AustLit

Latest Issues

AbstractHistoryArchive Description

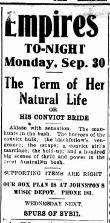

Bess Shelgrove is framed for theft after refusing the advances of bank clerk Adam Wilson. Transported to Australia, she meets and marries Jack Warren, but their marriage is not without difficulties until Warren forces Wilson to confess to his theft.

Notes

-

The title was changed from For the Term of Her Natural Life after Marcus Clarke's daughter threatened legal action.

Publication Details of Only Known VersionEarliest 2 Known Versions of

Works about this Work

-

Lost Adaptations : Piracy, ‘Rip Offs’, and the Australian Copyright Act 1905

2017

single work

criticism

— Appears in: Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television , vol. 37 no. 2 2017; (p. 161-173)'In this article, I want to historicise the study of Australian film adaptation by concentrating on the Copyright Act 1905, which during the nascent industrialisation of patent and copyright law did not recognise celluloid pictures as matter that could be copyrighted. Consequently, with the Act formed to provide authors greater powers to stop the proliferation of degraded versions of their work, film-makers saw adaptation as a strategy to legally protect their moving pictures from copyright infringements. By concentrating on Australia’s early industry of feature film production, it becomes apparent that through adaptation, and through the ability to copyright film as adaptation, there was a strong incentive in this formative period of Australian film production to adapt popular history tales drawn from the literature. And it was through this 1905 Act that the tradition of Australian adaptation and tradition of adapting historically set works began.

'While such an approach is necessary for this study, which concentrates on ‘lost’ feature films, the idea is to consider all forms and types of past and present adaptation as a way to encourage and advance its study. Here, I hope to gain some sort of understanding of how these literary works were being adapted, and socially consumed by its film-going audiences. This approach does not rely solely on a film’s source of adaptation or any one particular film. Instead, it places it within legal discourses of cinema activities including distribution, exhibition and marketing. By concentrating on the Australian cinema’s dedicated tradition of adaptation, during the silent period of film production, in this article, I will discuss how filmgoers at, and outside of, the cinema were encouraged to engage with feature films as adaptation – and what this culturally meant. In doing this, I hope to establish how Australian film adaptation began as a means to copyright a film from piracy and plagiarism ‘rip offs’.'

Source: Abstract.

-

Lost Adaptations : Piracy, ‘Rip Offs’, and the Australian Copyright Act 1905

2017

single work

criticism

— Appears in: Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television , vol. 37 no. 2 2017; (p. 161-173)'In this article, I want to historicise the study of Australian film adaptation by concentrating on the Copyright Act 1905, which during the nascent industrialisation of patent and copyright law did not recognise celluloid pictures as matter that could be copyrighted. Consequently, with the Act formed to provide authors greater powers to stop the proliferation of degraded versions of their work, film-makers saw adaptation as a strategy to legally protect their moving pictures from copyright infringements. By concentrating on Australia’s early industry of feature film production, it becomes apparent that through adaptation, and through the ability to copyright film as adaptation, there was a strong incentive in this formative period of Australian film production to adapt popular history tales drawn from the literature. And it was through this 1905 Act that the tradition of Australian adaptation and tradition of adapting historically set works began.

'While such an approach is necessary for this study, which concentrates on ‘lost’ feature films, the idea is to consider all forms and types of past and present adaptation as a way to encourage and advance its study. Here, I hope to gain some sort of understanding of how these literary works were being adapted, and socially consumed by its film-going audiences. This approach does not rely solely on a film’s source of adaptation or any one particular film. Instead, it places it within legal discourses of cinema activities including distribution, exhibition and marketing. By concentrating on the Australian cinema’s dedicated tradition of adaptation, during the silent period of film production, in this article, I will discuss how filmgoers at, and outside of, the cinema were encouraged to engage with feature films as adaptation – and what this culturally meant. In doing this, I hope to establish how Australian film adaptation began as a means to copyright a film from piracy and plagiarism ‘rip offs’.'

Source: Abstract.

-

cAustralia,c

-

cEngland,ccUnited Kingdom (UK),cWestern Europe, Europe,

- 1813