AustLit

-

Marita Bullock and Nicole Moore

Introducing Australia's Bibliography of Banned Books

In March 1935, the Minister for Trade and Customs Thomas White informed the Australian Parliament that: '[a]ny importer of books can get a complete list of those books which are banned' (Parliamentary Debates No. 146, 354). His department, under the powerful Trade and Customs Act of 1901, was responsible for the administration of federal censorship for most of the twentieth century. It could prohibit the importation into Australia of publications (and goods) deemed obscene, indecent, blasphemous and seditious, or those identified to excessively emphasise sex, violence or crime. It was remarkably successful in this endeavour. Customs felt little responsibility to inform the Australian public about what was banned, however – rather the reverse. Despite Minister White's assertion, for many decades it was difficult for anyone outside the department to discover just what was proscribed reading for Australians, or to delineate just what it was that kept books or other publications out of the country and out of the reach of curious Australian readers. The banned list was secret.

-

-

When White addressed Parliament in 1935, as Customs Minister in the conservative UAP government of Joseph Lyons, the list of publications banned by Customs as prohibited imports had been active since the first decade of the century. It was implemented as part of Customs' important role in the careful and protective government offered to a newly federated, no longer colonial nation. As Customs General Order 890, the banned list was circulated internally within the department but deliberately not released to the public. Australians were prevented from knowing what publications were being kept from them until 1958.

A secret list

Minister White's assertion that the list was available to importers was only partially true. The department offered a copy of it to Albert and Son, Booksellers, Perth, in February 1933, for example, but the importer declined on the grounds that, as Customs reported, 'its possession would be to their disadvantage if it so happened that through an oversight they ordered a book which was on the list'. In response, Albert and Son were advised that they would be responsible for any importations in breach of the Act whether or not they held the list (NAA A425 1943/5280). Often, however, importers had to enquire individually to the different State Customs Collectors for the admissibility of any title (Payne 10). White's statement fudged department policy and suggested a regime much more open than it was under his direction. A year later, in reply to a request for the list from the Worker's Education Association, which in September 1936 was importing 500 books a year, a Customs official wrote: 'It is not now the practice of the Department to supply lists of prohibited books to the public and it is therefore regretted that your request cannot be approved' (Payne 10, NAA 70/06107).

Customs was defensive about how the list would be employed: not only to generate demand for banned books but to bring the department itself into disrepute. Customs Clerk T. B. Simons had advised the Comptroller-General, the Department's permanent head: 'There is a very keen desire on the part of certain organisations to obtain a list of the prohibited books and if they could obtain copies there is little doubt that the lists would be used to criticize the Department' (Payne 11, NAA 70/06107). Leader of the Opposition John Curtin wrote to White requesting a copy of the list in November 1936, and White replied that while he could not give him a copy, he 'would be glad to let you see a list at any time at my office' (Payne 11, NAA 70/06107).

Continuing criticism flared into questions in Parliament in April 1946, after Customs officials had seized doubtful books from a Sydney library and as police proceedings began against Australian author Robert Close in the Victorian courts (Day, 267-8). In a question without notice, Labor member Leslie Haylen asked about Customs' refusal to publish the list of prohibited publications. Acting Minister John Dedman in the Chifley Labor government responded that this was 'because this course of action would give the books undue and undesirable publicity' (NAA C4480 Item 23). Dedman called for a report from Customs on the policy, provoking an internal protest by the Assistant Comptroller-General of Customs, Bill Turner, who criticised the practice of withholding the list and called for a review of the banned list.

Comptroller-General J. J. Kennedy responded forcefully:

The Department has a definite duty to protect the morals of the community by exercizing censorship ... and after 40 years experience in the Department I would say that the need is as great today as ever. There is an insidious campaign to glorify promiscuity and make light of sexual offences. This must react unfavourably on immature minds and does, I fear, create desires which lead to unnatural offences.

He continued:

I do not think that the meanings of the three adjectives [indecent, obscene, and blasphemous] have altered since the Act was framed. Consequently if a book was 'indecent' in 1905, it should still be 'indecent' if the objectionable matter still remains in it.

No wholesale revision of the list will be undertaken voluntarily by the Department (NAA C4480 Item 23).

Kennedy served a relatively short term as Comptroller-General, from 1944 to 1949, but he drew on his long service with the department to assert so confident a knowledge of indecency in books. Over seventy-two years, Customs grew up a civic bureaucracy whose business it was to know a dirty book when it appeared, and to keep it from the rest of the country. As Turner had predicted, however, the banned list was soon leaked - an outdated list of 'the books the Australian public has been forbidden to read' was published by the Bulletin on 8 May, 1946 (cf. Day 268).

A revised list

It was not until 1958 that the first 'wholesale revision' of the list was undertaken nor was the list officially released outside Customs until 178 titles were published in the Commonwealth of Australia Gazette in that same year (No. 23, April 24, 1958). These represented only a portion of the total number of banned books, even then. The gazetted list included only literary or scholarly titles whose prohibition was deemed to be of public interest: the majority of titles, whether pulp, low brow, ephemeral or unashamedly pornographic, were not published. Until 1958, any publication could languish unknown on the banned list without recourse, until it fell out of print, unless a publisher or distributor could persuade Customs to consider a title individually.

