contributors ever receive any sort of acknowledgement or assessment of their skills. I’d say 98 percent of people who send manuscripts in receive very terse, very short letters saying ‘not good enough’, ‘thanks anyway’, ‘see you later’. But with us we think the Unaipon is a great opportunity for us to nurture and bring forward emerging and developing voices. We try to give our mob as much encouragement as possible. That’s the reason why we give at length the response on what we thought of the work. It’s not all rosy. We can be quite critical of the work because it’s important that the people don’t think: ‘right I’m Aboriginal, and I can tell a story, that’s it.’ It’s a long hard road to write and write well. It’s an even harder road to find a publisher who is going to take a gamble on you. It’s important that people understand that. You can’t just wrap people in cotton wool and think you’re doing the right thing by them because other people have to be told they’re never going be a writer in a million years. If they’re interested in the genre, interested in developing the skills of writers, the great majority of these people will be well served to become involved in local writing groups and discussion groups, and just find out how the writers present their works, and what challenges they face. A lot of people out there have this very romantic idea that they’re going to write the great Australian novel. They’ll do it in three months. Bang bang bang. Throw it to a publisher. Bang bang bang. The publisher will pick it up, then someone from Hollywood comes along and pays 50 million dollars for movie rights. That would happen to one in one million writers. As I said, it’s a long hard road. If we’re going to use competitions like the Unaipon to encourage and nurture developing voices, we also need to present a certain rigidity and discipline in our appraisal, so that people know that if they’re going to succeed and they attempt to become published, they’re going to put the hard yards in.

This interview was conducted on 19 June 2003 in Brisbane.

-

This image has been sourced from WebSee full AustLit entry

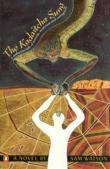

This image has been sourced from WebSee full AustLit entry"The Kadaitcha Sung tells the story of Tommy Gubba, son of Koobara, son of the chief of the Kadaitcha clan, and Fleur, a white woman, of Northern European descent. Tommy was born secretly after his uncle Booka Roth killed his father to become the last of the Kadaitcha clan. The Kadaitcha clan is in the novel an "ancient clan of sorcerers" (1) called by Biamee to stand among the tribes of the South Land (i.e. Australia) when he returned among the stars. Tommy is initiated and called by Biamee to recuperate the heart of the Rainbow Serpent stolen by Booka Roth, without which Biamee cannot "complete his earthly manifestation".

(...more)

You might be interested in...