The momentous events of 1958 were occasioned by a review of censorship undertaken by then Minister in the Menzies government Denham Henty, and he had been stirred to action by a scandal over the banning of J. D. Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye. A copy of the book, held up internationally as one of the best literary products of the US from the 1950s, had had to be removed from the parliamentary library in September 1957 ('Withdrawal of Book', cf. Coleman 35). Without the knowledge of the parliamentary librarians, the book had been banned by Customs officials a year before (NAA C4129/1 Box C). Without recourse to either scholarly expertise or community standards, a book respected around the world, even donated by US ambassadors to foreign libraries, had been refused entry to Australia (Coleman 'Letter'). Its prohibition was a secret, as were all book bans until one infringed one, so the uninformed librarians had displayed it for the edification of the nation's elected representatives. Indeed, it had been circulating in Australia since its publication in 1951.

Even in 1970, in their edited book attacking Australian censorship regimes, a continuing lack of transparency meant Geoffrey Dutton and Max Harris condemned as an issue of civil rights the fact that the public was not fully informed about what it could not read. 'We refuse to be prevented from knowing what is banned and what is not banned' they declared. 'We must possess the civil right to test the competence of the banners, the consistency of standards, the application or misapplication of laws which may be good, indifferent or rotten' (Dutton and Harris, 7).

The bibliography

Banned in Australia is a bibliographic list of every literary title banned by Customs censorship through the twentieth century. It begins from the passage of the Customs Act in 1901 and ends in 1973, when the Whitlam government reduced the banned list to zero. In effect, this bibliography reconstructs the banned list for the first time. Described by David Marr in his Patrick White biography as an 'index of Australia's innocence' (501), the banned list is a catalogue of titles that now shows us the limits of Australia's experience of the world. Bringing it into public view allows us to see not only that which we have been prevented from seeing, or reading, but the frame through which censorship delimited that view - the rationale and limits of proscription. The banned list indexes what we didn't know, and thus throws into illuminated relief what we thought we did.

The Banned in Australia bibliography is the first to provide reliable historical and bibliographic information on the federal prohibition or partial restriction of literary publications banned for importation into Australia through the twentieth century. The bibliography contains bibliographic and historical information about almost 500 titles. For the first time, the Australian public has an accessible and reliable index of the 'literary or scholarly' books that were banned, with detailed information about the dates of a book's banning and release from prohibition, in addition to bibliographic details of the editions that were banned. In some instances, the bibliography also reproduces quotations from individual censors' reports on titles, which furnish the record with detailed insights about the reasoning behind a book's prohibition or restriction.

The impact of publications censorship has been well-charted in non-Australian contexts, with numerous online and print bibliographies detailing titles banned across the centuries in different countries and distinct instances. Indeed, there are too many banned-book bibliographies to list in any comprehensive way. Alec Craig's The Banned Books of England, first published in 1937, was employed by Australian censors themselves, when re-banning Joyce's Ulysses in 1941, before Craig's book was updated as The Banned Books of England and Other Countries in 1967 (NAA C4480/1 Item 23). Since then, notable enumerative and descriptive bibliographies have collected titles banned from the UK, US and Europe and catalogued the holdings of the closed case collections of the British Museum, the Bibliotheque Nationale and the Library of Congress, and other national libraries. Recent online collections of the banned books of South Africa and Canada provide particularly revealing comparisons for settler Australia (A Chronicle of Freedom; Jacobsen Index). The Banned in Australia bibliography is the first reliable index of books banned in Australia specifically, offering new insights into the national practice of censorship and contributing significantly to the developing transcultural scholarship on censorship in different parts of the world.

The compilation of the list of banned titles has been no small task. Absences, disavowals, omissions and sometimes baffling bureaucratic processes are a defining feature of the records of Australian censorship practice. The Banned in Australia bibliography relies on the records collected by the various federal government agencies who had responsibility for censorship at one time over the century or whose ambit included some aspect of censorship. Customs provides the largest cache of records - almost 70 file series in the National Archives, some of which measure shelf space of up to 200 metres. The Attorney-General's Department and then the Office of Film and Literature Classification inherited Customs' censorship role and collected substantial records, and records from the Postmaster-General's Office, ASIO and its predecessor the Central Investigations Bureau, and the Office of Prime Minister and Cabinet are also illuminating. We have sorted through fragmented, unregistered and often contradictory archival records housed in the National and State archives in Sydney, Melbourne, Canberra, Brisbane and other capitals.

The project has taken three years to complete. It was begun by Monique Rooney and Nicole Moore in June 2005 as an outcome of Nicole Moore's Australian Research Council Discovery Project on twentieth-century Australian literary censorship. Marita Bullock took over most responsibility for completing the project, with Dr. Moore, from May 2006 to completion in June 2008. Across the three years, we generated information on 500 literary or scholarly titles that were banned or restricted by Customs censorship across 1901 to 1973.

The bibliography aims to include every one of those titles. It is delimited according to the censorship practices carried out by the specialist literature censorship boards that functioned under Customs' powers in that period. In response to public protest, these boards of review were established in order to provide expertise on works with claims to literature or scholarly merit, which before 1933 were banned by Customs or the Minister himself without recourse to expert or community opinion. After 1933, Customs remained responsible for administering the bulk of imported publications, including pulp fiction novels, all forms of erotica, underground pornography, magazines, comics and some art books.

The titles of merit that required expert knowledge were forwarded to a panel of literary or legal experts, and their main task was to establish whether a title had enough literary or scholarly merit to exempt it from being banned or restricted for the public. Books were evaluated according to whether their style and content exempted them from the charges of obscenity, indecency or blasphemy under Section 52(c) of the Trade and Customs Act. These charges were later adumbrated by a separate clause that specified an undue emphasis on matters of sex, crime or violence, in a manner calculated to encourage depravity, introduced in 1938 under Item 14A of the Second Schedule of Customs (prohibited imports) Regulations. The boards were changed three times through the twentieth century. The first censorship board was named the Book Censorship Board, and it functioned between 1933 and 1937; the second board was titled the Literature Censorship Board, and it operated between 1937 and 1967, and the final board was called the National Literature Board of Review, and this board of experts administered literary titles between 1967 and 1973.

Literary boards

The activities and decisions of the literary boards have been central to the way we have structured the bibliography. We have used the central principles that organised censorship during the years that the boards functioned to define the dataset's key terms. Because the bibliography only collects literary or scholarly banned books, it is restricted to those banned titles that were sent to the specialist literary boards for expert review: in effect using Customs' own definition of the literary or scholarly. This means that the great majority of censored works included in the bibliography are imported publications seized by Customs officials from points of arrival into Australia and forwarded onto the literary boards for expert evaluation. The restriction to federal censorship administered by Customs means that the books included in the bibliography are almost all non-Australian publications and are distinct from domestic books prohibited under state censorship legislations. The bibliography also excludes publications banned by the federal Attorney-General's Department as seditious or refused registration for passage through the post by the Postmaster-General's Office.

The information included for each record within the bibliography reflects the functions of the panel of literary experts. It specifies whether a book was banned by the board or restricted in its circulation, and it supplies a date for the book's prohibition or restriction. A publication that appears on the dataset with a banned icon means that the work was entirely removed from the public, whereas a title with a restricted circulation sign means the title was banned to the general public with the exception of those students or professionals who could demonstrate scholarly expertise to access it. The kinds of titles that were typically restricted in their circulation are medical studies, particularly those focused on human sexuality, reproduction or birth control, or anthropological studies in sexual practices.

In addition to specifying the title and the date of that title's ban or restriction by the board, the dataset may also include a few sentences from the board members' reports relating to the rationale given for a book's prohibition, but this extra information is not always available and it is only included if the censor's report is noteworthy or in some way representative. Furthermore, the dataset may also include information about when a book was sent to a board for review of its prohibition and whether the review process resulted in the maintenance of the ban or whether it entailed the book's release. After 1958, reviews of the banned list of literary titles were carried out first on a nominal five-yearly basis, but later annually or more often even than that, and in a systematic fashion. Before and after 1958, reviews of bans on individual titles were also sometimes prompted by requests from publishers, importers or the public. The dataset includes information about a book's release from prohibition or restriction if it is available.

Exceptions

Some of the dataset entries include a note stating that the board's review resulted in the book's reclassification as non-literary, or straight pornography, and its subsequent removal from the list of gazetted works of literary or scholarly merit. This meant that the publication remained prohibited but was removed from the public record of banned books, and its prohibition was then administered by Customs officials rather than a board.

The dataset provides verified bibliographic details of each publication, including the title, publishing details and date, usually furnishing at least the edition of the title that was first prohibited or restricted by the board. It also provides brief biographical information about the authors of books where this information is traceable. The author's date of birth, nationality and key information about the author's writings and/or historical significance allow researchers to distinguish banned international authors from the Australians included in the broader AustLit database and to draw some conclusions about the nature and sources of the banned material.

There are some titles within the bibliography that exceed the key terms: 'federal censorship', 'Australia 1901-1973', 'literariness' and 'banned' or 'restricted'. These exceptions demonstrate both some of the key questions at stake in the administration of federal censorship as well as some of the limitations faced by our endeavour to reconstruct its activities. To begin with, there is some difficulty establishing firm parameters for the time period of the bibliography. While the bulk of records documenting prohibition have been sourced from within the time period during which the specialist literary boards functioned - between 1933, when the Book Censorship Board was first established, through to 1973, when the National Literature Board of Review was nearing its demise - this time span (1933-1973) does not adequately describe the history of literary censorship through the twentieth century.

Previous influential histories of Australian literary censorship have argued that prior to 1929 few literary titles were prohibited, Peter Coleman asserting that in 1928 'the complete list of banned works of literature was made up of three books' (14-15). This conclusion seems to have been reached on the basis of the paucity of Customs records, however, rather than on positive evidence of a more liberal practice. Coleman himself suggests that Customs records were destroyed on the move from Melbourne to Canberra in 1927 (237) and Ina Bertrand's history of Australian film censorship records a destructive fire in the Sydney Customs House in 1926, where much censorship administration was conducted (52). New work such as Deana Heath's attends to evidence of Australia's involvement with international agreements to prohibit the circulation of obscene publications in 1910 and 1923 as a measure of Customs' activities (Heath 'Creating the Moral' 165, NAA 981/4 LEAGUE OBS 3). Stephen Payne has collected copies of Customs General Order 890 from 1909, 1927 and 1929 and each list counts 7, 45 and 129 prohibited publications respectively (2). It seems clear from the remaining evidence of administrative practice that Australian Customs censorship continued in the decades between the passage of the Customs Act in 1901 and the banning of Joyce's Ulysses in 1929, although with less distinction between the literary and non-literary than was ordinary in later decades.

We have found evidence recording some literary titles prohibited by Customs as federal imports prior to the establishment of the Book Censorship Board in 1933. In 1912, a consignment of 30 cheap editions of Gustave Flaubert's Madam Bovary, Theophile Gautier's Madamoiselle du Maupin, and seven other titles, mostly French, were refused entry into Launceston, with reference to General Order 890, and confiscated, for example (NAA P437/1 Item 1912/1710). In a memo to all state Customs Collectors on May 25, 1923, regarding The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio, the Deputy Comptroller-General directed that 'it is intended to enforce the prohibition against cheap editions of the work only and not against the expensive sets imported for genuine literary purposes' (NAA P437 Item 1922/678). So an abridged edition called The Little Decameron was passed in June 1923, but another new edition was banned in May 1930, and cheap editions of The Decameron remained banned until it was referred to the Book Censorship Board, who passed the title for import in 1935 (NAA A3023 Folder 1935/1936, "Decameron" Banned'). It is one of the three titles included in Peter Coleman's list for 1928.

Our inclusion of such titles in the bibliography has been imperative to the task of generating a complete and reliable documentation of literary censorship across the twentieth century. Nevertheless, the bibliography's information on titles banned between 1901-1933 is scanty and far from complete, since archives in Canberra, Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and Hobart have not yielded systematic records for book censorship during that period. We cannot confirm that Madam Bovary was a prohibited import into Australia in 1912, for example.

Furthermore, the delineation of the bibliography to the year 1973 is also provisional. We have ended the bibliography then because by the end of the first year of the Whitlam government, the list of banned records was reduced first to five and then to zero titles (NAA C4371/1 Box 1 Folder 8). Records also document the winding up of the National Literature Board of Review at the end of 1973. Publications censorship was administered by the Attorney-General's Department from the early months of 1973 (C3059/1; Box 152-154), in a transfer of Customs' functions but not powers that was facilitated by the fact that Senator Lionel Murphy held both portfolios. Certainly literature never again held the position it had maintained as the flashpoint for public protest about government censorship before the early 1970s, even as the list of banned publications again increased after the demise of the Whitlam government and the later establishment of the Office of Film and Literature Classification in 1988. After the early 1970s, by far the majority of items censored have been popular media, such as magazines and video, and this continues to be the case in our current classification scheme.

What is 'Literary'?

The concept of the 'literary' is another of the fluid and contestable terms around which the bibliography has been organised. By compiling the dataset in association with the definitions of the literary that have been employed by Customs and the specialist literary boards of review, the dataset reflects the somewhat idiosyncratic ways in which the literary was conceived by Customs officials and board members. Indeed, Customs' concept of the literary does not always correlate with scholarly conceptions of literature, or even commonsense views of the literary, and the expert reports from members of the boards (excerpts of which are sometimes included in the bibliography) were required to establish their own logic of what constitutes a literary work, drawing on their expertise (Cf. Darby, 32). In selecting titles to refer to the boards, Customs could both misrecognise books and assertively redefine their worth, as well as require the board to provide opinion on non-literary publications in order to establish broader practice.

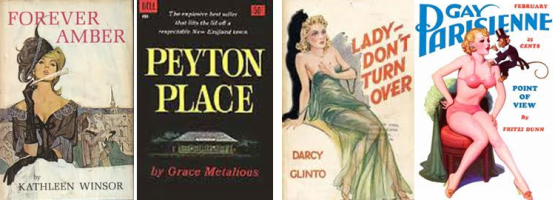

In addition to reviewing well-known literary titles like Alfred Doblin's Alexanderplatz: The Story of Franz Biberkopf and John O'Hara's Butterfield 8, and scholarly books on sexuality or pornography and censorship, such as Steven Marcus's seminal The Other Victorians, the board reviewed a significant number of popular fiction and pulp fiction titles (perhaps one-third of titles), and occasionally magazines and comics. Indeed a significant proportion of the dataset is devoted to popular fiction, most of which was authored by American writers. In 1967, the National Literature Board of Review was sent individual issues of Playboy for review, sparked by agitation from importers and distributors against its blanket prohibition by Customs. So while the dataset does include well-known as well as obscure or underground literary and scholarly works, it also includes publications with dubious literary merit, sent to the board to be assessed for exactly this characteristic, and banned because they lacked sufficient claim to the literary to excuse their obscenity. These titles include such best-sellers as Thorne Smith's Topper Takes A Trip, H. C. Asterley's Rowena Goes Too Far and Thom Keyes's All Night Stand.

The dataset includes scholarly publications, such as medical, sexology or anthropological scholarly studies, as well as literary titles. This is because these scholarly works were deemed to contain specialist knowledge that the literary boards were more qualified to assess than Customs officials. The dataset thus reflects the board's assessment of these titles too, including prohibited works such as John P. LeRoy's The Homosexual and His Society, J. P. De River's The Sexual Criminal: A Psychoanalytical Study, and Berlin psychologist Iwan Bloch's Anthropological Studies in the Strangest Sex Acts.

In keeping with the expansion of the notion of the literary, the category of a publication title has also been defined in very broad terms by the bibliography. While most of the titles included take the form of books, the literary censors were sometimes sent pamphlets, advertising brochures and other items of ephemera that clearly fall outside the category of a book title, narrowly defined. In particular, the boards were sent many underground French titles that resist easy categorisation. Pour Lire Au Lit is one of these publications sent to the board, possibly because of its obscure and foreign nature. This title is a small money order catalogue/pamphlet without conventional book publication details, such as author, publisher or publication date.

Publications like these have been difficult to trace and verify in international bibliographies, especially because they do not include publication details. In fact, 37 of the titles included in the bibliography are underground French publications. Some are works of erotic literature, dating from the seventeenth and eighteenth-century beginnings of modern pornography, such as the works of Restif de la Bretonne and the Marquis de Sade, but other erotic titles are works of antiquity, such as the Satyricon of Petronius or translations of the classic works of Arab and Indian erotica. German titles reflect Viennese and German interest in sexology and sexual psychology and taxonomy in the first half of the twentieth century. Some of the American titles included are mass-produced, pulp-fiction novels or American-published, faux-French books, trading on France's reputation by the early twentieth century as the biggest source of pornography for the English-speaking world.

While the bibliography typically treats each prohibited work as a separate and unique entry, there are some notable exceptions to this rule. If a publication is part of a broader series, the work is still provided with an individual record and a link is provided to the broader series. Alexander Trocchi's prohibited publication Young Adam is one example of a publication that exceeds narrow definitions of a single book title. It was prohibited on February 6, 1962 as a short story by Trocchi in an collection of his works titled The Outsiders, which was banned as obscene on the basis of the story. On the same date, its inclusion in The Seeds of Desire, a separate publication but the same collection re-titled, occasioned another ban. In addition to these two instances, it was also published as a stand-alone novel titled Young Adam, published under the pseudonym Frances Lengel, and this was banned on July 17, 1968. The diversity of its publication forms calls into question its very identity as a single title. Nevertheless, the censors have treated it as such and the AustLit data model, which draws together variant versions and publications of a single work, has allowed us to present the multiple manifestations in a single record which reflects the board's treatment of the title.

Most books included in the bibliography were prohibited on the grounds of obscenity or indecency, but the definition of obscenity was understood and interpreted in very diverse ways by the boards. The dataset reflects this diversity, including titles prohibited for including content as varied as swearing, divorce, birth control, abortion, incest, pedophilia, bestiality, polygamy, and explicit descriptions of heterosexual sex. It also includes titles prohibited for including violence, promiscuity, alcoholism, 60s free love and liberation, drugs, and anything from nudism and soft erotica through to variants of what is now and was then defined as hard-core pornography.

Furthermore, the bibliography does include some records for books that were banned for reasons other than obscenity. There are a few rare cases in which books were banned by a board on the grounds of blasphemy or sedition. The Book Censorship Board banned Mike Pell's book S. S. Utah on the grounds of sedition in April 1934 and Agnes Smedley's Short Stories from China in September 1935. (NAA A3023 Folder 1933/1934 Folder 1935/1936). Most books suspected of sedition were sent to the Attorney-General's Department for decisions after 1935, however, and these are not included in the bibliography (Watson, 69). Card indices document the many publications banned on political grounds through the 1930s, in a very active period determined by changes in the legislation and Customs regulations that affected international titles in particular (NAA Series C4127, NAA Series C4128). Joseph Lewis' The Bible Unmasked was banned by Customs as both obscene and blasphemous in 1929, inducing protests from Rationalists in Australia as well as an internal Customs officer, who noted that it consisted of a collection of quotations from the bible (NAA A425; 'Prohibited Publication 'The Bible Unmasked'; 1971/9600).

Australian authors

The dataset includes a small set of titles by Australian authors. These are almost all titles published in England or the US that were prohibited as imports despite their Australian origins. Banned books by Australians include Norman Lindsay's Redheap, Jean Devanny's books The Butcher's Shop and The Virtuous Courtesan, J. M. Harcourt's Upsurge, Frank Walford's Twisted Clay, Christina Stead's Letty Fox, Her Luck and E. L. Grant Watson's The Partners, published under the pseudonym John Lovegood. Titles by Frank Dalby Davison, Martin Boyd, Leonard Mann, Dal Stivens, Hal Porter and others were among the books considered by a board but passed for importation. Despite its obscenity conviction under Victorian law, the English edition of Robert Close's novel Love Me Sailor was passed by the Literature Censorship Board in 1951. The Minister exercised his power to overrule the Board, however, as Customs Ministers did on many occasions through the decades, and Close's book was kept out of Australia until 1960. The National Literature Board of Review ostensibly had powers to decide on domestic publications, under a uniform censorship agreement brokered between the states after 1967, but since powers to prosecute remained with the states, the Board did not exercise these powers in any meaningful way.

Information on the prohibition of titles has been sourced from a number of key file series of records compiled by Customs and held in the National Archives of Australia. One of the most useful series holds the records of literary censorship undertaken by the Literature Censorship Board through most of the years of its functioning, but concluding ten years prior to its transformation into the National Literature Board of Review. This series (NAA A3023 'Decisions, with Comments, on Literature Forwarded by the Customs Department to the Commonwealth Book Censorship Board, 1933-1957') is particularly useful because it contains a sequential collection of detailed reports from the members of the board on the censorship of books across twenty-four years.

These reports were assiduously collected, copied and preserved as a centralised record by Dr. Leslie Holdsworth Allen for the duration that he sat on the Book Censorship Board and Literature Censorship Board, and they are now digitised and available for viewing through the National Archives of Australia's database. The series provides detailed records of the titles of books that were sent to the board for review, as well as critical analyses of the books under consideration by the panel of three to four expert members and the Chairman of the Board. The reports detail the motivations underpinning every title's assessment, and whether the outcome was the book's prohibition, its restricted circulation, or its release for public circulation, including the date of the board's decision. The coherent body of records within this series provides a sustained picture of censorship practices in relation to literary titles between the 1930s and 1950s.

Sourcing decisions on titles was more difficult for the years following 1957, after Professor E. R. Bryan replaced Dr. Allen as Chairman. Professor Bryan's records are not as carefully maintained as Dr. Allen's, and we have had to look to other sources to document the evidence of book bannings from the late 1950s to the 1970s, to attain a more complete picture. The most useful series is a large and systematically-maintained card index contained within 26 boxes, providing records of all titles considered for prohibition by Customs officials from the early 1930s through to December 1973 (Series C4129/1 'Library index cards, alphabetical series'). It is an extraordinary record of department practice across many decades. The cards within this series are organised alphabetically according to book title, and each card provides clear indications of whether and when a publication was sent to a board for review, listing the dates the title was banned and sometimes released by a board.

Another card index contains similar information to C4129/1, except that the cards are organised alphabetically according to author rather than book title, and so they include more than one book title on each card. This series (C4130 'Author index cards to publications under review, alphabetical series') was generated much later than C4129/1, in 1958, rather than the 1930s, and so inclusion of information within this series about early book bannings is likely to be retrospective. Nevertheless, the two series together offer important confirmation of the information in each. At the same time, while the cards provide an extensive sweep of information over five decades, in comparison to the records from the Literature Censorship Board, they provide limited analyses of books, nor do they give the reasons for a book's prohibition. There is also some ambiguity about how reliable the card indices are as a record of the treatment of titles. Some instances of contradiction between the records of different series complicate our attempts to track individual titles through the hands of Customs officers and federal censorship agencies.

In addition to the C4129/1 card index, there are numerous other series that have furnished key information about censorship after the closure of the Literature Censorship Board in 1967. A series described as containing miscellaneous materials relating to the National Literature Board of Review includes detailed assessment reports on notable publications during the years that Professor Bryan chaired both the Literature Censorship Board and the National Literature Board of Review (Series C4371/1 'Folders of correspondence of the Chairman of the National Literature Board of Review'). This series provides dates for books that were prohibited by the boards in addition to critical assessments of prohibited books, although it is not comprehensive.

The series has also been very useful for furnishing the bibliography with the dates that publications were released from their prohibited and restricted status, because it tracks the National Literature Board of Review to its closure in 1973, and it details the review and release of previously banned books more fully than the banned publications. Furthermore, the series' documentation of the release of prohibited literary titles has also been enormously useful in providing us with missing information about some books banned before the establishment of the Book Censorship Board in 1933. In the process of listing literary titles for release, the National Literature Board of Review also provides a record of the date they were first banned, and it is in the recording of the book's first date of prohibition that we have also found dates for some literary titles that were banned before the establishment of the Book Censorship Board.

Nevertheless, some information is missing and the series is organised miscellaneously. Some of the gaps have been illuminated by other series such as a collection of book reports collated during the 1960s by the National Literature Board of Review. This series (C4226 'Case files of imported publication titles reviewed for release or prohibition, annual single number series') provides detailed case files of assessment reports on seventeen books assessed by the National Literature Board of Review between 1968 and 1972. The material in this series is useful in its detail and comprehensiveness, and for its insight into censorship policies and procedures endorsed through the 1960s. However, it is a small series and may not adequately reflect the breadth of book censorship during this period. We have also located a systematic card index of books banned after 1973 under the administration of the Attorney-General's Department after the closure of the National Literature Board of Review in 1973 (C3059/1 'Literature and miscellaneous records, classification'). Unlike the other card indices, this index provides no evidence that a special literary board of review assessed works of literary merit after 1973. With this in mind, we have not included literary books banned after 1973 by the Attorney-General's Department, since the procedures that had previously organised literary censorship no longer functioned in the same way.

Finally, we have generated information about literary books that were censored by Customs by conducting keyword searches on titles and authors within the enormous series collecting the correspondence of the whole Department of Trade and Customs (or Customs and Excise as it was known after 1957) (NAA A425 'Correspondence files, annual single number series'). Censorship records comprise only a very small part of the series and are collected as individual files under the titles of prohibited publications. We have located files on specific censored literary works using key information from other series, mostly the series generated by Professor Bryan (C4371/1). While this method involves attempts to predict what was prohibited, and so is also not comprehensive, it has allowed us to access many dense files on individual titles, which include such material as book reports and newspaper clippings.

Bibliographic research on each book title included in the bibliography has provided accurate and reliable information about the banned books and authors. The dataset usually only provides bibliographic details for the first prohibited edition of a banned book, but it does provide records for any further editions of a prohibited work if the board made alterations to the original banning decision by reviewing later editions. These bibliographic details have been checked against online library catalogues including WorldCat and Libraries Australia. In the instances where bibliographic details have not been traceable through these databases, we've checked the records against the bibliographic records kept by Customs themselves, as they administered the huge bulk of publications over the decades, or we have consulted authoritative online bibliographies about rare and/or cult prohibited books. There are a few cases in which the bibliographic details of a title, such as its publication date, publisher and author have not been verifiable. For example, there are a number of French underground publications from the early twentieth century that have not been verified, because of their underground, ephemeral status, remembering that in most countries prohibition of a title meant copyright could not be asserted (Cf. Saunders). In these instances, we've included records for these titles with a note explaining the omission of bibliographic details.

Based upon the information generated from the numerous series we've seen, we have been able to make new claims about the number of publications prohibited. In 1962, Peter Coleman's Obscenity, Blasphemy and Sedition influentially claimed that by 1936, 'including political publications and ephemeral novels', the banned list of prohibited publications numbered 5,000 (19). Many commentators have reproduced this estimate, which was based on Customs files provided to Coleman by then Minister Denham Henty (cf. Buckridge 174, Day 106). Stephen Payne has located Customs General Order 890 for March 1936, however, which lists only 513 prohibited titles. Payne contests Coleman's estimate as 'wildly inaccurate', noting also his report that in 1937 the number of political works banned for sedition was about 200, after which it declined (2). The General Order does not count 'ephemeral novels' or the great bulk of non-literary publications, however, and when these are included, our research suggests that a far greater number of publications than 5,000 were prohibited across the course of the twentieth century.

Our sources imply that approximately 16,000 titles of all genres, including pulp fiction, erotica, underground pornography, magazines, comics, art books and pamphlets, were banned by Customs between the early 1930s and early 1970s, and of these 16000 titles, at least 500 literary or scholarly books were banned or restricted by the literary boards between 1901 and 1973. The dataset's total of almost 500 prohibited literary titles is a conservative estimate because it excludes titles that may have been banned prior to the Book Censorship Board in 1933 which we have been unable to trace in the records. It also excludes titles not referred to a literary board but referred to the Director-General of Health or to the Attorney-General's Office for assessment on scholarly merit or sedition. There is also a small number of records that provide some evidence of the prohibition of further individual titles whose banning we have been unable to confirm. To date, there are approximately 30 records that fit this category. Of course, these figures are based upon the series that have been examined, and while these series do seem to cross-reference one another and confirm our information, it is still possible that records will be located that evidence further bannings.

The decision to place Banned in Australia as one of the research communities within Austlit: The Australian Literature Resource is a strategic one that allows us to challenge narrow definitions of 'Australian-ness' and 'literary culture'. The bibliography provides a unique picture of Australian literary culture as it is delineated by its negative engagement with 'outside' international literary production, since the majority of banned works included in the bibliography were written by international authors and published in international contexts. The bibliography works within Austlit precisely for this reason: it throws into relief the limits of Australian literary culture by highlighting the forms of international literary production that Australia refused to acknowledge. This, paradoxically, tells us a great deal about how literary culture was defined in Australia, and Austlit is an excellent platform to highlight the ways that Australian literary culture was formed through a process of exclusion.

There are 500 records listed in the 'Banned in Australia' subset that will be useful for a number of purposes. For the first time, members of the general public, scholars, students and authors, will be able to generate a list of every text banned and restricted between the years 1933-1973, or generate a list of titles banned in a specific time-frame, from the most-recently published to the oldest publication. We can search to see if a particular author or title has been banned or we can search for a prohibited publication according to a particular year, subject, work type, form or genre. This is a useful resource for anyone interested in Australian literary history and censorship, or histories of sexuality in Australia.

More than this, the bibliography allows for, even if merely retrospectively, the kind of civil right that Dutton and Harris claimed in 1970. Across the decades, we have the information to now assess the 'competence of the banners, the consistency of standards, the application or misapplication of laws' and to assess the worth and impact of those laws. It is not merely that we discover what we weren't allowed to read, but the frame through which Australians were forced to see themselves and the world around them comes into view.

WORKS CITED

Primary Sources

National Archives of Australia (NAA); Series A425; 'Correspondence files, annual single number series'.

—. (NAA); Series A425; Item 1943/5280 'Prohibited Publications 'L'Orgie Latine', 'Lulu'.'

—. (NAA); Series A3023; 'Decisions, with comments, on literature forwarded to the Customs Department to the Commonwealth Book Censorship Board, 1933-1957'.

—. (NAA); Series C4129/1; Index cards of publications under review, alphabetical series'.

—. (NAA); Series C4130; 'Author index cards to publications under review, alphabetical series'.

—. (NAA); Series C4371/1; 'Folders of correspondence of the Chairman of the National Literature Board of Review'.

—. (NAA); series C4226; 'Case files of imported publication titles reviewed for release and prohibition, annual single number series'.

—. (NAA); Series C3059/1; 'Literature and miscellaneous records, classification on censorship and legislation'.

—. (NAA) Series C4480; Item 23 'National Literature Board of Review Correspondence'.

—. (NAA) Series P437; 'Correspondence files, annual single number series' Item 1912/1710.

—. (NAA) Series P437; 'Correspondence files, annual single number series' Item 1922/678.

—. (NAA) Series 981/4; LEAGUE OBS 3 'League of Nations. International Agreement for the Suppression of Obscene Publications - Central Authority'.

Secondary Sources

A Chronicle of Freedom of Expression in Canada, http://www.efc.ca/pages/chronicle/chronicle.html (Accessed March 2008).

Bertrand, Ina. Film Censorship in Australia. St Lucia: U of Queensland P, 1978.

Buckridge, Patrick. 'Clearing a Space for Australian Literature, 1940-1965. ' Oxford Literary History of Australia. Ed. Bruce Bennett and Jennifer Strauss. Melbourne: Oxford UP, 1998. 169-192.

Coleman, Peter. Obscenity, Blasphemy and Sedition: The Rise and Fall of Literary Censorship in Australia. [1962] Sydney: Duffy and Snellgrove, 2000.

—. 'Letter to the editor.' Sydney Morning Herald, 20 September 1957.

Commonwealth Gazette 23, 24 April (1958): 1232-33.

Darby, Robert. 'The Censors as Literary Critics.' Westerly 4 Dec. (1986): 30-39.

Day, David. Contraband and Controversy: The Customs History of Australia from 1901. Canberra: AGPS, 1996.

'"Decameron" Banned": New Edition Withheld.' Argus 29 May, 1930, 9.

Douglas, Roger. 'Saving Australia from Sedition: Customs, The Attorney-General's Department and the Administration of Peacetime Censorship.'Federal Law Review 30.1 (2002): 135-175.

Dutton, Geoffrey, and Max Harris, eds. Australia's Censorship Crisis. Melbourne: Sun Books, 1970.

Jacobsen's Index of Objectionable Literature (1996), Housed by the Beacon for Freedom of Expression http://www.beaconforfreedom.org/.

Heath, Deana. 'Literary Censorship, Imperialism and the White Australia Policy.' A History of the Book in Australia. 1891-1945: A National Culture in a Colonised Market. Ed. Martyn Lyons and John Arnold. St. Lucia: U of Queensland P, 2001. 69-82.

—. 'Creating the Moral Colonial Subject: Censorship in India and Australia, 1880-1939.' PhD Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 2003.

Lyons, Martyn, and John Arnold, eds. A History of the Book in Australia 1891-1945: A National Culture in A Colonised Market, St Lucia: U of Queensland P, 2001.

Moore, Nicole. 'National Parapraxis: Memory and Forgetting in Australian Censorship History.' Australian Historical Studies. Special Issue: History of Sexuality in Australia 36.126 (2005): 296-314.

Office of Film and Literature Classification. Website. 'History of Classification.' http://www.oflc.gov.au/special.html?n=256&P=77

Payne, Stephen. 'Aspects of Commonwealth Literary Censorship in Australia, 1929-1941.' MA Thesis, Australian National University, 1980.

Saunders, David. 'Copyright, Obscenity and Literary History.' English Literary History 57 (1990): 431-444.

Watson, Don. Brian Fitzpatrick: A Radical Life. Sydney: Hale and Iremonger, 1979.

White, Thomas. Australian Parliamentary Debates No. 146, 354.

You might be interested in...